This will be a highly speculative post, which is aimed at getting you thinking “outside the box”, not answering any questions. Scott Alexander has a very nice post pointing out that surveys indicate no increase in Chinese happiness since 1999, or perhaps even 1990, despite rapid growth in real per capita income. Then he points to some interesting implications:

Or let me ask a more specific question. Suppose that some free trade pact will increase US unemployment by 1%, but also accelerate the development of some undeveloped foreign country like India into hyper-speed. In twenty years, India’s GDP per capita will go from $1,500/year to $10,000/year. The only cost will be a million or so extra unemployed Americans, plus all that coal that the newly vibrant India is burning probably won’t be very good for the fight against global warming.

Part of me wants to argue that obviously we should sign the trade pact; as utilitarians we should agree with Sumner that lifting 1.4 billion Chinese out of poverty was “the best thing that ever happened” and so lifting 1.2 billion Indians out of poverty would be the second-best thing that ever happened, far more important than any possible risks. But if Easterlin is right, those Indians won’t be any happier, the utility gain will be nil, and all we will have done is worsened global warming and kicked a million Americans out of work for no reason (and they will definitely be unhappy).

I’m going to argue in favor of the Indian trade pact, even if it does cost jobs in America (I don’t think it would), and even if it does not boost reported happiness in India, and even if those surveys are accurate, and even though I am a utilitarian. That’s a lot of hurdles to overcome, but my basic strategy will be to show that the implications of the China result are far weirder than they seem.

Those who have not visited China might wonder if this is somehow due to one of the popular downsides of growth, such as higher pollution levels. I very much doubt it. China’s overcome far more serious problems than pollution. Life expectancy is rising rapidly. A more likely explanation is the sort of “arms race” that has young Koreans studying ridiculously long hours, to private benefit but no social benefit.

Here’s one puzzle in the happiness surveys. Back in the 1970s, China was so poor that people often suffered severe pain due to poverty. (Poorer than India was in the 1970s.) Hunger was probably the biggest problem, but untreated medical conditions were also a big problem. So why hasn’t the virtual elimination of poverty itself caused the Chinese to become happier? Surely at least those who are no longer in pain are happier. If the survey results are to be believed, then any gains in happiness to some Chinese were offset by losses for other Chinese.

But if trade is your agenda, then this is a theory that proves too much. If nothing really matters in China, if even overcoming horrible problems doesn’t make the Chinese better off, then what’s the use of favoring or opposing any public policy? After all, America also shows no rise in average happiness since the 1950s, despite:

1. A big rise in real wages.

2. Environmental clean-up (including lead–does Flint matter?)

3. Civil rights for African Americans

4. Feminism, gay rights.

5. Dentists now use Novocain (My childhood cavities were filled without it)

6. 1000 channels in glorious widescreen HDTV

7. Blogs

I could go on and on. And yet, if the surveys are to be believed, we are no happier than before. And I think it’s very possible that we are in fact no happier than before, that there’s a sort of law of the conservation of happiness. As I walk down the street, grown-ups don’t seem any happier than the grown-ups I recall as a kid. Does that mean that all of those wonderful societal achievements since 1950 were absolutely worthless?

But there are exceptions. I recall reading that surveys showed a rise in European happiness in the decades after WWII, and Scott reports that happiness is currently very low in Iraq and Syria. So that suggests that current conditions do matter.

The following hypothesis will sound really ad hoc, but matches the way a lot of people I know talk about their lives. Suppose people’s happiness is normally calibrated around the sort of lifestyle that they view as “normal.” As America got richer after 1950, it all seemed very normal, so people didn’t report more happiness. Ditto for China during the boom years. Everyone around you was also doing better, so you started thinking about how you were doing relative to your neighbors. But Germans walking through the rubble of Berlin in 1948, or Syrians doing so today in Aleppo, do see their plight as abnormal. They remember a time before the war. So they report less happiness than during normal times.

I seem to recall that there is also some evidence that different cultures have different attitudes toward proclaiming one’s happiness. I read that in Japan it’s not considered polite to go around talking about how happy you are. (Can anyone confirm that?) At the same time, I also think it’s quite possible that Latin Americans really are happier than Eastern Europeans, or Asians.

Now let’s return to the trade issue. Suppose nothing seems to affect the happiness of the Chinese, even eliminating mass hunger. That suggests that for every Chinese person who gained (if only from less pain), someone else lost. But if that’s right then there would be no reason to worry about Indian exports causing a million Americans to lose there jobs. Nothing will affect average happiness in America. Those million workers may be less happy, but someone else will be happier.

