Back in the 1980s and 1990s, I did some research with Steve Silver on sticky wages and the business cycle. Using postwar data, it’s very difficult to draw any conclusion, as the economy was hit by both supply and demand shocks, which have very different impacts on real wages.

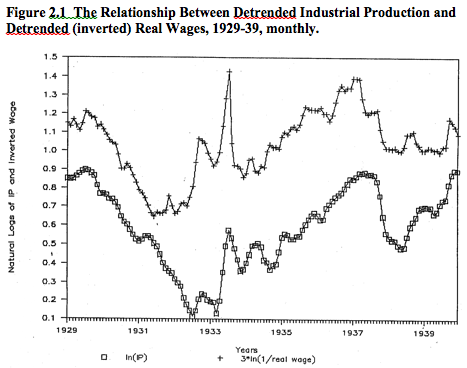

During the interwar period, however, demand shocks are much easier to identify and the role of wages really stands out. In the following graph we inverted the real wage series (top line), and compared it to industrial production (bottom line), to make it easier to see the strong countercyclicality of real wages:

We found that there were two factors that reduced output during the interwar years. First, falling prices in the face of sticky wages—which occurred on and off throughout the entire interwar period. Second, an autonomous rise in nominal wages (caused by government labor market policies)—which mostly occurred during the period after 1933.

While cleaning out my office I came across a 1996 QJE paper by Ben Bernanke and Kevin Carey. Here’s a portion of their conclusion:

First, like Eichengreen and Sachs [1985], we verified that during much of this period there existed a strong inverse relationship (across countries as well as over time) between output and real wages, and also that countries which adhered to the gold standard typically had low output and high real wages, while countries that left gold early experienced high output and low real wages. It does not appear that any purely real theory can give a plausible explanation of this relationship. Among theories emphasizing some type of monetary non-neutrality (i.e., a non-vertical aggregate supply curve), there are basically only two types: theories in which the price level affects output supply because of nominal-wage stickiness, and theories in which the price level affects output supply for some other reason. We find that, once we have controlled for lagged output and banking panics, the effects on output of shocks to nominal wages and shocks to prices are roughly equal and opposite. If price effects operating through nonwage channels were important, we would expect to find the effect on output of a change in prices (given wages) to be greater than the effect of a change in nominal wages (given prices). As we find roughly equal effects, our evidence favors the view that sticky wages were the dominant source of non-neutrality.

That’s why Bernanke was my first choice for Fed chair back in 2006.

PS. Is the 1985 paper that Bernanke and Carey cite co-authored by the Jeffrey Sachs who defended Bernie Sanders and a higher minimum wage? I believe it is. I think it’s fair to say that the policy views of economists are not based on the outcome of their empirical research.

PPS. Steve Silver and I had a paper on real wage cyclicality published in the 1989 JPE. We did a follow-up paper focusing on wages and prices during the interwar years, which was published in 1995 in the Southern Economic Journal.

READER COMMENTS

James

May 21 2017 at 4:42pm

Why does the condition occur over and over (not just during the interwar period) that wages exceed workers’ marginal revenue products, leading to either layoffs or business failures?

This is not just an academic question. Without knowing the ultimate cause of the problem, it is impossible to know if any policy response will alleviate or exacerbate the problem.

Andrew_FL

May 21 2017 at 5:50pm

This was actually something like the pre-Keynes consensus view of unemployment.

You can broadly explain much of the cyclical variation in total employment/unemployment with W/PI (roughly equivalent to W/NGDP except PI is available monthly back through to the late 20s). I think it’s overstating it to call this a theory of the business cycle, however.

Rajat

May 22 2017 at 1:24am

Apparently, these days, simply being able to develop a model in which labour markets are not perfectly competitive is enough to justify higher minimum wages:

IGYT

May 22 2017 at 7:42am

And can we add, “nor vice verse” just as safely?

Scott Sumner

May 22 2017 at 8:48am

James, The rising real wages were caused by either falling prices or government labor market policies such as the minimum wage.

Andrew, Yes, it is the pre-Keynesian view. And thanks for the tip on personal income.

Rajat, Even worse, those monopsony models where minimum wages don’t cause unemployment are also models where higher minimum wages don’t cause higher output prices. But the empirical evidence suggests they do, so the monopsony model doesn’t explain minimum wages.

IGYT, Good question.

IGYT

May 22 2017 at 4:49pm

And can we add, “nor vice verse” just as safely?

Federico

May 26 2017 at 8:30am

Scott, re the comment about the post way period — can you identify shocks to supply vs shocks to demand? Perhaps looking at how breakeven inflation (or just nominal rates) react relative to stocks?

Comments are closed.