Ken Duda directed me to a speech by Stanley Fischer, which lays out four options for the next time rates hit zero:

1. Negative interest on reserves

2. A higher inflation target

3. Fiscal stimulus

4. Abolition of currency

It’s disappointing to see no mention of the most powerful tool for addressing the zero bound, level targeting. That’s not just my view, but also the view of prominent New Keynesians like Michael Woodford. And it was also the view of Ben Bernanke back in June 2003. The following is from the transcript of one of Bernanke’s first FOMC meetings:

What I think has been missing from the discussion we have had here today so far is that working on expectations of future short-term interest rates can be done through a comprehensive package. There are many different ways to approach expectations management. One is communications of the type we’ve been doing through our statements. There are various targeting procedures for inflation or price level targeting. Eggertson and Woodford talk about some reasons for price level targeting, which is their favorite approach.

Lawrence Ball wrote a paper claiming that Bernanke’s views were immediately shot down at that meeting, and that after that time Bernanke switched to the Fed’s internal views of policy, which most certainly did not involve level targeting:

Sections IV-VI review the broader evolution of Bernanke’s views. I find that they changed abruptly in June 2003, while Bernanke was a Fed Governor. On June 24, the FOMC heard a briefing on policy at the zero bound prepared by the Board’s Division of Monetary Affairs and presented by its director, Vincent Reinhart. The policy options that Reinhart emphasized are close to those that the Fed has actually implemented since 2008; Reinhart either ignored or briefly dismissed the more aggressive policies that Bernanke had previously advocated.

In the discussion that followed the briefing, Bernanke joined other FOMC members in agreeing with most of Reinhart’s analysis.

So why is the Fed so opposed to level targeting, when outside economists (including me) find the idea so appealing? Perhaps because it would radically change the nature of monetary policy. The Fed talks a lot about “targeting” inflation, but it never really takes ownership for changes in the value of money. It makes gestures toward easier or tight money, but doesn’t commit to make up for any shortfalls over overshoots.

If you still have trouble seeing why the difference between growth rate and level targeting is so important, consider that under level targeting it would no longer make sense to think in terms of policy hawks and doves, as the long run rate of inflation (or NGDP growth) would not be affected by today’s decision. If a hawk succeeded in lowering inflation to 1% this year (under a 2% level target), then the Fed would have to shoot for 3% next year. In other words, the low inflation would be a Pyrrhic victory for policy hawks, and hence there’d be no point in being a hawk.

Now suppose the Fed doesn’t want to be forced to shoot for 3% inflation, whenever they undershot with 1%. Suppose they don’t want the press constantly pointing out that any gap between the actual price level and the target path is the Fed’s fault. Under growth rate targeting they can always point to temporary shocks, unexpected events. “It’s not our fault.” That won’t work under level targeting. Under level targeting, the Fed would have had to have been far more expansionary after 2008, and they apparently didn’t want to be far more expansionary.

Last time there was a big gap between central banks and leading theorists was during the 1920s, when the leading theorists favored price level targeting (or NGDP targeting in a few cases) and the central banks favored the gold standard. We now know that the leading theorists were correct. It will be interesting to see who ends up being right this time.

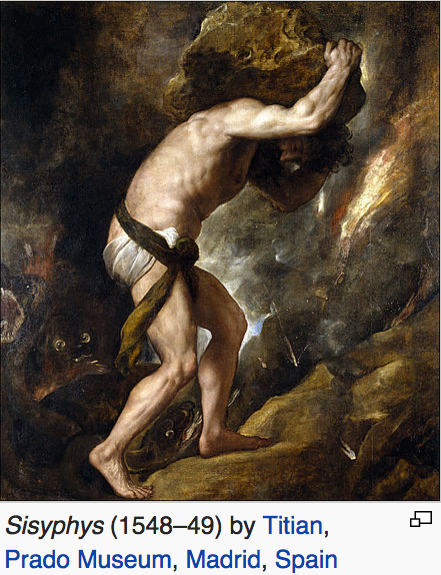

I wasn’t at the recent AEA meetings, but I’m told there was lots of discussion of how income inequality reduces aggregate demand. Combine that depressing tidbit with the fact that grad schools no longer teach macroeconomic history. Here’s macroeconomics, described by one of my favorite artists:

READER COMMENTS

marcus nunes

Jan 6 2016 at 2:10pm

Scott, Stan Fischer was always against NGDP level targeting. Ironically, he didn´t even notice that keeping NGDP on trend while BoI chief was what allowed Israel to avoid a recession in 2008/09!

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2014/04/25/sometimes-you-get-lucky-the-case-of-israel/

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Jan 6 2016 at 2:16pm

Do we really need level targeting if we had a credible, rules based, monetary authority?