At this point people on the left will bring up the equality issue. It’s not about boosting GDP, it’s about boosting equality, because people compare themselves to their neighbors. I think there’s a bit of truth to that, but the happiness surveys don’t support that claim either. The US scores higher than Europe, even though Europe is more equal. Latin America scores higher than East Asia, even though Latin America is far less equal than places like South Korea and Japan.

If happiness surveys are correct, and basically nothing matters short of horrific war, then its bad news for all ideologues. For leftists claiming equality will make us happier. For right-wingers talking about economic growth.

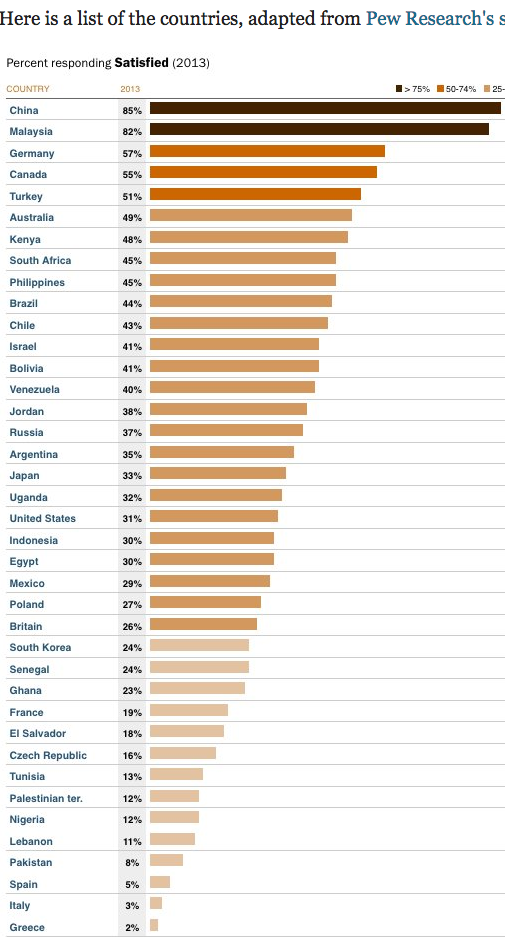

In the end, I think we need to be very careful here. Surveys show that the Chinese people feel very strongly that China as a whole is much better off than in 1980. They are very proud of the fact that gleaming skyscrapers are transforming their dirty grey rundown cities. Crappy trains are replaced with high-speed rail. They are happy to be able to leave rural squalor and move to the cities. They can eat meat. They are happy to see their children much better off than they were. Here’s an example from Pew Research, which asked how satisfied people were with their country’s direction:

Suppose we were going to base our trade policy on happiness surveys. We might conclude it doesn’t matter for either the US or India, because nothing matters. We might also conclude that civil rights, gay rights and HDTV do not matter. (But don’t you dare take away my Novocain!)

Or we might conclude that “utility” is not identical to self-reported happiness, and that utility also includes the sorts of considerations that make the Chinese extremely pleased about the economic progress their country has made.

In my view, the safer course is to admit our uncertainty. If I’m wrong, and the happiness surveys are telling us all that we need to know about maximizing utility, then perhaps nothing really matters. On the other hand, if Blaise Pascal were alive today he might recommend that we’d be better off basing our public policy decisions on a theoretical framework that assumes policy decisions do matter, and implement the policies that work best if they do in fact matter.

READER COMMENTS

Thomas

Mar 24 2016 at 4:54pm

I doubt the validity of cross-temporal happiness surveys. But even if they show something about “average” happiness, so what? You have to be a deeply committed utilitarian to believe in something called aggregate happiness or utility, and to believe that it’s the thing to be maximized. That kind of utilitiarianism strikes me as an intellectual pose, on a par with collegiate Marxism. A strong utilitarian must be (actually) willing to sacrifice a large chunk of his own happiness for the greater good of humankind.

If it’s true that Americans aren’t any happier on average than they were in the 1950s, perhaps it has something to do with some of the items on your list, and a whole bunch of negative things that you haven’t listed: e.g., breakdown of traditional family structures, a less religious and more permissive culture, and the conversion of many once-quiet, small cities to crowded, congested urban complexes. And that’s just for starters.

dlr

Mar 24 2016 at 5:25pm

Thomas, the phenomena Scott is referencing goes way beyond intertemporal surveys or differences between conditions that might seem ambiguously conducive to welfare in the first place. The famous Brickman study compared the happiness of recent lottery winners to recently paralyzed paraplegics and quadraplegics and showed enormous set point tendencies. Scott is right that if we want to construct economic policy to optimize “happiness” as opposed to revealed preference it is a slippery slope. Pretty much the only thing we would know for sure to do is spend every available resource to make sure people don’t regularly sit in traffic.

