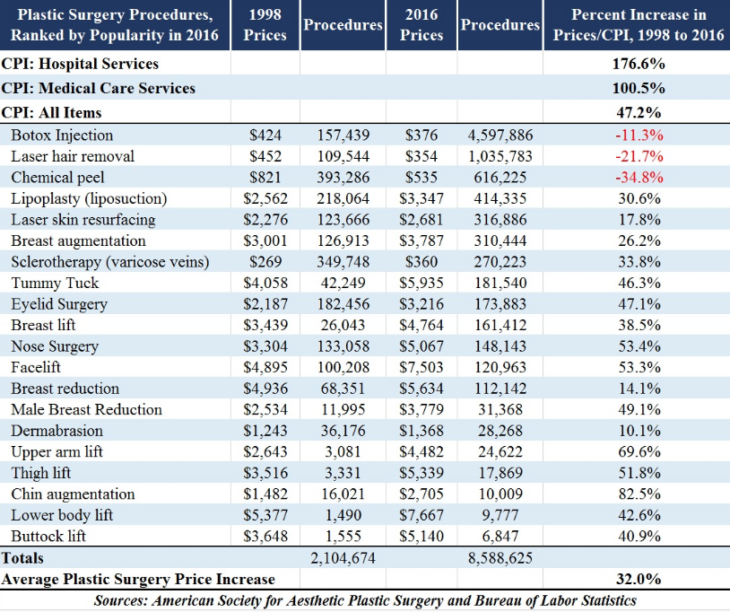

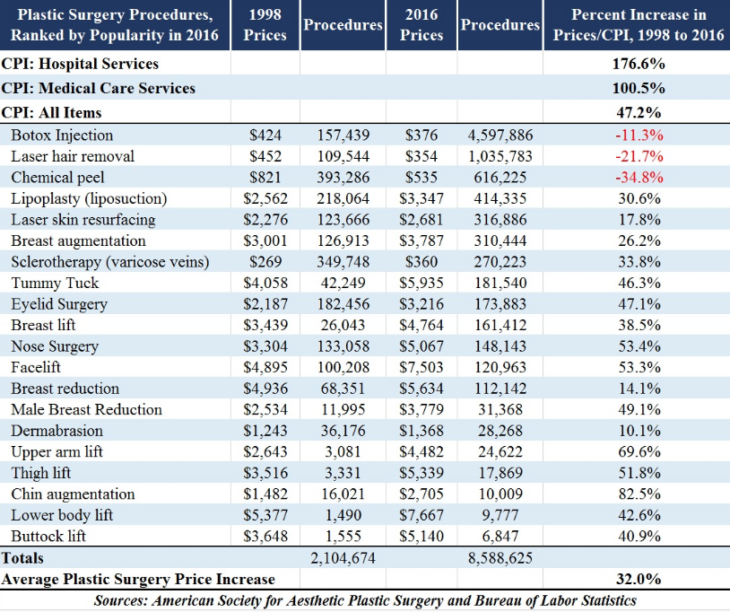

A couple of years ago, Mark Perry did an excellent post about prices in the health care industry. He presented a table that suggests the price of plastic surgery has risen much less rapidly than other medical costs:

I’m surprised by these results. To see why, consider the two big distortions in health care:

I’m surprised by these results. To see why, consider the two big distortions in health care:

1. The government imposes onerous regulations on health care, which one would expect to sharply boost prices.

2. The government massively subsidizes health care, which one would expect to sharply boost quantity.

Because expenditure equals price times quantity, these distortions would be expected to dramatically boost total spending on health care. Perhaps they do. So why am I surprised by the plastic surgery data?

As far as I know, plastic surgery is heavily regulated in ways similar to other forms of health care. There are tight limits on the ability of health care practitioners to migrate to the US from places where costs are far lower. And doctors in the US must undergo training far beyond the needs of the job. In addition, certain tasks that could be done by nurses are restricted to doctors.

