Here is the mainstream media:

WASHINGTON (AP) — This isn’t explained in Econ 101.

Month after month, U.S. hiring keeps rising, and unemployment keeps falling. Eventually, pay and inflation are supposed to start surging in response.

They’re not happening.

Last month, employers added a healthy 252,000 jobs — ending the best year of hiring since 1999 — and the unemployment rate sank to 5.6 percent from 5.8 percent. Yet inflation isn’t managing to reach even the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target rate. And paychecks are barely budging. In December, average hourly pay actually fell.

Economists are struggling to explain the phenomenon.

“I can’t find a plausible empirical or theoretical explanation for why hourly wages would drop when for nine months we’ve been adding jobs at a robust pace,” said Patrick O’Keefe, chief economist at consulting firm CohnReznick.

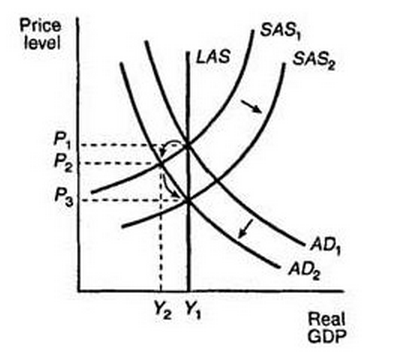

Perhaps those “struggling economists” should take an intro to macro course, where they might come across this graph:

The severe negative demand shock of 2009 put us at P2. Then wage growth moderates and we are currently moving between P2 and P3. That’s EC101.

Now obviously you wouldn’t have so many people confused if this occurred every single business cycle. In the past the Fed has often adopted expansionary monetary policies during recoveries. Then the adjustment burden does not entirely fall on lower wages, rather both AS and AD shift to the right. In that case wage growth often accelerates. But this time the Fed only allowed 4% to 4.5% NGDP growth during the expansion, which is actually less than the long-term average growth of both expansions and recessions. That’s a startling level of restraint. So the full burden of adjustment has fallen on aggregate supply. But the key point is this—given the low rate of NGDP growth, we are seeing an almost perfect example of the “self-correcting mechanism” after a fall in AD, right out of EC101 textbooks.

PS. I cheated a bit here because these EC101 graphs tend to deal with levels, and I am following the more modern practice of looking at rates of change. In level terms AD has grown, but because it’s grown less that normal, less than expected, it shows up as a negative AD shock. That partly explains the unusually slow recovery. You’d get the same general result with a more realistic dynamic model.

READER COMMENTS

TravisV

Jan 11 2015 at 2:13pm

Excellent graph! Here’s how I think of it:

If you have slack in the labor market and 3% nominal GDP growth, then wages will grow slower than other prices. For businesses, that means revenues (more tied to other prices) are growing faster than expenses (tied to wages). Since firms expect higher margins (revenues minus expenses), they hire more people in order to expand production.

What minimal rate of NGDP growth is needed to keep this process going? I’m not sure…..

Roger McKinney

Jan 11 2015 at 5:41pm

But that’s not an explanation; it’s just a description of what happened. Why has aggregate demand not grown?

Your answer is “he Fed only allowed 4% to 4.5% NGDP,” but that’s not accurate because the Fed never tried to slow ngdp growth. The whole point of zero interest rates and QE to infinity and beyond was to get higher ngdp growth. It failed.

Of course, like Keynesians you can claim that the Fed could have done more, but there is no way you can know that. You can only claim that your untested theory insists it must be true.

Roger McKinney

Jan 11 2015 at 5:46pm

But that’s not an explanation; it’s just a description of what happened. Why has aggregate demand not grown?

Your answer is “he Fed only allowed 4% to 4.5% NGDP,” but that’s not accurate because the Fed never tried to slow ngdp growth. The whole point of zero interest rates and QE to infinity and beyond was to get higher ngdp growth. It failed.

Of course, like Keynesians you can claim that the Fed could have done more, but there is no way you can know that. You can only claim that your untested theory insists it must be true.

PS, what most macro economists hide from their students is that aggregate demand is composed of consumer spending and investment. They ignore investment because they claim it is a very small part of AD.

They have GDP calculations to prove their point. But GDP is a highly stylized number and leaves out about half the economy. It counts only value added new production, which skews the data in favor of consumption.