Moreover, do we really need level targeting if we had functional NGDP futures market, and the monetary policy stance were defined based on this market ?

The reasoning behind my questions is that it seems to me that under a particularly severe negative supply shock, level targeting could lead to a few years of high inflation. If it´s all a credibility issue, maybe we have other ways to solve the expectations puzzle…

Don Geddis

Jan 6 2016 at 4:20pm

@Jose Romeu Robazzi: Level targeting only makes a difference, to the extent that the central bank makes errors. The scenario you’re talking about, where a negative supply shock forces the central bank to aim for high inflation, is a function of NGDP targeting, not a function of level targeting.

(There’s an argument that the high inflation is a smaller price to pay than a crash in trend NGDP, but that’s an argument for a different post. It’s not related to level targeting.)

Kevin Erdmann

Jan 6 2016 at 6:25pm

I apologize for making everything about housing, but after reading your last paragraph, I wrote this post today, in which I describe a link between income inequality and stagnation, through housing.

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Jan 6 2016 at 7:10pm

@Don Geddis

Even worse. Under a positive supply shock IT level targeting may cause excessive monetary stimuli and perhaps financial instability.

I think that IT has been compared unfavorably with NGDP targeting so many times that there was no point in applying LT to IT. But the question remains, nonetheless. LT is a tool to deal with credibility and expectations. If the economy has indeed at least in part long and variable LAGs, LT may become an additional problem, not a robust solution. Perhaps other ways to deal with credibility (i.e. a rules based monetary authority) may be a less radical and equally effective solution.

Don Geddis

Jan 6 2016 at 10:55pm

@Jose Romeu Robazzi: Level targeting is not just for gross short term errors. It also allows you to plan long term. If you and the bank agree on a 30-year mortgage, it would be nice to have some idea of the value of those dollars that you will repay three decades from now. Without level targeting, it’s not possible to run the economy precisely enough to have anything except huge error bars on the value of the currency many decades away.

That isn’t really about “credibility”. It’s about future predictability.

Jose Romeu Robazzi

Jan 7 2016 at 8:34am

@Don Geddis

I get all that, but what concerns me is that most demand management ideas, by construction, they assume supply side disturbances are minor. LT has a feature of trying to catch up some preordained idea of how the economy should behave, given minor supply side disturbances. But the real world shows us that supply shocks do occur, and sometimes they are huge even for the US economy. Therefore, LT has a potential downside as a demand management tool that should not be ignored. Also, it has been advocated that a demand management tool should target the forecast, of whatever nominal variable one chooses to target. Under LT, what should be the target ? all time level? 3-year level, 5-year level ? Prof. Sumner here has advocated periodic reviews of the target, should LT be adopted. To me it seems that this argument is an implicit recognition that one should not look at “all time” level in order to guide demand management policies. I think he is right, the world changes, and it is not always just demand.

Benjamin Cole

Jan 7 2016 at 8:57am

Great painting of Sisyphus by Titian. But incomplete in the modern context. Market Monetarists must also endure the

slings and arrows of the tight-money fanatics.

Rajat

Jan 7 2016 at 7:18pm

Scott, I can see the advantages of level targeting cited in your post, but I’m still confused as to how level targeting per se helps at the ZLB. For example, assume that the FFR is 1% and a negative demand shock pushes the Wicksellian interest rate down from 1% to -1%. The Fed reduces the FFR down to 0% and promises to keep it there until the price level returns to its former path. But if the market doesn’t expect the Wicksellian rate to ever rise above zero without an injection of cash, then how does level targeting help? I can see how it would help combined with QE or fiscal stimulus; I’m just not sure how it would on its own ensure the Wicksellian rate will rise above zero. Or is the point that level targeting would help avoid hitting the ZLB in the first place? Any concrete steppes for folk like me?

Don Geddis

Jan 8 2016 at 12:25am

@Rajat: “Targeting” (of levels, or anything else) is a tool of expectation management. But expectations have to be about something. In monetary policy, what they are, is about the path of the money supply. I.e., the concrete steps you’re looking for, are OMOs/QE. It wouldn’t make sense to try to propose level targeting, without also proposing regular Open Market Operations to adjust the money supply in order to meet those targets.

Once you know the “Chuck Norris concrete threat, then it turns out you rarely need to carry it out. The central bank merely announcing a level target, will cause velocity to change sufficiently in anticipation, that most of the work of getting to the NGDP target will happen without major money supply changes.

But you do always need the initial credible threat of money supply changes, in order to allow expectations to do the work.

Rajat

Jan 8 2016 at 3:51am

Thanks Don, that makes sense to me. I guess one could say the same thing about a higher inflation target – both level targeting and a higher inflation target need to be accompanied by the ability to change the money base (through OMOs/QE) to work. Whereas I presume that, say, negative interest on reserves would not require that?

Comments are closed.