Where plastic surgery differs from traditional health care is in the payment system. Plastic surgery is far less subsidized than other forms of health care, rarely covered by insurance. So if you think in terms of two distortions—subsidy and regulation—then it’s mostly in the area of subsidy where plastic surgery differs from other forms of medical care.

A priori, I would expect plastic surgery to cost about the same as other forms of surgery. I’d expect the biggest difference to occur in quantity, where plastic surgery would be done at close to the optimal level, while other forms of health care get provided at levels far beyond the optimum due to subsidies. In fact, it seems like the subsidies also impact price, indeed quite dramatically. This means that our health care regime might well be even more inefficient than it appears, with government subsidies boosting both price and quantity, while regulation further boosts price.

In other words, while the 32% boost in the price of plastic surgery trails the 47% rise in the CPI, and is far below the overall rise in medical costs, it seems plausible that even this modest price increase is excessive due to government regulation. In a truly free market in plastic surgery it is likely that prices would be far lower.

Bryan Caplan has a new post that discusses a recent book by Eric Helland and Alex Tabarrok. Bryan is not persuaded by their argument that the cost disease in health care and education is largely driven by the “Baumol effect” (rising wages in industries where productivity is stagnant):

So while Helland and Tabarrok are not wrong to invoke the Baumol effect, they are wrong to fail to blame government for dramatically amplifying it. If paying customers bore the full financial burden of education and health care, prices could easily fall by 50% or more.

In conversation, Alex objected that the growth rate of health care prices did not dramatically increase after Medicare was adopted. This would be a reasonable objection if my story were speculative. But “spending hundreds of billions of extra dollars a year on anything will make it much more expensive” is anything but speculative. Indeed, it’s virtually bulletproof; are we really supposed to imagine that the supply of health care is perfectly elastic despite a thicket of licensing requirements?! If prices did not grow more rapidly after the adoption of Medicare, the sensible inference is that price growth would have slowed if Medicare hadn’t happened. “Unfalsifiable”? No, but it is an application of a general principle so well-established that it’s crazy to doubt it now.

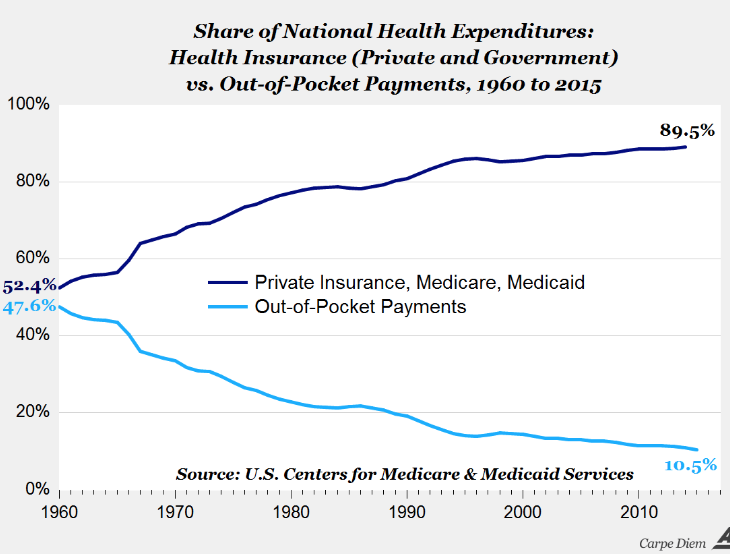

I haven’t yet had a chance to read their book, so I’ll reserve judgment on the relative importance of the Baumol effect. (I suspect they are broadly correct for the service sector as a whole.) Here I’d like to comment on the adoption of Medicare in 1965. The following graph in Mark Perry’s post suggests that Medicare’s impact was less significant than one might have suspected:

Private health insurance is heavily subsidized by our tax system. Once people are pushed into using insurance (by any means) to pay for expenditures, they have far less incentive to economize on purchases. This was already a problem even before Medicare was adopted in 1965. In my own life and the lives of people I know I see frequent examples of large health care expenditures that only occur only because private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid are picking up the bill. That fact doesn’t mean these government subsidies increase prices, merely that they boost quantity (and hence expenditures.) But if we combine the gradually increasingly level of government subsidies with the data on plastic surgery prices, I suspect that subsidies are increasing both prices and quantity in the health care industry.