The truth is that wages grow as a result of growing investment. But investment has been weak due to high taxes, regulation and regime uncertainty.

Lorenzo from Oz

Jan 11 2015 at 6:26pm

Roger. But it is not untested. See the example of Australia and Israel.

Future income expectations probably matter for investment too.

Scott Sumner

Jan 11 2015 at 7:19pm

Travis, As long as NGDP growth continues at 3.5% or more the economy will keep recovering–but growth should have been much faster since 2009.

Roger, Lots of misconceptions there:

1. Whether the Fed could or could not have done more has no bearing on my post, which was about the AS/AD model.

2. Bernanke always insisted the Fed could have done more monetary stimulus, it simply choose not to. In 2014 they tapered because they felt growth was adequate. Soon they will raise interest rates for the same reason. They did more than the ECB, and got more growth.

3. Of all economists, Keynesians are the most likely to claim the Fed could not have “done more.”

4. I doubt even 1% of macroeconomists hide from their students that AD contains C and I.

You said:

“The whole point of zero interest rates and QE to infinity and beyond was to get higher ngdp growth.”

Low interest rates do not represent easy money, they are a sign that money has been tight in the past. Bernanke, Mishkin, Friedman and many other leading monetary economists say low interest rates do not mean easy money. Herbert Hoover did QE–no one thinks Herbert Hoover had an easy money policy.

You said:

“They have GDP calculations to prove their point. But GDP is a highly stylized number and leaves out about half the economy. It counts only value added new production, which skews the data in favor of consumption.”

This is factually incorrect. GDP calculations include both consumption and investment, as well as G and NX.

Levi Russell

Jan 11 2015 at 8:33pm

So does everyone ignore the labor force participation rate when talking about recovery now or is that just a mainstream media thing?

Scott responds to Roger:

“Low interest rates do not represent easy money, they are a sign that money has been tight in the past.”

Yes, low inflation can lead to low interest rates. However, loanable funds theory suggests that, ceteris paribus, an increase in the supply of money (injected through credit markets) leads to a decrease in interest rates.

“This is factually incorrect. GDP calculations include both consumption and investment, as well as G and NX.”

Obviously I don’t know, but I’d wager Roger’s point is that GDP paints an incomplete picture of investment. Gross output statistics recently released by the BLS give a much more complete picture of investment than GDP does.

Roger McKinney

Jan 11 2015 at 9:10pm

That’s typical circular reasoning; assuming your conclusion.

I wrote that it does. But as the many criticisms of GDP calculations in both textbooks and on blogs show, it skews the data in favor of consumption. Common sense should tell people that no one can consume more than they produce, yet GDP accounting says we do. GDP accounting doesn’t account for half the economy, as the Gross Output data shows.

“Bernanke always insisted the Fed could have done more monetary stimulus, it simply choose not to.”

But he also said they didn’t do more because they didn’t think it would have any good effect but a lot of bad effects. They did not say that they would only allow 4% to 4.5% NGDP growth.

“They did more than the ECB, and got more growth.”

Again, the post hoc fallacy, the favorite of mainstream economists.

Scott Sumner

Jan 11 2015 at 11:02pm

Levi, I have a post on the LFPR over at themoneyillusion.

You said:

“Yes, low inflation can lead to low interest rates. However, loanable funds theory suggests that, ceteris paribus, an increase in the supply of money (injected through credit markets) leads to a decrease in interest rates.”

Yes, but the reverse is not true, low rates don’t imply easy money. I’d guess 90% of rate changes reflect other forces like slowing growth and lower inflation. And those can be caused by tight money.

Gross output double counts intermediate goods—what’s the point of double counting the same output?

Roger, You said:

“Common sense should tell people that no one can consume more than they produce, yet GDP accounting says we do.”

False. Babies consume more than they produce. And they are “someone.” Seriously, you may have some point here, but I have no idea what it is.

And when I name three famous monetary economists in support of my argument, and you respond “that’s circular reasoning” without explaining why, then let’s just say you have not convinced me.

Ray Lopez

Jan 11 2015 at 11:24pm

Professor Sumner: I was wondering how your graph today relates to “short-run” and “long-run” aggregate supply and demand, see more here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/AD%E2%80%93AS_model Does your model allow for the long run in aggregate supply and demand?

