Tax hikes, according to IMF research praised by Paul Krugman.

The surprising thing is this is an IMF study that usually gets cited to show that spending cuts don’t grow the economy—that “expansionary austerity” is a mere theorist’s dream. But this

same research also provides evidence that tax hikes cause more trouble than spending cuts in the short run.

Quick summary of the method: The economists looked at 173 “fiscal consolidations” in rich countries, times when governments decided to reduce the long-run deficit. They then checked to see whether consolidations based mostly on tax hikes turned out better or worse than ones based on spending cuts (

Inside baseball: They followed a version of the

Romer and Romer event study methodology, but applied it to exogenous-looking fiscal tightening instead of exogenous-looking monetary tightening).

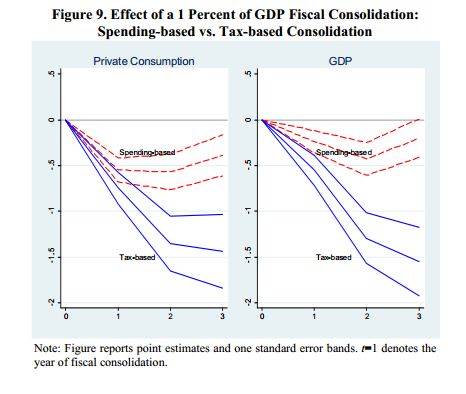

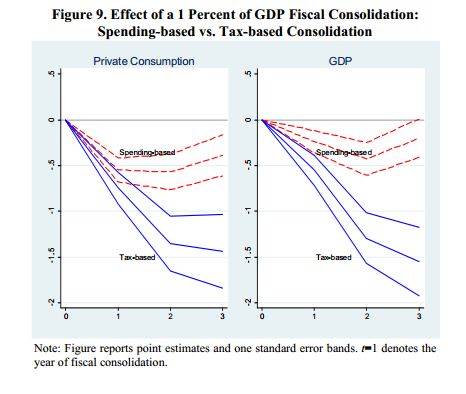

Here’s my favorite graph, one that I think smart people keeping drawing the wrong lesson from if they notice it at all. It shows what happens to consumer spending and real output after the two different kinds of fiscal tightenings. Time in years on the x-axis, percentage changes in spending on the y-axis:

Both GDP and consumer spending tell the same story: Spending cuts are the less painful path to fiscal rectitude. When countries tried to get right with the bond markets, this IMF study found that nations that mostly raised taxes suffered about twice as much as nations that mostly cut spending.

The authors give a possible (I said

possible) explanation of the results: Central banks play nice when governments cut spending, loosening up monetary policy. They’re not as nice when governments raise taxes. I’m sure somebody out there will say that the Federal Reserve and the ECB have run out of ammo so we can ignore Figure 9. To those people I say QE3 and

sovereign bond purchases. Central banks still do stuff and they do more when things look bad: In 2012, you can just read the newspaper and you’ll see.

Plus, possible.

We might want to meditate on Figure 9 out here in the reality-based community, since both the U.S. and Europe will be spending some time this fall wrestling with how to get our fiscal houses in order. A benevolent social planner would like to take the least-cost path to solvency, a path probably based on spending cuts and loose money.

Keynesian Coda: Notice that the graphs are saying that the tax multiplier is

bigger than the spending multiplier, at least in these settings. Quite the opposite of undergraduate Keynesianism. This isn’t the final word on the matter, but if you’d like to see another study of multipliers that doesn’t fit neatly into the Keynesian box–and written by top New Keynesians–check out the abstract and conclusion of

this paper by Blanchard and Perotti.

READER COMMENTS

Chris H

Nov 15 2012 at 12:18am

So someone who knows more about economics tell me if I’m completely off base here, but couldn’t the reason spending cuts aren’t as bad as tax increases simply be because when you cut spending, resources are freed to re-enter the private sector for usage there while tax increases takes away productive resources to go to the public sector?

Given the nature of the vast majority of government tax revenues, significant tax increases must come from currently productive resources not idle ones. Idle resources (including idle labor) have low to no consumption and produce no income and so contribute little to nothing to income taxes(including corporate and invested income) and consumption taxes. Therefore the taxes act as a discouragement on active resources while leaving idle resources untouched. Government will almost certainly not use those resources as effectively as the private sector and therefore the taxation is a definitive drain.

