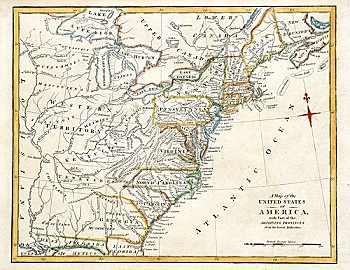

One of the most surprising parts of Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations is his Chapter Seven of Book Four, titled “Of Colonies.”In it, Smith discusses the effects of colonization by governments in Europe. Of particular interest is Smith’s discussion of the effects of the British government’s treatment of the thirteen colonies in North America.It’s all there. Smith did a cost/benefit analysis, with actual numbers, of Britain’s policy of maintaining the colonies, in which he totaled up the costs to Britain and estimated that these were well above the benefits. He then gave a simple explanation, by way of an analogy with shopkeepers, for why the British policy persisted despite the unfavorable cost/benefit ratio. Smith then advised the British government to give up its colonies and predicted that it would not do so without being defeated in war. As a bonus, he predicted that the nation that would arise from those colonies would become the most powerful nation in the world. On top of all this, Smith made a terse but passionate defense of economic freedom.

These are the opening two paragraphs of David R. Henderson, “Adam Smith’s Economic Case Against Imperialism,” published by Liberty Fund on Adam Smith Works. The whole thing is worth reading. It contains some of my favorite quotes from Smith, some of which I always used my first day of class when teaching economics to persuade the students that people who reject Smith as “so 18th century” did not appreciate either Smith’s analytic ability or his predictive ability.

READER COMMENTS

Jon Murphy

Oct 26 2018 at 3:14pm

That is one of the most interesting chapters in WN. Combining that with his letter “On the American Contest” shows a very careful, and at times devious, Adam Smith.

nobody.really

Oct 26 2018 at 3:27pm

Congrats on the book!

Let he who professes to be unimpressed with Adam Smith read the following and then pronounce himself unmoved:

• [The] disposition to admire, and almost to worship, the rich and the powerful, and to despise, or, at least, to neglect persons of poor and mean condition [is] the great and most universal cause of the corruption of our moral sentiments.

• Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all.

• [I]n the mercantile system the interest of the consumer is almost constantly sacrificed to that of the producer….

• We rarely hear, it has been said, of the combinations of masters, though frequently of those of the workman. But whoever imagines, upon this account, that masters rarely combine, is as ignorant of the world as of the subject….

• People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public….

• Our merchants and master-manufacturers complain much of the bad effects of high wages in raising the price, and thereby lessening the sale of their goods both at home and abroad. They say nothing concerning the bad effects of high profits. They are silent with regard to the pernicious effects of their own gains. They complain only of those of other people.

• The liberal reward of labour, therefore, as it is the affect of increasing wealth, so it is the cause of increasing population. To complain of it, is to lament over the necessary effect and cause of the greatest public prosperity.

• No society can surely be flourishing and happy, of which the greater part of the members are poor and miserable. It is but equity, besides, that they who feed, cloath and lodge the whole body of the people, should have such a share of the produce of their own labour as to be themselves tolerably well fed, clothed, and lodged.

• [Government enterprises are justified when,] though they may be in the highest degree advantageous to a great society, are, however, of such a nature, that the profit could never repay the expense to any individual or small number of individuals.

• Let us suppose that the great empire of China, with all its myriads of inhabitants, was suddenly swallowed up by an earthquake, and let us consider how a man of humanity in Europe, who had no sort of connection with that part of the world, would be affected upon receiving intelligence of this dreadful calamity. He would, I imagine, first of all, express very strongly his sorrow for the misfortune of that unhappy people, he would make many melancholy reflections upon the precariousness of human life, and the vanity of all the labours of man, which could thus be annihilated in a moment. He would too, perhaps, if he was a man of speculation, enter into many reasonings concerning the effects which this disaster might produce upon the commerce of Europe, and the trade and business of the world in general. And when all this fine philosophy was over, when all these humane sentiments had been once fairly expressed, he would pursue his business or his pleasure, take his repose or his diversion, with the same ease and tranquility, as if no such accident had happened. The most frivolous disaster which could befall himself would occasion a more real disturbance. If he was to lose his little finger to-morrow, he would not sleep to-night; but, provided he never saw them, he will snore with the most profound security over the ruin of a hundred millions of his brethren, and the destruction of that immense multitude seems plainly an object less interesting to him, than this paltry misfortune of his own.

