Welcome to the fourth and final installment of the EconLog Reading Club on Ancestry and Long-Run Growth. This week’s paper: Chanda, Areendam, C. Cook, and Louis Putterman. “Persistence of Fortune: Accounting for Population Movements, There Was No Post-Columbian Reversal.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 6 (3): 1-28.

The authors data is here.

Summary

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (AJR) famously argued that the world’s former colonies have seen a great “reversal of fortune.” On average, the more advanced such countries were in 1500, the poorer they are today. In this week’s paper, Chanda, Cook, and Putterman (CCP) argue that AJR omitted a mighty confounding variable: ancestry. While nations‘ fortunes reversed to some extent, peoples‘ fortunes persisted. Countries inhabited by the descendants of relatively successful tribes in 1500 remain relatively successful today.

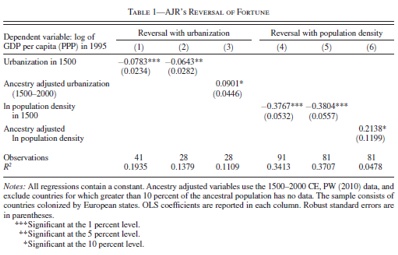

CCP begin by applying the Putterman-Weil World Migration Index to AJR’s measures of initial development: urbanization and population density. Ancestry adjustment easily re-reverses AJR’s reversal.

CCP then move on to a host of robustness checks. As usual, geographic controls dramatically cut the measured effect of ancestry. Results for urbanization and population density are fragile, but SAT scores are robust. I leave the multitude of other robustness checks to the reader; clearly the authors wanted to cover their bases.

“Persistence of Fortune” then argues AJR were too quick to claim victory for “institutions” over “human capital” stories of development. The big lesson:

We find no evidence of an important subset of national groups converting themselves from relatively “backward” to relatively “advanced” by adopting better institutions. The AJR (2002) reversal is instead associated with people from places hosting societies that were relatively socially and technologically sophisticated in 1500 migrating to places that had been relatively backward and that accordingly had relatively low population densities (which were further diminished by absence of resistance to Old World diseases). The most straightforward explanation of the reversal of fortune for territories, then, would be that the connecting of “old” (Eurasia plus Africa) with “new” (Americas, Oceania, and other islands) worlds that began in the fifteenth century led to population transfers in which (inter alia) the technological and social advantages of peoples from the most advanced civilizations sank new roots in previously backward lands.

Critical Comments

1. This is an extremely convincing piece. AJR’s “reversal” evidence was always pretty thin. While CCP are basically able to replicate the reversal, AJR’s results are sensitive to mild tweaks. Adjusting all the results for ancestry, in contrast, dramatically changes the picture.

2. Suppose you knew none of AJR or CCP’s results. You have five measures of early development: urbanization in 1500, population density in 1500, millennia of agriculture, state history, and technology in 1500. A priori, which measures most credibly capture “initial success” that might or might not be reversed? To my mind, technology in 1500 comes in first, followed by a two-way tie between urbanization and population density. State and agricultural history seem least relevant. If a society was barbarous in antiquity but visibly successful in 1500, poverty in 2000 shows reversal, not persistence.

3. If you buy my ranking, CCP’s results are somewhat puzzling. Persistence works well for the best measure (technology), but only slightly for the two runner-ups – urbanization and density. For the least plausible measures, it works best. While it’s tempting to paint whatever measures predict most strongly as the “truest” measures of ancestral development, that’s not good science.

4. While we’re on the subject, none of the papers we’ve examined try to measure early per-capita GDP or use it to predict modern economic performance. They have a standard theoretical excuse: Early economies were Malthusian, stuck at subsistence, so we shouldn’t expect early per-capita GDP to predict current per-capita GDP.

