Bryan Caplan has a recent post on happiness and economic progress:

Seven years ago, my mentor Tyler Cowen did an interview with The Atlantic entitled, “Why I’m a Happiness Optimist but Economic Pessimist.” His point: Though GDP growth has been disappointingly low for decades, the internet does give us tons of free, fun stuff. The more I reflect on the Paasche price index, though, the more I’m convinced that Tyler’s picture is exactly upside-down. At least in the First World, the sensible position is economic optimism combined with happiness pessimism.

I’m with Bryan on happiness, although I can’t say I hold that belief with much conviction. I have absolutely no idea how happy I am (depends which day you ask me), so how could I possibly have an informed opinion on 7.3 billion people I’ve never met? All I know about other people is what I read in novels. And I don’t ever recall finishing a novel and thinking to myself, “that poor guy would have been happier if he’d been making $120,000/year rather than $80,000”. Their unhappiness comes from elsewhere. So call it a hunch—humans who already have the basic necessities to survive don’t get happier as they get richer.

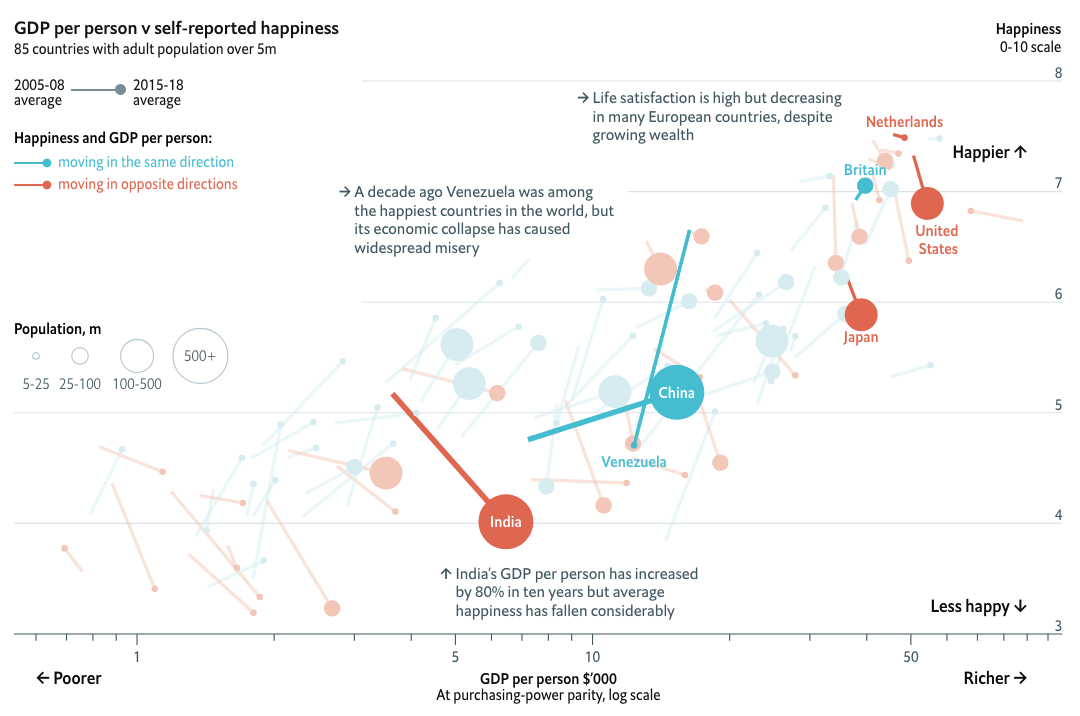

On the other hand, I certainly do believe that richer people are happier than poorer people, on average. Just as I believe they are healthier, on average. I suspect that some mysterious third factor explains both income and happiness. This would explain why, on average, countries do not seem to be getting happier as they get richer, over the past decade. From The Economist:

I’m not at all confident that the happiness survey data is accurate, but we have nothing else to go on.

