Last year I did a number of blog posts criticizing the consensus view that Japan had fallen into a recession. Many people assumed that two consecutive declines in real GDP meant that Japan was in recession. I argued that the two consecutive quarter criterion was not reliable, for instance RGDP did not fall for two consecutive quarters in the 2001 recession in the US. The NBER is considered the official arbiter of business cycle dating in the US, and they look at a wide range of indicators.

In the US, unemployment always rises sharply during recessions, and I believe that’s the stylized fact that people should focus on. Obviously people are free to define recessions as they wish, but our models of recession are typically aimed at explaining big increases in involuntary unemployment.

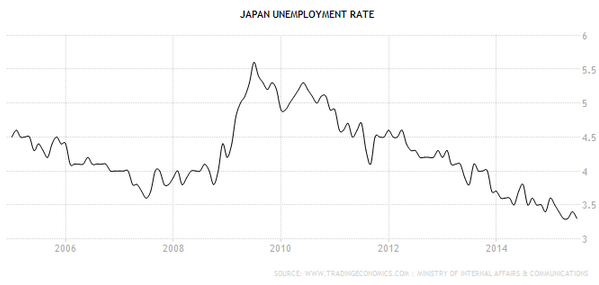

At the time, some commenters suggested that unemployment was a lagging indicator, and that my claim of no Japanese recession was premature. Here’s the Japanese unemployment rate over the past 10 years.

As you can see, unemployment does increase in an actual recession like 2008-09. However in the three subsequent pseudo-recessions the rate of unemployment did not increase. In the most recent case, Japanese consumers bought lots of goods right before the April 1, 2014 sales tax increase, and GDP fell immediately afterwards. Firms didn’t lay off workers, knowing that it was simply a timing issue, not an actual recession. Massive natural disasters like the 2011 tsunami also don’t impact unemployment in a big, diversified economy.

Today one can find many news reports that Canada has fallen into recession. My prediction is that a year from today we’ll know that this was also a pseudo-recession. Unlike in 2008-09, Canada will not see a significant rise in its unemployment rate (which has been stuck at 6.8% for the past 6 months.)

Canada’s RGDP fell due to a weak commodity sector. However commodities are land and capital intensive, not labor intensive. So relatively few jobs are lost when commodities decline. Even Texas is still gaining jobs. The fall in Canada’s real GDP is an optimal response to the negative commodity shock, and should not be addressed with monetary policy. Indeed in the past I’ve suggested that major commodity exporters should target something like total labor compensation, or average wage rate, rather than NGDP.

For big diversified economies like the US and China, it probably doesn’t matter. In those two cases a significant fall in RGDP would probably represent a recession (indeed even a small increase in RGDP in China might be viewed as a recession.)

To summarize, don’t obsess about words such as “recession”. Words can get in the way of meaning. The concept we are interested in is a general fall in economic activity across a wide range of industries, leading to a big rise in unemployment. Between January 2006 and April 2008 we saw US housing construction fall in half. But that was not an economy-wide phenomenon; it simply represented the after-effects of misallocation of resources into housing (or at least misallocation is the standard view, Kevin Erdmann would argue otherwise.) But regardless of what caused the housing slump, unemployment merely rose from 4.7% to 5.0% over 27 months. That’s not significant, as recessions in the US are caused by monetary shocks that reduce NGDP, not reallocation of resources. When actual recessions occur, unemployment rises by at least 200 basis points

PS. If you don’t accept my definition of recession, then call a generalized fall in business activity a “banana”. Then my claim is that tight money causes bananas. (Does anyone recall where I got the term ‘banana‘?)

READER COMMENTS

TallDave

Sep 1 2015 at 2:47pm

Starting to suspect production is more important that employment, such that the traditional definition of recession as two consecutive quarters of falling RGDP might be superior.

Of course, given that (as during WW II) utility can fall even as production rises, we really need to start calculating GDU. Prepare the brain probes!

Scott Sumner

Sep 1 2015 at 3:36pm

TallDave, I must strongly disagree. The sort of fall in production recently experienced by Japan and Canada is a trivial problem. A big rise in unemployment is a devastating problem. There is no comparison, in a business cycle context. Of course for long run economic growth, exactly the opposite is true.

marcus nunes

Sep 1 2015 at 5:07pm

Scott, dont forget to add Australia to the recession candidates roll!

http://www.wsj.com/articles/is-australia-sliding-into-recession-1441091988

TallDave

Sep 1 2015 at 10:40pm

Scott — Would agree with that in the US economy of 30 years ago and even more so 70 years ago, but leisure, welfare, and utility are so much higher today that the availability of employment seems relatively less important to overall living standards than the continued increase in our awe-inspiring ability to produce stuff people want. The utility tradeoff is (of course) difficult to quantify but is evidenced by the relative numbers of people who choose leisure over work (particularly difficult work) as the consumption floor rises over time.

I suspect the brain probes will support my hypothesis, and I think we can all agree dissecting a few thousand randomly sampled brains each year is a small price to pay to answer this important question.

ThomasH

Sep 2 2015 at 10:01am

Doesn’t that depend on whether the the monetary policy was optimal or not and the shock was of the nature that the policy was optimized for?

If BoC were targeting NGDPL it will raise the price level to offset the decline in real GDP. The higher inflation allow prices of un-shocked tradeables to rise (with the depreciation of the exchange rate) without the prices of non-tradeables falling. This would look to the public like “monetary policy” as it bought short and or long-term financial assets, lowered IOR, etc. — whatever needed to raise inflation, but that would not be a departure from the existing rule, so in that sense it would not be “addressing” the real GDP fall.

A PL trend policy would not allow inflation to increase (if the starting point were on target) and so might not facilitate the needed adjustment in relative prices and so seems clearly sub-optimal.

A policy of targeting the price level trend of a basket of non-tradeables would produce more inflation than a NGDP policy but might be optimal if the needed change in relative prices is large.

Benjamin Cole

Sep 2 2015 at 10:05am

“Banana” I think goes back to the Carter days, and that guy who deregulated the airlines. I did not cheat on this answer. Kahn, wasn’t it?

Okay, now I cheated and went to Google. Alfred Kahn.

History is funny. Nixon had wage and price controls, and gimmicked with milk-price supports. Nixon is on tape telling Burns to get the economy going.

Carter deregged airlines, trucks (I think railroads too), finance, telecoms. Not sure about energy. Carter appointed Volcker. After the 1975-6 recession, the GDP grew real by 20% in four years (Carter years).

Reagan is known as the great inflation fighter–left office with the CPI at 4.4%, went to 4.6% in 1989. Reagan left office with “rising inflation.”

Obama may leave office with inflation at 0%. Sinking inflation at that.

And Obama spends double, in real terms, what Reagan spent on national defense.

Kahn was a great guy, spoke his mind.

But history is funny.

James Hartwick

Sep 2 2015 at 5:02pm

I didn’t know the banana reference, so I followed Scott’s link to the wikipedia page about Kahn. I found the paragraph below:

And to think I bought into the popular fiction that it was the Republicans who were the deregulators.

Lorenzo from Oz

Sep 2 2015 at 5:48pm

Banana — Build Absolutely Nothing Anywhere Near Anyone. The Californian upgrade of Nimby — Not In My Back Yard.

But I suspect that is not the use of banana you mean 🙂

Willy2

Sep 5 2015 at 1:01pm

– Japan has A LOT OF hidden unemplyment.

Willy2

Sep 6 2015 at 5:23am

What happens to the canadian debt growth ? Is debt growth accelerating, flat or falling ?

Think Steve Keen: GDP = Income + change in debt.

Comments are closed.