Daniel Klein

Mar 24 2016 at 5:47pm

If you went back in time and asked Adam Smith whether he was short or tall, he would say he is average. But if he came to life today we would call him short.

BTW, here are some quotes on happiness:

Georg Simmel:

“Happiness is the condition in which the higher psychic energies are not disturbed by the lower—comfort is the condition in which the lower are not disturbed by the higher.”

Adam Smith:

“But in every permanent situation, where there is no expectation of change, the mind of every man, in a longer or shorter time, returns to its natural and usual state of tranquillity.”

And La Rouchfoucauld:

“It is a form of happiness to realize how unhappy we are fated to be.”

Sieben

Mar 24 2016 at 5:52pm

What about the counterfactual? That Chinese would be really, really unhappy if their nation had stagnated while the rest of the world continued to grow.

Phil

Mar 24 2016 at 6:01pm

Happiness is an emotional response, typically fleeting, to some stimulus. A smile, an invitation to lunch, a baby’s laugh, a $20 bill found in a coat pocket — these things make one happy. I don’t understand why anyone would want to correlate economic policies with such a thing. Economic policies should create wealth and value or utility, but wealth and value do not necessarily correlate with happiness. Nor does utility. I could negotiate a great bargain on a root canal, but I ain’t happy about it. I may be better off, but not happy.

No, economics should look at non-emotional and objective indicators of policy success: welfare measures such as access to food, healthcare, jobs, and housing. By those measures, the average person in China has made great gains.

Handle

Mar 24 2016 at 6:22pm

It’s certainly strange to say that, on the one hand, we really don’t have a good understanding at all of the neurobiology and psychology of human happiness, but also say, on the other hand, we have this philosophical ideology which can help us make pragmatic decisions about policies based on estimates of what would maximize that mysterious thing, even putting aside objections such as those relating to non-commensurability.

And after all, no one is happier than a junkie getting his fix, so why not just wire up every brain to electrodes set to induce constant pleasure? Or better yet, turn the whole world into computers to emulate the brains of humans experiencing that moment of total bliss over and over quadrillions of times a second. That’s obviously a fantastically higher utility state than we have now, but almost no one accepts this implication. Some people bite that bullet, but most don’t.

All of this is to say that these kinds of results should be taken as an opportunity to reflect and question one’s dedication to any artificially concocted teleology centered around some metaphysical constructs.

A lot of people are utilitarians simply because they don’t want to be meta-ethical moral nihilists (a very socially abhorred, unnatural and effectively unsustainable perspective for the vast majority of humans, which is understandable given what we know about the evolutionary origins of the psychology of our moral intuitions). So, faute de mieux, they latch upon the most scentistic-seeming, pseudo-objective alternative at hand. But that doesn’t mean it’s not, at root, a mirage.

Matt Moore

Mar 24 2016 at 7:33pm

I don’t trust happiness surveys.

People in poor countries observe happiness from 0 to 75 and force that into a 10 point scale.

People in touch countries observe happiness from 10 – 90 and force their position in that distribution into the same 10 point scale.

On a completely separate note, I used to analyse consumer satisfaction data. There were large and persistent differences in responses between nations, for a wide array of identical products. Some is language, some is culture

Don Geddis

Mar 24 2016 at 7:34pm

Perhaps relevant quote from Abd ar-Rahman III of Spain, 960 AD:

john hare

Mar 24 2016 at 8:33pm

Many people are hardwired to look at the downside. So what else is new?

AbsoluteZero

Mar 24 2016 at 8:58pm

As others have mentioned, so-called happiness surveys are highly problematic. There are issues with set points, return to mean, expectations, and so on. I don’t think they’re completely useless, but they’re misleading. They do tell us at least one thing, how people respond to happiness surveys. I think they also tell us two things, both indirectly. One is a reflection of a person’s life experiences. The other is differences between cultures (including language).

“I read that in Japan it’s not considered polite to go around talking about how happy you are. (Can anyone confirm that?)”

Yes and no. It’s not so much that it’s considered not polite to do so, and that’s the reason, although many no doubt do consider it also impolite. To put it simply, it’s that it’s weird. It’s hard to explain, but it’s a bit like how many East Asians (not just Japanese) find really big smiles that many Americans have to be weird, and, at least in some cases, in some sense, somewhat impolite.