I’m not at all confident that the happiness survey data is accurate, but we have nothing else to go on.

Actually, I’m surprised that the correlation between happiness and income is not more positive at the country level. While I don’t believe that higher income makes one happier, I do believe that the (free market) public policies that produce higher incomes make us happier. I’m far happier interacting with a private business than when I interact with a government bureaucrat, or an industry that exists due to regulation (i.e. health insurance.) At least private businesses have an incentive to make us happier in order to get repeat business. The DMV couldn’t care less whether or not I return to their office.

I’m an agnostic on economic growth because I don’t know how to measure it. Most stuff seems to be getting better over time, but how do we measure “better”? I suppose you could argue that growth is the extent to which new products like iPhones make us happier than old products such as party line telephones. (Millennials won’t remember those.) But even if new stuff makes us happier, when considered in isolation, it probably also generates the negative externality of making other stuff less enjoyable. If you are driving the equivalent of a 1965 Cadillac you probably feel miserable, as the car is a piece of junk. Everyone looks at you wondering why you are such a failure in life that you have to drive a car with a cheap plastic steering wheel, difficulty starting on cold mornings, and paint that rusts out after 5 years. But back in 1965 you felt great driving the same car.

Economic progress generates “better” stuff. While we can’t measure how much happier it makes us, it certainly has some value. But when you add in the negative externality of innovation making other stuff seem worse, it’s not clear that innovation has any net effect on happiness. I’m an agnostic on growth because I don’t know how to measure economic growth. The techniques we employ ignore the negative externalities from growth making the previous stuff seem worse than before. And yet, while we may not be growing we are certainly changing. We are good at inventing gadgets, but also good at inventing new ways to be unhappy.

When I take off my philosopher hat and put on my macroeconomist hat, I often insist that the economy has grown over time and that the living standard of average Americans is increasing. I am pushing back against the silly argument that millennials are worse off than their parents, in conventional terms. “The economy” is doing exactly what it’s supposed to be doing, generating higher living standards in the form of better stuff. If that’s not making us happier, that’s our problem. It’s not “the economy’s” problem. If happiness is not increasing over time it is because we are envious and insatiable. As the Chinese say, “Desire is a valley that can never be filled.”

PS. Now that I’m 63, I can look back on things that once seemed impressive but now are viewed as sort of lower class. Like 1200 square foot ranch houses:

READER COMMENTS

Mark

Apr 9 2019 at 3:26pm

Very interesting. I agree that the mental states of others are largely unknowable. For this reason, I think the best measure of happiness is revealed preference.

Revealed preference suggests that wealth as conventionally understood does increase happiness. For instance, almost everyone seems to prefer new stuff even though that may make them enjoy their old stuff less (and it’s quite possible that they would enjoy their old stuff less even if there was never any new stuff because novelty wears out by itself). And immigration flows almost always go from poorer to richer countries, as conventionally defined, suggesting that most people prefer to live in richer rather than poorer countries.

The free market vs. higher incomes point is interesting. As a libertarian, I definitely derive a lot of happiness from being in a free market, at least as much as I derive from higher income. But I question whether this is true for most people (of course, I am a middle-class American who has all basic necessities met and regular access to luxury goods; I might also value income over freedom were I a third-world peasant). For example, one interesting statistic I saw recently is that nearly all Chinese students in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s stayed in the United States, whereas today a majority go back to China. China is only a bit more free market today than then, but it is much wealthier. The fact that far more Chinese have a revealed preference to stay in China now suggests that the larger cause of unhappiness there was poverty rather than authoritarianism, and that unhappiness there has decreased significantly alongside economic growth.

Thus, from the perspective of revealed preference, I am both a happiness and economic optimist.

Scott Sumner

Apr 9 2019 at 6:02pm

Mark, Revealed preference is 100% consistent with my hypothesis that economic growth doesn’t make people happier. Think of the Cadillac example. No doubt the 2019 BMW 700 series is preferred over the 1965 Cadillac. But in 1965, that great quality BMW did not exist. It’s creation has reduced the utility of the 1965 car.

