People often say that central banks cannot magically create jobs when government lockdowns are closing down many industries. That’s correct. But it’s equally true that central banks can make the problem even worse that supply-side factors alone would mandate.

Textbook theory suggests that monetary policy should react to an adverse supply shock by allowing the rate of inflation to increase. This is one case where textbook theory is correct. An increase in inflation would help to reduce the number of debt defaults and also the amount of unemployment.

Recently, I’ve been advocating level targeting of prices, or better yet NGDP. Because NGDP level targeting is not on the table right now, I’ve suggested price level targeting (along a positive 2% trend line) as a bare minimum. I’ve received some criticism from people who point out that inflation should increase above 2% during an adverse supply shock, and that NGDP level targeting would be better.

That’s all true. But my response is that even price level targeting would be far better than the actual policy we are likely to get over the next few years. There are many indications that inflation will stay well below 2% for the foreseeable future. I can’t emphasize enough that this is the wrong policy. While monetary policy cannot magically prevent a fall in RGDP this year, it can “magically” create any inflation rate the Fed desires, even Zimbabwe-style hyperinflation. So is 2% inflation too much to ask for?

Now it’s true that I don’t know for certain that inflation is likely to fall below the 2% target, but that outcome seems overwhelming likely given the recent decline in TIPS spreads, Fed funds futures rates, commodity prices, and a wide variety of other indicators. Today’s news brings just one more example:

General Motors Co. and Ford Motor Co.’s finance arms likely face multibillion-dollar losses linked to the dramatic drop in used-vehicle prices, JPMorgan Chase & Co. analysts said.

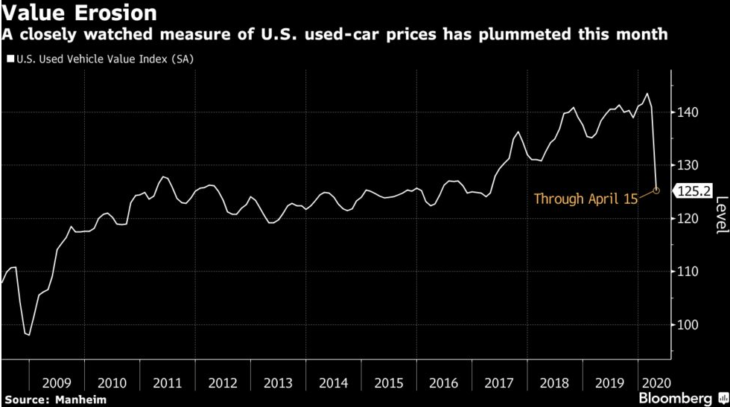

Prices are falling faster and steeper than JPMorgan was expecting, lead analyst Ryan Brinkman wrote in a report Monday, citing mid-month data from Manheim. The auto-auction firm’s closely watched used vehicle value index plunged 11.8% in the first 15 days of April, a decline that will easily set a record if it holds for the full month.

Instead of endless bailouts of companies, how about a monetary policy that prevents deflation from making the problem much worse?

Notice how the plunge looks even worse than 2008-09—a demand shock period!

Some false arguments:

1. “Properly measured inflation has actually risen, as the cost of buying many products (movies, restaurant meals, etc.) is now near infinity.” That may be true, but when thinking about monetary policy what matters is not “properly measured inflation”, it’s the nominal price of goods and services actually being sold. That’s the number you’d like to stabilize if you are a monetary policymaker that favors inflation targeting. We don’t target inflation at 2% because we believe that figure accurately measures the size of a raise you’d need to hold utility constant, we stabilize inflation at 2% because we believe this would tend to stabilize debt and labor markets. Movie theatre owners cannot repay nominal debts with infinite-priced tickets that never get sold.

2. “This isn’t really a supply shock, it’s a demand shock as people are unable to shop. So prices should fall.” This is a common mistake. A supply shock is a situation where RGDP growth will fall if you hold NGDP growth constant. So this is definitely a negative supply-shock. One mistake here is to conflate microeconomic-style supply and demand models with macro AS/AD models, which are totally unrelated. There is no “natural” or “free market” aggregate price level when the government has a monopoly on producing the medium of account (dollar bills and bank reserves.) The rate of inflation is whatever the Fed wants it to be, and it is certainly the case that disinflation at the moment would be a really bad outcome, something the Fed should do its best to avoid.

The Fed may currently be trying to avoid disinflation, but they aren’t trying hard enough. At a minimum, then need to institute level targeting ASAP. Then they need a “whatever it takes” approach to asset purchases, with a focus on buying safe assets.

I’m not too concerned with the April CPI, which will probably be as weak as March. My concern is that inflation in 2021 and 2022 is also likely to be weak. If so, that’s a big problem, a major policy failure.