Scott Sumner

Mar 24 2016 at 9:43pm

Everyone, Lots of good comments, and yes measuring happiness raises all sorts of issues. The measurements are probably correlated with positive brain states at the individual level, and perhaps at the country level, but with lots of caveats. If the great writers and philosophers don’t have this concept figured out, I certainly cannot do so.

Daniel, Thanks, those are nice quotations.

Sieben, Yes, that’s very possible.

Handle, The main reason why I am a utilitarian is that I don’t find anti-utilitarian arguments to be persuasive.

If there’s a happiness machine that I can hook up to my brain, I’ll buy it!! The main reason I don’t become a junkie is that they don’t seem very happy, nor do their friends and family.

Don, Great quote. I’ve also had about 14 happy days–give or take 1000. People sometimes think this is weird, but I have no idea whether I am happy or not. Some days I think I’m happy most of the time, and other days I think I’m unhappy most of the time. How do I know which view is correct?

AbsoluteZero, Thanks for the info. I recall reading that Japanese ladies should cover their mouth with their hand, when giggling. But I don’t know if that’s an old fashioned cultural trait, which doesn’t persist today. (I’ve never visited Japan, outside an airport.)

I will say that Thai people looked happier than Chinese people, when I visited each country. But I have no idea whether they actually were happier.

AbsoluteZero

Mar 24 2016 at 10:04pm

Scott,

“I recall reading that Japanese ladies should cover their mouth with their hand, when giggling. But I don’t know if that’s an old fashioned cultural trait, which doesn’t persist today.”

Most of them do, but again it’s not really covering. A lot of times she’ll just raise her hand, perhaps balled up loosely into a semi-fist, and keep it there for a second. It’s often subtle, but yes, most of them do this.

“I’ve never visisted Japan”

You should, seriously. I think a lot of us would like to know what you think.

TravisV

Mar 24 2016 at 10:23pm

Prof. Sumner,

A few years ago, you wrote an excellent post on this topic. Below is an excerpt:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=8311

“I claim that Mexico is a country with very low utility, full of very happy people. Think of ‘happiness’ as “personality,” and think of ‘utility’ as “living conditions.””

Daniel Kahn

Mar 24 2016 at 11:37pm

This is reminiscent of a post you wrote a while ago. Something to the effect of acknowledging that Mexico may very well be the happiest country in the world and happier than the U.S., but that the U.S. had greater utility and that these were different things. I think in this framing utility can be seen as akin to self-actualization or the potential for such.

Lorenzo from Oz

Mar 25 2016 at 2:24am

People experiencing the same level of average happiness while living longer lives is an increase in happiness, just not average happiness.

Benjamin Cole

Mar 25 2016 at 7:33am

Happy? Theologians and central bankers say you are not supposed to be happy. Quit your sniveling.

And in China they paid a huge price, in terms of inflation, for their 30-year-long development boom. No wonder they are not singing.

D. F. Linton

Mar 25 2016 at 7:44am

Surprising that an economist would blog about survey-based happiness measures without looking for revealed-preference proxies. For example, Chinese suicide rates have been falling with increased global trade and today are quite low in international rankings.

Despite they future directions speculation in the article below the graph it includes is quite clear.

http://qz.com/227136/chinas-suicide-rate-has-plummeted-because-of-urbanization-but-it-may-be-climbing-again/

B. Reynolds

Mar 25 2016 at 10:17am

I wonder what response you’d get if you asked Chinese people if they’d be more or less happy for economic conditions to return to 1980 levels.

Noah

Mar 25 2016 at 10:37am

Different words are used for “happy” in different languages, and cover different scopes of meaning. Check your English thesaurus for “happy”, and think about the extent of differences between the different words, and consider that cultural differences are not even relevant yet.

One might report “happiness” in consideration of the neighbours. But there can be little doubt that advancing from rice and tofu to meat and vegetables, tin huts to modern constructed apartments, barefoot farm labour to diverse opportunities in the market, or from virtually zero IT to nearly uniquitous mobile phones. The proof is in the pudding: Nearly any person on the planet will choose the one rather than the other. Maybe it doesn’t cause them to report a higher number when asked “rate how happy you are on a scale”, but there can be little doubt that the improvements in material living standards have had a huge positive impact on how much the can, say, enjoy their day or access a greater variety of meaingful ecxperiences and opportunities. Sure, you can get satiated and accustomed to a new norm, but I have a hard time imagining getting equal enjoyment out of a bowl of plain white rice with unsanitary water and a meal with a diversity of meat and vegetables shared with friends.