(Likewise, let he who regards Adam Smith an advocate of laissez-faire policies read the aforementioned quotes….)

Philo

Oct 26 2018 at 5:25pm

Advocating governmental provision of public goods is not normally considered opposition to laissez-faire.

Mark Z

Oct 26 2018 at 5:36pm

Only one of the quotes (two at most) could be said to have anything to do with state intervention in the economy, and even that’s possibly misinterpreting them. Regarding the first quote, ‘laissez faire’ advocates do not seek to limit the government to the protection of property, but of all individual rights, including the right to assembly. Number 9 is the only one suggesting the utility of government action.

By the standards of the modern state, Smith would be considered ‘laissez faire.’ He wasn’t a full on anarchist, true, but that’s a pretty low bar to set for such a standard. He certainly was no social democrat.

David Henderson

Oct 26 2018 at 6:13pm

Mark Z,

I think you mean the second quote. If so, good point.

Mark Z

Oct 27 2018 at 4:23pm

Oops, yep I did indeed, thanks!

Jon Murphy

Oct 26 2018 at 9:00pm

Why don’t we let Smith speak for himself?

Seems quite laissez-faire to me

David Henderson

Oct 26 2018 at 6:18pm

David Henderson

Oct 26 2018 at 6:21pm

I’ll also quote something else nobody.really quotes, his (or her) third quote:

A large part of his book Smith wrote to refute mercantilism and defend and free trade.

But folks, it would be better if we didn’t sucked in by nobody.really, even though I just did. Instead, it would be nice to discuss the original post.

Daniel Neylan

Oct 27 2018 at 4:21pm

Hi from Down Under (Sydney, 10 kilometres from Botany Bay, to be more exact!)

Colonisation and the corollary trade controls might be seen as a form of new intellectual property and patent, eventually leading to greater prosperity the world over? Smith’s points in and of themselves are of course prescient in most respects.

From Australia’s perspective as a penal colony, there were probably many different calculations than those across the Atlantic. Not sure how that business case would have stacked up in comparison, but on balance we are very thankful they made their decision! Arguably the indigenous people would be too, compared to the potential alternative colonisers!

I recommend The Fatal Shore for a blow by blow account of the pre and post First Fleet voyage, for those interested in a different colonisation case study!

Regards

Daniel

Weir

Oct 28 2018 at 7:26am

My short review of The Fatal Shore: Too much of the twice or thrice-convicted felon, “the chain, the scourge, and compulsory labour” (Godfrey Mundy). Not enough of his fellow-villager, “allowed to work for his own livelihood, in a cheap country, with a splendid climate, and at a rate of wages unheard of in England” (Mundy again).

Samuel Lazarus: “If a man cannot be content with getting money honestly in a country where industry finds so many openings to prosperity and often competence, he deserves a rigid punishment.”

Francis Adams: “Australia is the best place in the world (taking it all round) for the rank and file, and for the rank and file of art and letters no less than of trade and labour.”

Bridget Burke: “This is the finest country in the world for young people that takes care of themselves.”

Thomas Braim: “The convicts are allowed to choose their own masters, bargain for their own wages, and quit their service in a month if they dislike their situation, the Crown maintaining them while out of employment.”

I could happily keep going with a hundred of these. You won’t find any of it quoted in that book by Bob Hughes. It’s not like it’s a bad book.

A much better book is John Hirst’s Freedom On The Fatal Shore, which is two books in one. Or read any of the smaller books by the same historian. Not an art critic. Robert Hughes on Renaissance art? An excellent guide. But if you pick up a copy of his history of Rome, the first thing you do is you rip out all the ancient history and start a couple thousand years in.

John Hirst is the real deal. Whereas Hughes can’t see the jacarandas for the flame trees. He misses the big picture, which is that Australia wasn’t really a penal colony. The history of Australia is ridiculously interesting. Hughes didn’t know the half of it.