Reducing spending however draws resources away from less productive uses and gives the possibility that part or all of those resources will be directed to more efficient private uses. Those that aren’t used for that, some of those resources might have been used for purposes which are on net destructive uses that actually net decrease wealth (many military uses come to mind). Other idle resources from government usage might have been net gains on the economy from idleness, but most of those uses are unlikely to be as effectively utilized as private sector resources, so the loss there is less than a corresponding loss in the private sector.

Central bank actions might exacerbate the above effects if they occur as the IMF predicts, but that would seem to be secondary to the primary effect of higher taxes=resources taken from efficient producers and spending cuts=resources taken from inefficient producers.

Salim

Nov 15 2012 at 8:28am

Alesina, Favero, & Giavazzi look at the same question and get the same result. But they went a little further, and examined central bank responses. However, they didn’t find any evidence that central bank action is driving any of the difference between tax-based and spending-based responses.

Ken B

Nov 15 2012 at 9:31am

This makes intuitive sense to me in the following way. Government spending is pretty high. Even if you assume such spending is a good thing we are surely past the point of diminishing returns. However private spending is based on better information and incentives. It is more likely to be high-value.

Does this make sense of is it some sort of vulgar non-Keyensianism?

Daniel J. Artz

Nov 15 2012 at 10:21am

One possible, and I think highly likely, explanation for why the tax multiplier is higher than the spending multiplier is the difference between the efficiency of private spending vs. government spending. At high levels of government spending, the spending by the government suffers from low efficiency. High levels of fraud and waste, political interference in spending decisions, politically motivated spending decisions, all lead to high cost-benefit ratios for government programs; i.e., government must spend much more to obtain the same level of economic benefit than is the case when spending is subject to the discipline that market forces impose. Thus, for every dollar of government spending replaced by private spending, economic benefits increase. Conversely, for every dollar of private spending displaced by higher taxes, average efficiency of spending declines.

vasja

Nov 15 2012 at 11:24am

I didn’t have time to inform myself on the methodology so I’ll just post the question here. Did the regression control for the initial debt position? Majority of the countries that decided for raising taxes were the ones that were the most vulnerable during the crisis, had the highest GDP drop and debt/GDP ratio(no?). The reason is that this is the fastest way to raise revenue, as opposed to spending cuts that take time because of procedural reasons and blockages by different interest groups.

TBrynteson

Nov 15 2012 at 6:10pm

Has any of this analysis controlled for the amount of a tax hike from what sort of baseline? In essence, are we talking small, but widespread hikes across all income categories? Hikes only hitting, upper, or lowe, or middle class incomes? Hikes on capital gains or income? There are all kinds of variables in terms of what kind of taxes, on what level of income and the scale of the increase from the baseline. These kinds of analysis comparing “spending” with “taxing” don’t seem very helpful without more information.

Mike Rulle

Nov 15 2012 at 6:55pm

Everything old is new again. How often do we have to make this point since Adam Smith?

East Germany vs West Germany

N.Korea vs S. Korea

Taiwan/HK vs Communist China

USA vs USSR

Does anyone have a “jump theory” in economics proposing that only at the extremes does government spending and/or “investment”, directly or indirectly, perform worse than private sector spending and investment?

It is unbearable that we must resort to quoting Romer and Romer studies after Ms.Romer supported Zandi’s 1.72341736 stimulus multiplier. Who cares that her 20 year old study supports lower taxes over Govt. spending when coming out of recessions? What was her point in 2009? She gave some bastardized inverted version of Bastiat’s “what is not seen” to justify the stimulus package when criticizing Barro’s Korean War study.

Look up her speech.

Chris Koresko

Nov 17 2012 at 10:30am

Another point: Doesn’t the definition of GDP include government spending as an additive term? If so, it seems to me that reducing G by 1% of GDP must directly lower GDP by 1%, correct? If GDP actually drops by only 0.5%, then the private part of the GDP must grow by 0.5%.

If you assume that the benefit to society (in some admittedly ill-defined sense) of $1 of government spending is half the benefit of $1 of private spending, then the cut in G produces no net loss at all.

Or am I confused here?

Comments are closed.