Private health insurance is heavily subsidized by our tax system. Once people are pushed into using insurance (by any means) to pay for expenditures, they have far less incentive to economize on purchases. This was already a problem even before Medicare was adopted in 1965. In my own life and the lives of people I know I see frequent examples of large health care expenditures that only occur only because private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid are picking up the bill. That fact doesn’t mean these government subsidies increase prices, merely that they boost quantity (and hence expenditures.) But if we combine the gradually increasingly level of government subsidies with the data on plastic surgery prices, I suspect that subsidies are increasing both prices and quantity in the health care industry.

I suspect that health care is the single biggest factor explaining mediocre wage growth, with education subsidies a close second. The left focuses on redistributing wealth from the rich to the other 99%, but the biggest need is to reduce the bloated spending levels in health care and education, which is massively inflated by subsidies and regulations. This would free up enormous resources to produce more housing, tourism services, and other goods of real value to average Americans. To conclude:

1. Basic economic theory predicts that our system of subsidy and regulation would produce vastly excessive spending on health and education. If not, then much of the EC101 taught in principles textbooks is flat out wrong.

2. All of the empirical studies I’ve seen suggest that there is little or no evidence that this extra spending produces significant gains.

The burden of proof is on those who favor trillions of dollars in government subsidies for health care and education. So far they are not even close to meeting that burden.

READER COMMENTS

Benjamin Cole

Jun 12 2019 at 8:56pm

Probably healthcare, education and along the West Coast, NY and Boston, exploding housing costs explain stagnant real median weekly wages in the US since 1978 (the FRED chart mercifully does not extend back before 1978 so we do not know if real weekly median wages have been stagnant since, say, the late 1960s or 1972).

The Federal Reserve’s squeamish hysteria regarding “tight” labor markets may have also played a role in suppressing wage incomes, as has a de facto open borders policy for illegal immigration.

There are certainly free-market solutions to housing costs, starting with the total elimination of property zoning and the reaffirmation of development rights for property owners.

Other nations seem to get the same results from health care but for half the cost, unfortunately those nations go to socialism to obtain that result.

In the US, the VA claims to provide health care at the same cost as the private sector through publicly owned hospitals, staffed by federal employee doctors, nurses and administrators. Indeed, the entire US military operates hospitals for millions of federal employees, and no one suggests reforming that system.

An interesting experiment would be to privatize US military hospitals and see if cost-savings actually emerge.

Alan Goldhammer

Jun 13 2019 at 9:03am

Ben Cole writes, “Other nations seem to get the same results from health care but for half the cost, unfortunately those nations go to socialism to obtain that result.”

This is not true. There are a number of countries that use regulated insurance markets to provide coverage for their citizens (Netherlands, Germany, & Switzerland). Go read TR Reid’s book, “The Healing of America: A Global Quest for Better, Cheaper, and Fairer Health Care” where he surveys a number of foreign countries systems where he had care during his time as a foreign correspondent for the Washington Post. Highly informative and a quick read. It will dispel a lot of the misconceptions that I often see posted on this and other blogs.

Benjamin Cole

Jun 13 2019 at 8:01pm

Alan G— well, provide a synopsis for us.

Alan Goldhammer

Jun 14 2019 at 12:26pm

Seriously?? The book is under 300 pages with relatively large type and it’s a quick read. There is a Wikipedia page for the book which isn’t much but it does link two reviews. The Kindle version is just under $10 so it won’t bankrupt you the way new Econ textbooks will.

travis allison

Jun 12 2019 at 10:04pm

Veterinarian prices seem to have increased at a rate greater than inflation and I don’t think they are subsidized in general. The following article has a bit on that.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2015/04/21/vets-are-too-expensive-and-its-putting-pets-at-risk/?noredirect=on

Scott Sumner

Jun 13 2019 at 1:19pm

Travis, Yes, but they are extremely tightly regulated, with the supply of veterinarians being held down far below demand.

travis allison

Jun 14 2019 at 2:09pm

Perhaps, but is the supply of vets more restricted than plastic surgeons? My guess is no, because plastic surgeons have to do a residency in addition to all of their years of education.