Francois Peron: “Never perhaps has a more worthy object of study been presented to a statesman or philosopher; never was the influence of social institutions proved in a manner more striking and honourable to the distant country in question.”

William Broughton: “To call forth the resources of a new country like this, it is plain that every man should be encouraged to exert his utmost skill and industry; which he will never do but in the hope of acquiring property. And if a prisoner is in a capacity to acquire property, he must from the force of circumstances be able, in proportion to his endowments of mind and body, to acquire it more easily than he could in England.”

Henry Kingsley: “What a happy exchange an English peasant makes when he leaves an old, well-ordered society, the ordinances of religion, the various give-and-take relations between rank and rank, which make up the sum of English life, for independence, godlessness, and rum!”

Daniel Neylan

Oct 30 2018 at 5:04pm

Yep and yep. Tyler Cowen might call it a big elephant! I’ll read your rec with interest. Bill Gammage’s Greatest Estate on Earth another good one

Daniel Neylan

Oct 30 2018 at 5:06pm

Yep and yep. Tyler Cowen might call it a big elephant! I’ll read your rec with interest. Bill Gammage’s Greatest Estate on Earth another good one

I’d add that Bob Hughes’ art metaphors in his general imagery of the times make for good entertainment.

Mark Z

Oct 27 2018 at 4:34pm

For the purpose of “steelmanning” the Marxian argument that capitalism inevitably leads to imperialism and the two are inextricably linked, one might argue that, even if Smith is right and a capitalist society does not, in net, benefit from imperialism, it does inevitably produce interests (like the shopkeepers’ lobby) that will successfully lobby for imperialist policies. So, the situation public choice theorists accurately describe is inevitable in a capitalist society, the argument might go.

Weir

Oct 28 2018 at 7:36am

This is from no less an eminence than Disraeli himself: “Those wretched colonies will all be independent in a few years, and are a millstone round our necks.”

Likewise Charles Dilke said in 1868 that “in war-time we defend ourselves; we defend the colonies only during peace.”

So when the Japanese took Singapore they rode in on bicycles.

Dilke: “In war-time they are ever left to shift for themselves, and they would undoubtedly be better fit to do so were they in the habit of maintaining their military establishments, in time of peace. The present system weakens us and them us, by taxes and by the withdrawal of our men and ships; the colonies, by preventing the development of that self-reliance which is requisite to form a nation’s greatness. The successful encountering of difficulties is the marking feature of the national character of the English, and we can hardly expect a nation which has never encountered any, or which has been content to see them met by others, ever to become great. In short, as matters now stand, the colonies are a source of military weakness to us, and our ‘protection’ of them is a source of danger to the colonists.”

Max Goedl

Nov 3 2018 at 8:57pm

Also worth mentioning: Smith’s argument that slaves are treated worse under (otherwise) free and democratic government than under arbitrary government:

“The law, so far as it gives some weak protection to the slave against the violence of his master, is likely to be better executed in a colony where the government is in a great measure arbitrary than in one where it is altogether free. In every country where the unfortunate law of slavery is established, the magistrate, when he protects the slave, intermeddles in some measure in the management of the private property of the master; and, in a free country, where the master is perhaps either a member of the colony assembly, or an elector of such a member, he dare not do this but with the greatest caution and circumspection. The respect which he is obliged to pay to the master renders it more difficult for him to protect the slave.”

Brock d’Avignon

Nov 7 2018 at 2:40pm

Any thoughts on David Graeber’s anthropological attack on the myth of barter, making the case for actual credit arrangements over millenniums, everywhere and everywhen. He begins his attack on most Econ textbooks by showing how Adam Smith used a thought experiment example and purported it to be based on North American Indian culture doing barter. Actual practice was a matriarchal maintained anarchies-communal common storehouse. Having dented Smith’s credibility there, Graeber attacks his utopian debt-free notions elsewhere. Free-marketeers should, whether referencing history or data, be honest.

Praxeology and empiricism, thinking and doing, need to both be done in Volitional Science to advance creativity for freedom, and see how the solution worked out after all.

Comments are closed.