I’ve long been suspicious of this whole story. First, while no pre-modern societies were rich by our standards, their living standards certainly varied. Second, the very existence of slavery shows human beings earned more than their subsistence since antiquity. There’s little point owning a person who eats as much value as he makes. Third, if early per-capita GDP did predict current per-capita GDP, economists would clearly treat this fact as relevant – as they should. By basic Bayesian logic, the alleged failure of early per-capita GDP to predict current per-capita GDP should tip our mental scales in the opposite direction.

Coming up: A general assessment of the ancestry and long-run growth literature, especially as it relates to the case for immigration and open borders, followed by an Ask Me Anything.

READER COMMENTS

E. Harding

Feb 16 2016 at 11:06pm

“They have a standard theoretical excuse: Early economies were Malthusian, stuck at subsistence, so we shouldn’t expect early per-capita GDP to predict current per-capita GDP.”

-Not uniformly true, but it’s probably impossible to measure pre-modern per capita GDP, or do good comparisons between societies. The market was much less developed in earlier times.

“Second, the very existence of slavery shows human beings earned more than their subsistence since antiquity.”

-Good point.

Carl Shulman

Feb 17 2016 at 1:48am

“Second, the very existence of slavery shows human beings earned more than their subsistence since antiquity. There’s little point owning a person who eats as much value as he makes”

The Malthusian wage lets people pay not only for their own support, but that of enough children to replace them (or, alternatively, their training costs). So the ‘subsistence wage’ is really ‘subsistence+child-rearing.’

A slave captured in war or sentenced for crime could thus provide profit to an owner by raising fewer offspring. And indeed slave populations tended to dwindle throughout history for this reason. Slave populations massively growing through natural increase, as in the United States, is a recent phenomenon and occurred under non-Malthusian conditions (with massive population growth across the board in the early U.S. and high wages).

Jim

Feb 17 2016 at 10:35am

The AJR paper hilariously speaks of less developed “civilizations” in Australia and New Zealand in 1500! Of course it is completely obvious why the US, Canada, Australia and New Zealand are much more advanced today than they were in 1500. White people.

Areendam Chanda

Feb 18 2016 at 5:18pm

Bryan

Thanks for choosing to discuss our paper and for your positive reaction.

A few observations.

a) In your view technology is the most preferable variable followed by population density and urbanization, with agricultural history and state antiquity coming last. Further, you observe that technology does “well” in capturing persistence, while your least preferable variables do the best, with density and urbanization doing worst.

The fact that urbanization and density may not do as well is, because we believe that they are poorly measured. Furthermore, for urbanization the small sample size makes matters worse.

Moving on to the other three variables, you prefer technology the most but note that your least preferred variables do better. Having re-examined our results, my own reading is that technology performs at least as well as, if not better, than state antiquity and millennia since agriculture. Note that the simple correlations in our paper indicate that technology, state history and agriculture are very strongly correlated (compared to their correlations with urbanization and population density).

I should also clarify that state history is a “stock” variable that aggregates a measure of the existence of the state over 50 year periods from 1CE to 1500CE. We apply a 5% decay for past values. In other words, it is a stronger indicator of the presence of a state in the centuries closer to 1500, than a 1000 years earlier.

b) You doubt the Malthusian theory of limited GDP per capita differences and suggest that slavery is an indication that living standards are likely to have been above subsistence. Slavery was not uncommon in pre-industrial times though it did vary by country or empire. It would be hard to say how much it would be reflected in GDP per capita differences. If most of the population was still engaged in livelihoods that only provided a subsistence income, this may not have mattered so much. In any case, at least indirectly, variations in the existence of slavery should reflect differences in the power and organization of the state, or the technology that helped capture and retain slaves. In that sense, I think variables such as technology and state history are useful measures when GDP per capita is not available.

Having said, that I now shameless plug my earlier research with Louis that was published in the Scandinavian Journal of Economics in 2007. In that paper, we extrapolated GDP per capita in 1500 based on population density and urbanization. Needless to mention, it is certainly worth exploring further by adding state history and the measure of technology.

Thanks again for choosing to cover the series of papers on ancestry and long run development.

Comments are closed.