I’d be interested in seeing the salary history of plastic surgeons over time. My guess is that it has increased at about the same rate as other medical professionals. So perhaps something else explains the drop in prices for plastic surgery. Has it become a lot more efficient for some reason due to improved techniques? This seems like a good topic for someone to research the *detailed reasons* for the price differences compared to other medical procedures. We might learn a lot.

Benjamin Cole

Jun 13 2019 at 3:59am

Here is a laugher on education costs, from Tyler Cowen—

“Typically a university is investing large sums of money to make those students employable and successful, usually on the academic market; the University of Chicago says it invests more than $500,000 per doctoral student.”

—30—

Remember, that $500,000 bill does not include undergraduate costs….

Is a rough guess that it costs $1 million to give someone a PhD?

But there was 12 years of schooling before the student even got into college.

What if we pay people $100,000 not to go to college?

Alan Goldhammer

Jun 13 2019 at 9:00am

I serve on the Board of a non-profit associated with a large Federal biomedical research institution and one of its functions is to provide health insurance to research fellows who are not permanent employees and do not qualify for the normal health insurance policy. We self insure and try to keep underwriting costs as low as possible. Having looked at costs over the past five years (two of which were in the red), the biggest drivers of cost are premature births and specialty pharmaceuticals. There are about 6K individuals under the policy (both single and family units) and the age cohort of the research fellows is on the young side.

Some new pharmaceutical treatments for rare medical conditions now cost $700K/year and we have seen costs for a premature birth and resulting care in the neonatal intensive care unit quickly reach $200-500K depending on the length of stay. We do have stop loss insurance that covers medical care but not pharmaceutical treatment.

From my perspective, things are not nearly as simplistic as Helland and Tabbarok make them out to be. I wish that more economists would go into real life situations and see how things work.

Scott Sumner

Jun 13 2019 at 1:21pm

I don’t think they deny that expensive new technologies have been invented.

Alan Goldhammer

Jun 13 2019 at 1:51pm

I’ve read the piece and of course they comment on technology improvements. I was only pointing out to major cost drivers in a small population that I know about. Rx utilization has been constant over a period of five years of data that I have looked at but cost have increased dramatically. Generic drug utilization is at 83% with the rest coming from on-patent drugs. Biologics make up a significant portion of the on-patent drug use and those prices are extremely high and increasing faster than the rate of inflation. Part of this results from a marked slow down in R&D from some pharma companies and they now have fewer products that provide significant revenue streams.

Mark Z

Jun 13 2019 at 7:03pm

I’m not sure this is inconsistent with their Baumol effect story. As people live longer and get sicker, demand for healthcare goes up, and new products/services get increasingly more sophisticated and expensive, while returns to investment decline. It was far easier and cheaper to develop new antibiotics or early cancer therapies decades ago that could save millions of people per year than it is now to develop new therapies that can save even a few thousand. Tragic, but diminishing marginal returns are present with most goods and services.

Alan Goldhammer

Jun 14 2019 at 12:28pm

As I noted, these are not “old” people. They are research fellows in their mid-20s to late 30s. The biggest cost drivers we see are pregnancy related care pre and post natal and the use of specialty biologics for a number of different medical conditions.

Phil H

Jun 13 2019 at 9:48am

“Basic economic theory predicts that our system of subsidy and regulation would produce vastly excessive spending on health and education. If not, then much of the EC101 taught in principles textbooks is flat out wrong.”

I do like a nice, bold statement! I know healthcare spending in the USA is higher, but in Europe is mainly contained to within 10% of GDP, as I recall. 10% of what we produce used on keeping people alive? That doesn’t feel “vastly excessive”… I know, feelings don’t count for much but still. Maybe Ec101 is all bunkum!