Moving from Guatemala to the US might make you happier, without growth in the US making existing Americans happier. After all, people born here are not progressing relative to their neighbors, on average

Mark Z

Apr 10 2019 at 1:07am

“Moving from Guatemala to the US might make you happier, without growth in the US making existing Americans happier. After all, people born here are not progressing relative to their neighbors, on average.”

But people moving from Guatemala aren’t either: in fact, they’re getting new neighbors that are comparatively much wealthier than them, certainly compared to their Guatemalan neighbors. Do you think immigrants mainly compare themselves with people from their home countries, or with people in the countries they move to? If the latter, the only difference between a Guatemalan moving to the US and an American experiencing growth in the US is that the latter is more gradual than the positive, sudden change experienced by the former.

I would argue that revealed preferences do in fact suggest people today value their lives than people in the past. I think people today are less violent, less belligerent, they take fewer risks (a few generations ago most planes didn’t even have seat-belts, let alone cars).

I think the fact that dirt poor people in the past were more willing to murder and pillage for bread than modern poor people are willing to murder and pillage for health insurance suggests that people who enjoy a similar relative position in the economy today are (if only subconsciously) appreciative of the fact that they are better off than their counterparts in past generations

Scott Sumner

Apr 10 2019 at 1:56pm

Mark, The people moving from Guatemala are psychologically comparing themselves to those who stay back at home. So they feel better off.

The argument about risk aversion is a good one, but could be due to longer lifespans and cultural change, not just higher living standards. Having said that, I do find your explanation to be plausible, people being more risk averse because they have more (utility) to lose.

Warren Platts

Apr 9 2019 at 4:58pm

A very interesting article Scott. Yes, I agree that growth is hard to measure. However, there is one metric that is objective, and does not lie: demographics. If the economy is performing as it should, then people’s life expectancies should increase. However, we are seeing life expectancies decrease. Death rates are up; birth rates are down by even more.

That is not a sign of healthy economy. As Ricardo said, a tight labor market is a happy labor market. In such circumstances, people live longer and can afford to have more children. In the opposite circumstance, Ricardo says that misery prevails, death rates go up, birth rates go down. That is what we are witnessing the USA now.

It is to the point where children are the new conspicuous consumption. Instead of buying 1965 Cadillacs, we buy 2019 children–if we can afford it. As for that “lower class” 1200 square foot ranch home, in a lot of places, such homes cannot be touched for less than $300K or even a million or more. A college education? You had better score in the 99th percentile of your SAT scores if your parents are not rich.

It is quite clear: real wages for the working class–the majority of the electorate–have gone down over the last 40 or so years. The demographics proves that is the case. And the obvious causes are free trade and mass immigration….

Scott Sumner

Apr 9 2019 at 6:08pm

Warren, As I recall, the world’s highest birth rate is Mali and the lowest in Singapore. What does that tell us about economic growth?

You said:

“As for that “lower class” 1200 square foot ranch home, in a lot of places, such homes cannot be touched for less than $300K”

Yes, like south central LA. But my point remains that this sort of house doesn’t seem as nice as it seemed in 1958. South central LA is considered lower class. There are a few areas where affluent people live in them (Silicon Valley) but that’s pretty unusual.

“It is quite clear: real wages for the working class–the majority of the electorate–have gone down over the last 40 or so years.”

Not clear at all.

Mark Z

Apr 10 2019 at 12:56am

“Not clear at all.”

Not only that, but demonstrably false. I think one can only get something like stagnant real wages (over the last 40 years, at least) by taking household income (and ignoring declining household size), ignoring non-monetary compensation, and making some other dubious decisions with the data.

Warren Platts

Apr 10 2019 at 4:02am

Not true at all. A decline in real wages will show up as a decline in the share of national income of workers as a matter of mathematical necessity. And that is exactly what is observed. If you take the fraction of GDP (or GDI–which is basically same thing) that the median worker earned in total compensation in 1979 (peak manufacturing employment) compared to now, it has declined by about 25%.

