Arnold Kling recently posted on the implications of the Modigliani-Miller (M-M) theory of corporate finance for monetary economics. He seems to suggest that open market operations will not significantly affect the price level, even when interest rates are positive. (Although it’s possible I’ve misread his post):

The metaphor that I would propose is that a single firm’s changes to its financial structure is like me sticking my hand in the ocean, scooping up water, and throwing it in the air: I don’t make a hole in the ocean.

Modigliani-Miller is not strictly true. But it is the best first approximation to use in looking at financial markets. That is, you should start with Modigliani-Miller and think carefully about what might cause deviations from it, rather than casually theorize under the implicit assumption that it has no validity whatsoever.

Taking this approach, I view the Fed as just another bank. Its portfolio decisions do not make a hole in the ocean. That heretical view is the basis for the analysis of inflation in my book Specialization and Trade.

*Sumner’s response is actually beside the point, in my view. The Modigliani-Miller theorem does not in any way rely on different asset classes being close substitutes. It relies on financial markets offering opportunities for people to align their portfolios to meet their needs in response to a corporate restructuring.

I have the opposite view. I believe that money is neutral in the long run and that if you permanently and exogenously double the monetary base through open market operations, this action will double the price level.

Consider the following example. Apple decides to exchange tens of billions of dollars of T-bills for another asset, say palladium. Let’s say Apple suddenly buys up 30% of the world’s stock of palladium. As a first approximation, the value of Apple has not changed–they simply exchanged one asset for another at current market prices.

But the market value of palladium has likely increased sharply! If palladium were the medium of account when this occurred, then Apple’s portfolio readjustment would be highly deflationary. Indeed something quite like this caused the Great Depression.

You might argue that palladium has nothing to do with M-M, and I’d agree. But my claim is that cash is much more like palladium than it is like stocks or bonds, which are the sorts of assets envisioned when people discuss M-M. In 1981, $100 bills yielded 0% while one-month T-bills yielded nearly 15%. These assets are clearly not close substitutes. When the government exchanges T-bills for T-Notes, the financial markets yawn. When the Fed (implicitly) announces a plan to exchange T-bills for cash, the global market value of all stocks can decline by trillions of dollars in seconds. There’s a good reason why stock investors believe I’m right and Kling is wrong; cash and T-bills are not close substitutes.

I’ve spent my whole life looking at the impact of open market operations (OMOs) on macro variables, as have much smarter people like Milton Friedman. There’s no doubt in my mind that exogenous and permanent OMOs have a huge impact on the economy, at least at positive interest rates and very likely at zero interest rates as well. That’s not in doubt. The question we need to examine is not, “Does M-M help us to understand monetary policy?” Rather the interesting question is, “Why doesn’t M-M help us to understand monetary policy?”

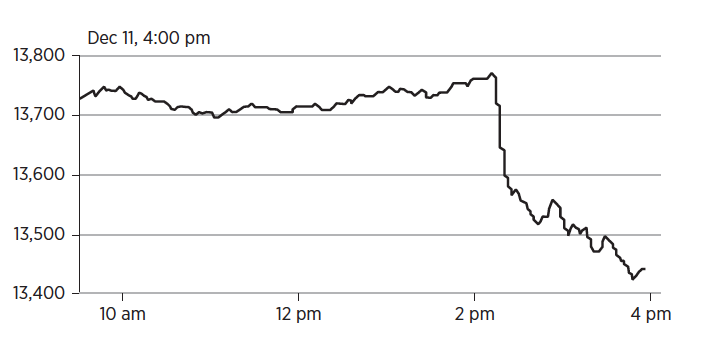

PS. At 2:15 on December 11, 2007, the Fed made an announcement. The didn’t even mention “cash”, but the only way to implement their announced policy was to reduce the growth rate of cash to a level below what the market had expected 5 minutes earlier. This is how the stock market (DJIA) responded:

Stock investors don’t seem to believe that M-M applies to OMOs.

READER COMMENTS

Market Fiscalist

Oct 28 2020 at 9:48pm

If I remember my Nick Rowe correctly then Kling is neglecting money’s role as the the unit of account.

Scott Sumner

Oct 28 2020 at 10:56pm

It’s an interesting question as to why M-M doesn’t apply. It may be the medium of account function of cash, or perhaps M-M is a micro perspective, which takes the value of money as a given, whereas OMOs have important macro effects on the value of money. M-M does apply for a swap of $50 bills for $100 bills, or T-bills and T-notes.

Market Fiscalist

Oct 29 2020 at 9:31am

I’m totally out of depth here but is this an issue of real v nominal ? As the CB swaps bonds for money its real value (after an adjustment period) stays the same. But the fact that money is the unit of account means that nominal prices (and the nominal value of the CB) increase as a result in the change in the supply of money.

Quite an interesting topic

Market Fiscalist

Oct 29 2020 at 9:42am

In other words in the long run (or in a world of instantly adjusting prices) M-M will mean that CB assets swaps will have no effect on anything except (if one of the assets is money) the price level. But if prices happen to be sticky CB actions may have significant macro-level effects in the short-run.

Scott Sumner

Oct 29 2020 at 12:10pm

I suspect that’s part of the story, but not the entire story.

Market Fiscalist

Oct 29 2020 at 12:52pm

From what Kling has written else where it seems he thinks that swapping bonds for money has no effect on the price level and that inflation is driven by government deficits. This actually seems very close to the MMT view.

Knut P. Heen

Oct 29 2020 at 1:21pm

M&M talk about the right-hand side of the balance sheet, not the left-hand side. Their idea is that two identical corn fields will produce the same amount of corn even if one is equity financed and the other is debt financed. If you replace corn with potato in one field, there is no reason to believe that the fields produce identical incomes or returns.

Brian

Oct 29 2020 at 3:42pm

Notwithstanding the contention with Kling which seems to be about whether a theory is true across all time and supported by examples from 1981 and 2007, I want to ask about current conditions.

What about the effectiveness of open market operations today when the rate paid on excess and required reserves is 10 bp and the 3 month Treasury bill yield is about the same?

Comments are closed.