“The burden of proof is on those who favor trillions of dollars in government subsidies for health care and education.”

The problem with this is how it sounds like that joke about the French. “I know it works in practice, but does it work in theory?” Every developed nation in the world does this. In the courts, where the words “burden of proof” actually mean something, you’re not allowed to lock someone up until you meet the burden of proof. Those who favour massive regulation and subsidy have already got this one locked up.

Scott Sumner

Jun 13 2019 at 1:24pm

Phil, How much of health care spending is focused on “keeping people alive”?

You said:

“Every developed nation in the world does this.”

Really? We spend 17% of GDP and Singapore spends 5%. Are they not developed?

Mark Z

Jun 13 2019 at 7:13pm

The problem is you’re looking at the wrong metric. Consumption, rather than GDP, is what mainly predicts healthcare expenditure and quantity, and when you look at it in terms of average per capita consumption, US is very close to the trend line (I’d check out the recent posts on randomcriticalanalysis for the plots illustrating this), so no, other countries that spend trillions and heavily regulated their markets haven’t got it ‘locked up.’ That’s a particularly bizarre statement since the US is one of those nations. The idea that we have some generally less regulated, less subsidize, laissez faire free market healthcare system is pure fantasy. Out of pocket + private insurance only makes up about 40% of health care expenditure in the US, and private health insurance is heavily subsidized and regulated. What’s more, even if we pretend the US system contrasts with most European countries in ways it doesn’t really, when one compares average Medicare costs (our biggest single payer system), we find that the ratio of average Medicare costs to what other countries spend on their >65 population is comparable to the ratio of what the US spends on average compared with what other countries spend on average (this I’m recalling from Arnold Kling’s book, Crisis of Abundance, I forget the source he refers to).

Johnson

Jun 13 2019 at 11:12am

I think you are ignoring the fact that government regulation basically prevents the quantity for rising. The number of doctors available are basically capped by the number of med school spots and more importantly, the number of residencies. There’s not much labor saving investment they can make; only more support staff to let doctors focus entirely on seeing patients and not on work not requiring a medical license. The only real influence price has on quantities is how much and for how long doctors work rather than retire, and that’s a mixed bag b/c while higher income makes it more attractive to doctors to work longer hours or delay retirement, it also makes retirement or shorter hours more appealing b/c the wealth effect makes it more likely that they will choose more leisure over more income.

So with plastic surgery not being subsidized nearly as much, it could reduce quantities by plastic surgeons choosing other medical fields (which is I believe limited by competitiveness of residencies and specializations, although I guess they are all already qualified to be general surgeons?). I think a large reason you don’t see that is that there is so much administrative cost to dealing with insurance, that their income doesn’t really lag behind doctors that are heavily reliant upon insurance payments.

Scott Sumner

Jun 13 2019 at 5:05pm

I do believe that quantity is also increased, despite regulation. The US is known for doing lots of procedures that are not medically necessary. Regulation makes supply less elastic, but not perfectly inelastic.

TMC

Jun 13 2019 at 3:08pm

Good call on linking this back to Mark Perry’s work. You are likely right. I’m glad the number of procedures was listed as well. My first thought was that plastic surgery wasn’t nearly as a mature industry as the rest of medicine, so it would benefit from new processes. The procedure numbers show that’s not the case.

Jeff Hallman

Jun 17 2019 at 2:08pm

Plastic surgery seems better suited to medical tourism than most other kinds of medical care, so that probably limits how much domestic plastic surgeons can charge. Also, since insurance is often not involved, patients price-shop. In the long run, you would expect these factor to result in plastic surgery largely moving overseas, lower compensation for domestic plastic surgeons, and ultimately fewer domestic plastic surgeons.

It is insane that Medicare, the primary funder for medical residencies, funds no more of them now than it did 30 years ago. Most of us understand that restricting supply creates shortages and higher prices, but we seem to forget that when we discuss things like housing and medical services.

Comments are closed.