CZ

Apr 10 2019 at 9:26am

Real GDP per capita is twice as high today as in 1979 though. 75% of $60k > 100% of $30k.

It seems normal that as we get more technology, labor’s share of GDP would decrease. In a primitive world with no capital, all income would go to labor since there would be no way to generate production without labor. In the robot utopia, no income would go to labor since everything we need would be provided for without labor and people would spend their time at leisure. So a declining labor share of GDP is not a bad thing as long as per capita wages are increasing on an absolute basis.

Scott Sumner

Apr 10 2019 at 1:53pm

Labor share of national income is roughly the same as in 1965. GDP is not national income, it includes depreciation.

Warren Platts

Apr 10 2019 at 3:31pm

Hi Scott, I meant to include this FRED chart I constructed:

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=no6u#0

If you could take a look at it, the blue line is what the BEA puts out. They claim to take into account all compensation, and also proprietor income. The one caveat they include is that it also includes CEO, rock star and basketball star incomes. Yet it still shows a pretty significant decline in labor share.

Thus I tried to filter out the CEO effect by taking the median nominal earnings, and then dividing that by GDI (minus depreciation, though tbqh that has very little effect) per nonfarm worker. That shows (I think) that the median worker’s share of GDI/worker declined by 25% from 1980 to 2014, though it has bounced back a few pp in the last few years.

It could be I made a mistake there. If so, I wish someone would point it out because I don’t see it.

@CZ: Interesting hypothesis! But I suspect a more likely scenario is the Fed will push for full employment by goosing inflation in order to cut real wages without workers realizing it. As things get more expensive, every member of every household will be scrambling for work. And since wages will be so low, firms will not have to install robots; it will be cheaper to substitute human labor. The robot revolution will never happen. And thus everybody will get immiserated, including the rich. (Note to owners: your workers are your customers.)

Matthias Görgens

Apr 12 2019 at 8:15am

Of course, Singaporeans also manage to be uniquely unhappy. Despite living charmed lives.

Weir

Apr 10 2019 at 9:14am

Remember the Red Queen? “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place.”

The boomers, inspired by Alice in Wonderland, have made it their housing policy.

What’s unusual is that millennials in Tokyo, unlike millennials everywhere, aren’t being forced to run faster just to stay in the same place: “In Tokyo last year, housing starts came in around 145,000, according to Japan’s land ministry. This figure is on par with the total number of new housing units authorized last year in New York, Los Angeles, Boston and Houston combined, based on the U.S. Census Bureau data.”

Todd Kreider

Apr 10 2019 at 2:42pm

Caplan: “His point: Though GDP growth has been disappointingly low for decades, the internet does give us tons of free, fun stuff.”

Here are the average growth rates each decade up to the end of 2009:

1950s 3.9%

1960s 4.1%

1970s 3.5%

1980s 3.4%

1990s 3.0%

2000s 1.5%

Cowen was interviewed in 2012 so how could growth be disappointing low for decades when only one decade was low and included the worst recession in decades?

Cowen said in The Atlantic interview: “But it is still the case we’re planning and spending as if we’ll grow 2 to 3 percent [annually], and we might just grow 1½ percent. That is a disaster. We are not adjusting our expectations to the reality.

2010 to 2018 2.0%

Todd Kreider

Apr 10 2019 at 2:44pm

That should be 1 1/2 percent (1.5 percent)

Lorenzo from Oz

Apr 11 2019 at 7:40pm

Standard economic theory is happy with the insatiable, not so much with the envious. Ironic, since it is created by academics, who operate in a status-obsessed social milieu.

Dustin

Apr 15 2019 at 10:53am

I’ve always felt that “happiness” is primarily a function of outlook, with a bias towards the near-term, and wealth can be an indicator of outlook (but not always).

Comments are closed.