Levi Russell

Jan 11 2015 at 11:24pm

Scott,

So if we observe large monetary injections into credit markets and then see rates fall, we aren’t allowed to draw any conclusions? You guess 90% of rate changes reflect other things, but causality is tricky to establish when you don’t observe counterfactuals.

“Gross output double counts intermediate goods what’s the point of double counting the same output?”

So you have some idea what’s happening with intermediate goods! Are those markets not important?

Rodrigo

Jan 11 2015 at 11:54pm

Roger,

I am 25 and not an expert on monetary economics but even I know that when professor Sumner uses the phrase:

“Low interest rates do not represent easy money, they are a sign that money has been tight in the past.”

He is making a reference to Milton Friedman, who coined the phrase regarding the Japanese economy many years ago.

A

Jan 12 2015 at 1:28am

Roger McKinney, there are pretty good arguments available that the Fed reaction is asymmetric above and below 2%, and that the 2% market is closer to a ceiling, than a central tendency.

Look at Fed watcher Tim Duy’s posts to that effect, wherein he infers a return to the asymmetric reaction from the removal of the Evans rule:

http://economistsview.typepad.com/timduy/2014/03/kocherlakotas-dissent.html

http://economistsview.typepad.com/timduy/2014/03/unintentionally-hawkish.html

Likewise, David Beckworth examines the Fed’s own forecasts:

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2014/03/what-is-feds-real-inflation-target.html

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2014/12/tinkering-on-margins.html

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com/2014/12/the-federal-reserves-dirty-little-secret.html

Janet Yellen recently responded to a question about a slight dip below NAIRU by assuring “But it’s important to point out that the Committee is not anticipating an overshoot of its 2 percent inflation objective.”

Of course, the Fed doesn’t use NGDP as a target, but they do seem to go out of their way to paint 2% PCE as an upper boundary despite modest RGDP growth following a deep recession.

Scott Sumner

Jan 12 2015 at 10:03am

Ray, P2 is the short run equilibrium and P3 is the long run equilibrium.

Levi, I agree that there is a tremendous identification problem in monetary economics. But we do know that the vast majority of the time faster money growth is associated with higher interest rates. Money growth sped up sharply in the 1960s-1980s period, and interest rates rose. Latin America provides another excellent example. What tends to happen is that a monetary injection temporarily lowers short term rates in the short run, but not the long run. On the other hand monetary injections can actually raise longer term rates immediately. Look at the impact of the January 2001 or September 2007 policy “easing” on long term rates—in both cases long term bond yields rose on the day of the announcement. Transitory movements in short term rates (the so-called “liquidity effect”) have little impact on the macroeconomy.

Regarding intermediate goods, yes those markets may be important, but important for what purpose? The transactions costs in intermediate goods become a part of GDP. What else about them is important?

Levi Russell

Jan 12 2015 at 1:08pm

Well M2 growth has been pretty brisk since the mid-1990s but rates have fallen consistently since the 1980s. There are many factors at work here, but I don’t see it as cut and dried as “more money growth -> higher rates.”

Ray Lopez

Jan 12 2015 at 9:31pm

The Keynesian AS-AD model does not have a long-run aggregate supply, so obviously this is not a Keynesian model. With Keynes, shifts in short term AS, AD can cause a permanent change in output. I suppose that is a deliberate choice?

John Becker

Jan 13 2015 at 10:42am

I think you and the commenter are talking past each other on GDP. GDP skews towards consumption over investment because it avoids taking into account all the capital investments taking place along the chain of production in order to avoid double counting. I understand why they do this, but it leads people to think that consumption drives the economy. In truth without businesses plowing money back into their businesses (most of the total spending in the economy), we would slowly lose our ability to produce anything.

Scott Sumner

Jan 13 2015 at 11:20am

Levi, I agree that the correlation is far from perfect.

Ray, There are different versions of the Keynesian model. As you say, some old Keynesian models have no LRAS.

John, Investments made along the production chain do count toward GDP.

ThomasH

Jan 13 2015 at 7:50pm

Maybe the media should talk to real economists when trying to explain something. A real economist would have said that ceteris paribus that greated aggregate demand that led to higher employment would lead to higher wages. H might even have drawn an upward sloping supply of labor curve for the media person.

Comments are closed.