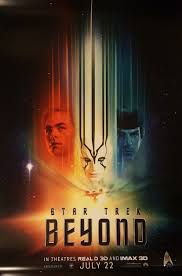

I recently watched “Star Trek Beyond” and liked it a lot. Visually, I think it’s one of the most astonishing science fiction movies ever. The USS Enterprise “parking” inside a space station is perhaps the single most impressive scene I’ve ever seen.

Of course, “Star Trek” is renowned for being more than a mere “space opera.” It was a product of Cold War anxiety and the enduring memory of World War II. Its creator, Gene Roddenberry, imagined a spaceship in which an American captain could trust a Russian navigator, a black woman was the indispensable communication officer, and a bizarre Vulcan a much respected and authoritative aide to the ship’s captain. “Star Trek” is a plea to understanding and brotherhood among different peoples, seeking peace all together after much strife. Alas, not unlike many others, Roddenberry apparently saw economic life as a main driver of tension and conflict. Therefore, in the pacified Federation of Planets he imagined there is no use of money – and exchanges and transactions happen somehow like magic, clearly helped by bountiful technology.

“The Economist” has run a piece on “Star Trek Beyond,” arguing that

“Star Trek”‘s producers now take their task of stripping politics out of their movie universe. The television series and some of the films studiously explored the big moral questions facing a bloc as diverse as the Federation, from the limits on cultural integration right through to how a peace-loving organisation should tackle imperial forces. The three most recent “Star Trek” films strip out these moral and global questions, and instead focus on how to stop bad guys who want to kill a lot of people.

“The film,” the Economist argues, “misses an opportunity to probe interesting questions and test the idea of liberalism. The film misses an opportunity to do what “Star Trek” does best.” Wow.

The new “Star Trek” is certainly more action movie than philosophical science fiction. But this very latest endeavour tries to revive/stress the message of fraternity of the original series. I don’t want this post to be too much of a spoiler, but the bad guy considers the Federation basically decadent and rotten precisely because of its ambition to eradicate violence and conflict. He considers preposterous the idea that people can be peaceful “explorers” in the galaxy, as he believes that only conflict and struggle improve intelligence and alertness (we might say: the race). This is a lesson he wants to teach so desperately, that he commits incredible evil for its sake and doesn’t hesitate to destroy his own community.

Quite frankly, I sense the movie is, this time, certainly “political”: as much as a contemporary action movie can be, which is certainly different from an experimental (and unsuccessful) 1960s TV series. I sense the problem is not with the story lacking a political morality: the problem is that the political morality is very naive, a sort of a trivialisation of the much common denunciation of “social darwinism.”

In these days of sadness, fear, and division, it’s good to say to people that we should stick together and benefit from each other’s differences and talents: but it’d be better to explain to them how this could be done. And this could be done, I’m afraid, precisely thanks to decentralised coordination mechanisms like the market, instead of trusting a vertical organization such as Starfleet.

Having said this, I shall add two other comments. First, if “Star Trek” is indeed about a future in which Starfleet is all powerful and, apparently, wise, all its heroes basically go the other way and disobey orders. James T. Kirk is in many ways the quintessential individualist, who has little patience with prescriptions sent from a distant and bureaucratic High Command and does what he feels right. It’s a kind of highly discretionary leadership style, and I won’t recommend it for a country: but it’s always great fun to see Kirk revolting against what he considers ill-informed and ill-considered orders from above (this doesn’t happen in Star Trek Beyond, though).

Second, the message, this time, is indeed that cooperation (“society”) is fruitful because of individual differences. The good crew of the USS Enterprise doesn’t win just because they are “united,” but because they are different; each of them has different talents, Scottie is not so brave as Kirk, Uhura is keen on language and is also rather perceptive, even Bones and Spock are a great team precisely because they are different. Though all of this doesn’t find, so to say, the proper institutional setting (and should it? Come on, it’s a movie!), the message is indeed refreshing, particularly in these days.

READER COMMENTS

TMC

Jul 28 2016 at 11:35am

Pretty good analysis. Star Trek has alway been a weird mix of socialist idealism and libertarianism. I guess the socialistic part is OK is a post scarcity world.

Harold Cockerill

Jul 28 2016 at 4:03pm

TMC – post scarcity and science fiction are made for each other. In this respect Heinlein is more down to earth.

Comments are closed.