READER COMMENTS

Thomas Hutcheson

Apr 20 2020 at 2:14pm

Granted that a 2% PL target is better than what we have a present, why not call for PL targeting at whatever higher level you think it should be. Or, if you do not have enough information to suggest a level, suggest a procedure for choosing that level. For example the Fed ought to be able to make an estimate of the size of the supply shock and set a PL target for x months in the future (and announce it in terms of the CPI so that it could be monitored by the TIPS spread) that would imply NGDP growth at 4%-5%. Or maybe you have a better idea.

Scott Sumner

Apr 20 2020 at 2:28pm

A higher price level target is even more politically difficult than a shift to NGDPLT.

Thomas Hutcheson

Apr 21 2020 at 7:49am

Maybe, but a shift to NGDPLT is not feasible right not without a NGDP futures market. How would the constraint work? Outrage when the Fed announced it was aiming for 2.5% inflation over the next x years and in fact front loaded it over the first 24 months? Or what if it just started doing it without an explicit announcement beyond some standard central bank gobbledygook about supporting recovery or promoting credit availability to small business?

Anyway, why not make the optimal recommendation about procedure for managing PL (combined with the creation of the NGDP futures market) and let the Overton Window take care of itself? 🙂

Scott Sumner

Apr 21 2020 at 1:19pm

I do have lots of papers out advocating NGDPLT. But I disagree that it requires a futures market. That would be nice, but it’s not essential.

Thomas Hutcheson

Apr 22 2020 at 9:34am

I do not disagree that the Fed could do NGDPLT without a futures market, but how could it be held accountable without one. That is why I think the alternative right not is to announce a CPI PL target that is enough greater that CPE 2% pa, to approximate NGDPLT. That is something that can be monitored ex post each month and ex-ante with the TIPS.

John Hall

Apr 20 2020 at 2:28pm

On #2, I’m a little skeptical that it is a supply shock. I recall one Mr. Scott Sumner arguing that nominal vs real shocks are easier to think about than demand vs supply shocks. We know that NGDP expectations fell significantly for 2020. This is a nominal shock, for sure. In this framework the impact of the real shock on RGDP could be found by estimating the change in Real GDP that is not explained by falling NGDP (for instance if you regress changes in RGDP on changes in NGDP and get the residuals). A similar arguing can be made for PGDP.

Scott Sumner

Apr 20 2020 at 2:51pm

I’m fine with calling it a “real shock”, indeed that’s better terminology than “supply shock”. But the analysis is the same—inflation should rise.

Garrett

Apr 20 2020 at 2:53pm

If this isn’t a supply shock then “supply shock” has no meaning.

Daniel

Apr 20 2020 at 5:02pm

I felt like this was a supply shock that has given way to a huge demand shock. But Dr. Sumner thinks this is all supply shock that “looks like” a demand shock because of the monetary policy response. I might be missing something, but it doesn’t make a lot of sense to me to suggest that the Fed here has not just been unwilling to fully avoid disinflation, but has even been offsetting the inflationary shock and then-some to produce the mild disinflation we’re seeing.

If the Fed’s monetary operations implied a just-right/semi-tight stance pre-crisis (with inflation coming in just under target), then as the crisis unfolded, simply maintaining those operations would imply a very-tight stance. The Fed’s operations changed, maybe not enough, but certainly to be looser than if they had “stayed the course.” If this is a policy mistake that implies mild disinflation, it would appear to me that the counterfactual of non-intervention would imply a policy disaster of deflation, the opposite of what the all-supply-shock story would argue, but consistent with what we’d expect from a demand shock (and with what we’ve seen in inflation expectations).

Maybe what I’m missing is that I’m thinking of this as AS or AD curves moving, and Dr. Sumner’s re-definition of a supply shock as a decline in RGDP even with constant NGDP perhaps implies that a demand shock doesn’t necessarily result in a decline in RGDP as long as NGDP doesn’t decline. Though in this case it seems like real vs. nominal shock might be more descriptive. I would love to see a reply or post explaining this more.

Thanks as always for the food for thought.

Scott Sumner

Apr 20 2020 at 10:36pm

To the extent that there is a demand shock, it’s due to the fact that monetary policy is too tight to produce 2% inflation. It’s true that if the Fed had done nothing we’d have even lower AD, but that’s not the right benchmark. The Fed has various targets for its policy, and that’s how the policy should be judged.

Thomas Hutcheson

Apr 21 2020 at 8:04am

This is confusing. Surely it is a demand shock if a firm looks at the number of people dying and decides this is not the be time to build that new widget factory or a work from home consumer, fearing they too might be laid off down the line, decides not to remodel the bathroom right now. Both are shifts from a demand fore goods to a demand for safe assets. Whether this kind of decision, in the aggregate, results in lower nominal consumption or investment of course depends on whether the Fed has an NGDP target or not, but the demand shock exists independent of the policy response.

