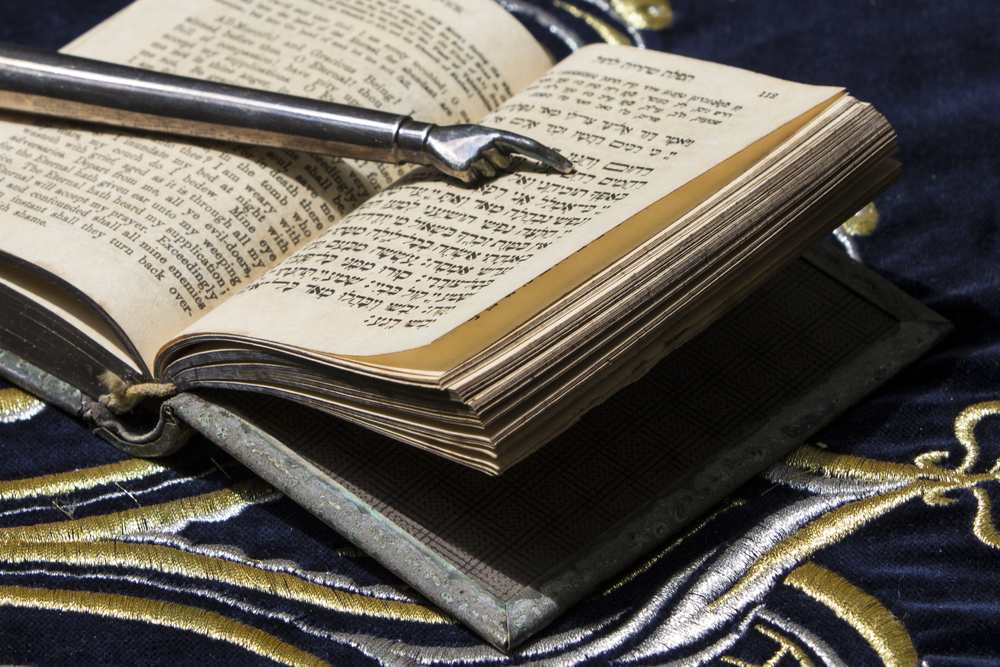

I’ve just read Berakhot, the first tractate of Talmud–the collection of rabbinic teachings from the first through sixth or seventh centuries C.E. And while the Talmud is known for its complex legal debates and the many lively tales interspersed among them, I have also enjoyed discovering the economic thinking it contains.

The first tractate of Talmud contains, for example, reminders to sell stock when demand is high. “When the horn is sounded in Rome, signifying that there is demand for figs in the Roman market, son of a fig-seller, sell your father’s figs, even without his permission, so as not to miss the opportunity.” (Berakhot 62a) * A discussion of when to say the blessing over a good fragrance leads to a digression on marketing–and possibly even positive externalities–when the rabbis consider whether the sweet smells that emanate from a spice shop are accidental or intentional. Berakhot 53a).

But the section of Berakhot that made me stop short was one that occurs when the Sages are discussing what blessing one should say when seeing a “multitude of Israel.” Several of the Sages say that the blessing should be “Blessed are thou…who knows all secrets” because this emphasizes the uniqueness of each individual within the multitude. But then we are told that the Sage Ben Zoma saw such a multitude and said not only “Blessed are thou….who knows all secrets” but also “Blessed are thought..Who created all these to serve me.”

This is a deviation from typical practice, so the Sages wonder why Ben Zoma does it. What does it mean to look out at hundreds of thousands of people and say that they were created to serve him? He explains:

How much effort did Adam the first man exert before he found bread to eat: He plowed, sowed, reaped, sheaved, threshed, winnowed in the wind, separated the grain from the chaff, ground the grain into flour, sifted, kneaded, and baked and only thereafter he ate. And I, on the other hand, wake up and find all of these prepared for me. Human society employs a division of labor, and each individual benefits from the service of the entire world. Similarly, how much effort did Adam the first man exert before he found a garment to wear? He sheared, laundered, combed, spun and wove, and only thereafter he found a garment to wear. And I, on the other hand, wake up and find all of these prepared for me. Members of all nations, merchants and craftsmen, diligently come to the entrance of my home, and I wake up and find all of these before me.

The Talmud doesn’t use the term “division of labor.” That’s added by modern commenters. But given that the term wouldn’t be coined for at least another 1000 years, the description of the power of the division of labor in this passage is remarkably apt. Ben Zoma even uses the still pertinent examples of food production and clothing production as his examples of the division of labor.

Reading Talmud merely for its economics would be an insult to the unimaginable richness of the text and its history. But reading it, one should absolutely be struck by the economic thought it contains, and by the fact that a deep understanding of important economic concepts can long pre-date the first appearance of the terms that contemporary economists use for them.

*All quotations are from the Koren Talmud Bavli, Noe Edition. Bold face type indicates English translation of the original Talmud. Plainface type is commentary and explanation by the editor of the edition, to aid in clarity.

READER COMMENTS

Yaakov

Mar 12 2020 at 3:26pm

When we studied that page, I emphasized the issue of division of labour. I also pointed out that the more people there are, the more plentiful and diverse is the stock of available merchandise and ideas.

For this last point like linking to this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ftXS8uJwL-Q

Comments are closed.