However, there is way more pressure on Chinese people than during the poor times, especially at a younger age. Keeping up with the Jones’ is hard work, and when there’s only one child, pressures to succeed (the retirement plan) are huge.

Scott Sumner

Mar 25 2016 at 10:57am

Absolutezero, I hope to do so in 2018. Right now Japan is probably my favorite country, just based on its film, graphic arts and literature.

Travis and Daniel, Thanks, but that just reminds me of how my blogging has deteriorated. I like that much better.

Lorenzo, Yes, I was going to mention that and completely forget—good point.

DF, You said:

“Surprising that an economist would blog about survey-based happiness measures without looking for revealed-preference proxies.”

I’ve done that in other posts. For instance, I pointed out that surveys show very high happiness in Central America and Mexico, and yet its citizens struggle through horrible hardships to reach the US, in order to pick vegetables in the hot sun for low wages, always being afraid of the cops picking them up as an illegal.

B. Reynolds, No need to wonder, I can just ask my wife!

Meets

Mar 25 2016 at 3:47pm

Happiness, to a certain extent, is biologically fixed.

And it doesn’t much sense to conduct policy on that basis.

I can be just as “happy” eating a mediocre dinner or movie over great ones. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a difference.

Dustin

Mar 26 2016 at 9:31am

Happiness, whether accurately measured or not, probably isn’t the correct benchmark. It’s like asking if increased wages have caused more people to fall in love. The concepts aren’t deeply related.

Happiness is much more about the value of one’s relationships, social interactions, perceived success against expectations, feeling of accomplishment, etc. Beyond a quite low threshold, I suppose that GDP doesn’t have any effect on what causes happiness.

I’ll take an easier, less stressful, entertainment-filled, anesthetized, long-lived life every time, even if I’m not consciously happier because of it.

Michael S. Gross

Mar 26 2016 at 1:12pm

I am a few years older than Prof. Sumner but I do remember that Novocain was available when I was a child. But like Prof. Sumner, I had my teeth drilled without it. When the dentist offered Novocain, I had to refuse, because there was an extra charge for it. I did not want to anger my father, who did not like paying extra for anything.

Sean

Mar 26 2016 at 5:39pm

If a GDP rise doesn’t affect instantaneous happiness but it increases life expectancy then it’s still good for total happiness, isn’t it?

ChrisA

Mar 27 2016 at 8:18am

Happiness always seemed a strange thing to try to optimise, why not try to reduce pain or misery? I would rather have a thousand people slightly glum if it meant one person wasn’t being tortured.

Mark

Mar 27 2016 at 8:19pm

[Comment removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Swami

Mar 28 2016 at 10:34am

To be brief:

Beware using a population measure which is “attracted” toward the median.

Longer version:

Happiness is intrinsically pulled away from the extremes and toward mid rankings because it is greatly a measure of relative not absolute satisfaction. See Rayo and Becker.

http://www.econ.nyu.edu/user/debraj/Courses/NewRes08/Papers/rayo_becker_07.pdf

Relative to what?

1). To our peers. This creates problems because on a broad scale it is zero sum. If one does better relatively, the others are doing relatively worse. On an individual basis, this also presents the problem of changing peers. As we do better, we change our references, until we hit a Peter principle of averageness. Peer based relative measures are attracted in multiple ways toward average rankings.

2). To our expectations. In Christmas Vacation, Griswald had a breakdown after receiving a gift or bonus of a jelly of the month subscription. Why did this cause a breakdown? He expected a better cash bonus to buy a pool. Absolutely the jellies were a gain, but relative to his expectation they were the the final straw. The trouble again is that as our situation improves so to do our expectations, thus neutralizing happiness improvement. This is true in many fields, not just economics — love, proficiency at sports, so on.

3). To our past. This one will go slightly higher if we are on net experiencing steady cumulative gains, but even here, it won’t keep going up and up and is easily countered by relative losses on the prior two dimensions. It also presents the problem of goal switching (something Griswald also does as he reverts to realization that it was really only family that matters, not pools). People often switch from one goal to another after extensive journeying.

4). Finally, there is the issue of survivors bias, again pulling populations toward average happiness. Those suffering from disease and starvation tended to drop out of the population. Same thing with people who are fired from a company.

I know this attraction toward the middle rankings is tough for people to grasp. And I agree that it doesn’t completely explain away happiness trends. But once you see the attractor, it makes one less likely to assume there will be strong correlations between absolute improvement and happiness.

Comments are closed.