Two contemporary books of political economy and political philosophy that any student of public affairs must absolutely read are Anthony de Jasay’s The State and James Buchanan’s Why I, Too, Am Not a Conservative. De Jasay defined himself as both an anarchist and a (classical) liberal; I have suggested that “conservative anarchist” might be a better description, but perhaps it should be “conservative-liberal anarchist.” Buchanan, a man of the Enlightenment, was squarely a (classical) liberal, but not an anarchist.

I review Buchanan’s Why I, Too, Am Not a Conservative in the current (Spring 2022) issue of Regulation. I explain:

Buchanan was a radical liberal, but he was not an anarchist. He believed that a limited government and the rule of law are necessary for the maintenance of a free society. The more men are angels (to use Madison’s terms) — that is, the more they follow an ethics of reciprocity — the less government is needed. The less ethical they are, the more they need government (up to the breaking point where the politicization of everything reduces both public and private morality). Private ethics and government controls are thus substitutes. Perhaps libertarians (including the present author) have tended to underestimate the importance of private ethics and to reject notions of fairness too easily.

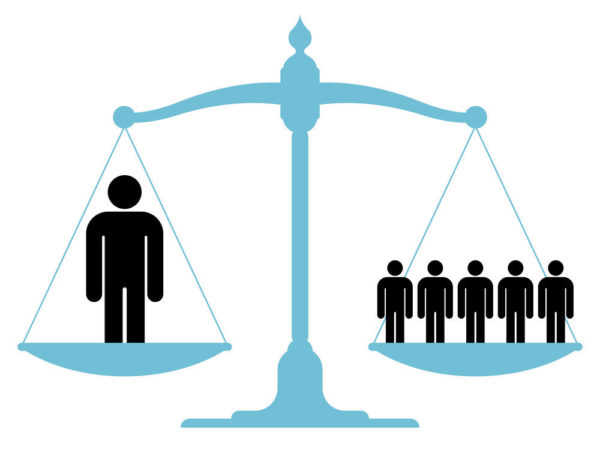

One major point on which Buchanan and de Jasay agreed is that there is no “public interest” defined in a utilitarian way, that is, by comparing and adding utility across individuals as cost-benefit analysis aims to do. In my review, I highlight Buchanan’s point as follows:

The idea of a general interest individually defined illustrates his constant striving to define all values only in terms of individual values, with all individuals being equal. Nobody can define values for others; only the consent of all individuals is acceptable. In this approach, the arbitrary aggregation of individual utility into some concept of social welfare can only produce an arbitrarily defined “public interest.” …

He persuasively argues that only such an integrating normative ideology can win against the soul or “animating principle” of socialism. We must see policy proposals “in the larger context of the constitution of liberty rather than in some pragmatic utilitarian calculus.” We can add that many economists, often brilliant ones, accept simple utilitarianism without reflecting on its philosophical foundations and its implications. They notably ignore that interpersonal utility comparisons — weighing the benefits of some against the costs imposed on others — lack any scientific grounding.

READER COMMENTS

Daniel Kian Mc Kiernan

Mar 25 2022 at 7:58pm

The presumption of interpersonal comparison and aggregation is that meaningful arithmetic may be performed on the respective well-beings of two or more people.

Most economists who attempt to speak or to write about this matter use the words “cardinal” and “ordinal” without careful thought as to what they mean, and when some economists say “cardinal” they make stronger presumptions than do others, while when still other economist say “ordinal”, they assume far less than do many.

The question is of just how much meaningful mathematics can be done. A range of claims (as claims) is possible.

If the well-being of a single person is not complete ordered — if some pair of potential states neither is equally good nor has one outcome better than another — then no quantities can be fitted even as proxies to his or to her well-being, so no arithmetic is possible.

If the well-being of a person is completely ordered, then the ordering can at least be proxied by a quantification, but the quantification may not be meaningful as anything beyond a proxy, and any monotonic transformation of that proxy may be equally suitable as a proxy. Something else — but what? — would have to tell us that a more meaningful quantification existed, and an existence proof wouldn’t necessarily identify which quantification were meaningful.

Expected utility entails a dual quantification, of well-being and of probability. Moreover, if some such quantification fits behavior, then not just any monotonic transformation of the quantification of well-being is equally suitable; only the affine transformations will still work. But uncountably many affine transformations will work. An argument would be needed for a claim that, known to us or not, one of these quantifications is more meaningful than the others, such that arithmetic across persons has meaning. Moreover, if we don’t know which of these infinitely many quantifications is meaningful, then hoping that our mistakes in comparison and in aggregation will “cancel-out” is hoping that infinities will “cancel-out”.

Of course, my own published work has attacked the presumptions that preferences and probability orderings are complete.

Pierre Lemieux

Mar 25 2022 at 10:52pm

Daniel: Thanks for this contribution. I would not claim to be up to your level of mathematical analysis, including your 2012 Journal of Mathematical Economics article. But if I understand well, it reinforces de Jasay’s and Buchanan’s conclusion. As co-blogger David Henderson put it on Econlog in 2015, interpersonal utility comparisons with von Neumann-Morgenstern utility functions are not possible. I understand that you provide a demonstration that this is correct.

Even assuming that preferences and probability orderings are complete, you penultimate paragraph above expresses that conclusion (that interpersonal utility is not comparable) neatly.

Comments are closed.