Scott Sumner

Apr 21 2020 at 1:20pm

A demand shock is a fall in nominal spending, not a fall in real output.

Thomas Hutcheson

Apr 22 2020 at 9:51am

Yes, and that fall can come from a change in consumer and investor behavior, whether that’s seeing financial markets behaving strangely as in 2008 or firms being closed by SIPOs. In both cases the Fed needed/will need to do something to restore NGDP to its targeted path. The difference is that more inflation will be required in a supply shock than a demand shock. [I’m discounting the possibility that everybody has such firmly fixed expectations of NGDPT targeting being achieved that no change in behavior occurs in response to the shocks.]

Thomas Hutcheson

Apr 22 2020 at 10:36am

Yes, and that fall can come from a change in consumer and investor behavior, whether that’s seeing financial markets behaving strangely as in 2008 or firms being closed by SIPOs. In both cases the Fed needed/will need to do something — anything it takes — to restore NGDP to its targeted path. The difference it seems is that more inflation will be required in a supply shock than a demand shock. [I’m discounting the possibility that everybody has such firmly fixed expectations of NGDPT targeting being achieved that no change in propensities to consume and invest occurs in response to the shocks.]

Philo

Apr 20 2020 at 4:06pm

Well said! Maybe they’ll ignore you, but a clear, forceful, cogent voice is harder to ignore.

Brian Donohue

Apr 20 2020 at 4:47pm

Excellent post. Preach.

Alan Goldhammer

Apr 20 2020 at 5:01pm

“Then they need a “whatever it takes” approach to asset purchases, with a focus on buying safe assets.”

They certainly can buy a whole lot of oil right now which is a very safe asset. the problem is there is no place to store it.

Mark Bahner

Apr 22 2020 at 7:51am

Yes, Louisiana Light crude oil today is at negative $35 a barrel.

Read ’em and weep (depending on your viewpoint)

Sem H.

Apr 21 2020 at 7:33am

I think central bankers should be more humble in thinking they can and should achieve specific numerical targets, such as the rate of inflation, the price level or nominal GDP. The economy is a highly complex system, in which many uncertain factors play a role. Think about human psychology, politics or disasters such as the corona virus. Experience over the past decade shows this. Switzerland tried to keep inflation above zero by limiting the exchange rate of the Swiss franc, but they had to give up in 2015. Japan tried to achieve an inflation target on 2%, but they failed even after 7 years of trying and buying half of Japan’s government debt.

In my opinion, it is more important that the price level or nominal GDP moves in the right direction from a long term perspective. In the short run there can fluctuations in prices of nominal GPD: that is normal in a market economy and this is a way for the economy to adjust. For example, the monetary authorities of Singapore and Taiwan don’t have a specific inflation target and inflation fluctuated wildly over the past 20 years: when commodities prices were rising in the years before the global financial crisis, inflation rates were above 5%. During recessions and when there was an oil glut in the mid-2010s, inflation could be as low as -2%. But on average inflation rates were around 1.5% and 1% respectively for Singapore and Taiwan, and the economy functioned well.

Scott Sumner

Apr 21 2020 at 1:23pm

You said:

“Switzerland tried to keep inflation above zero by limiting the exchange rate of the Swiss franc, but they had to give up in 2015.”

This is false; it did not have to give up in 2015. As I predicted in 2015, the Swiss made a mistake. Denmark decided not to revalue at the time, and in retrospect Switzerland clearly made a mistake in revaluing its currency upward. I have many old posts on this issue.

I do agree that some fluctuations in inflation are desirable, which is why I favor NGDP targeting.

jj

Apr 21 2020 at 10:56am

Good post. I was a critic thinking that we need more than 2% inflation, but as you point out, we’re on track for less, so a price-level approach effectively creates a floor instead of a ceiling.

I think we can overcome some objections to “magical” central bank by noting that although central bank can’t magically create jobs, it can magically destroy jobs. With the track record that monetary policy has, simply not destroying jobs might even look like creating them.

BC

Apr 21 2020 at 4:01pm

The 10-yr forward, 20-yr treasury rate was 1.52% as of Monday (4/20). That’s the implied forward rate from 30-yr (1.22%) and 10-yr (0.61%) treasuries. Presumably, the coronavirus and any cyclical phenomena like a recession shouldn’t effect expectations about what will happen between 10 and 30 years from now. Do long-term forward interest rates like these imply that the market expects some sort of permanent, structurally tight monetary policy? Either that, or permanently low real growth? Again, this is a 10-yr forward rate, which should presumably be insensitive to current, temporary events.

bill

Apr 22 2020 at 3:45pm

This pandemic episode highlights another reason to favor NGDPLT. It’s a much easier sell to the general public that you are maintaining NGDP right now, than to say “since RGDP is falling, we need a higher inflation target” even though it’s the same thing.

Comments are closed.