As promised last month, I’m posting Charley Hooper’s and my latest op/ed in the Wall Street Journal. This is number 61 for my lifetime WSJ op/eds and book reviews.

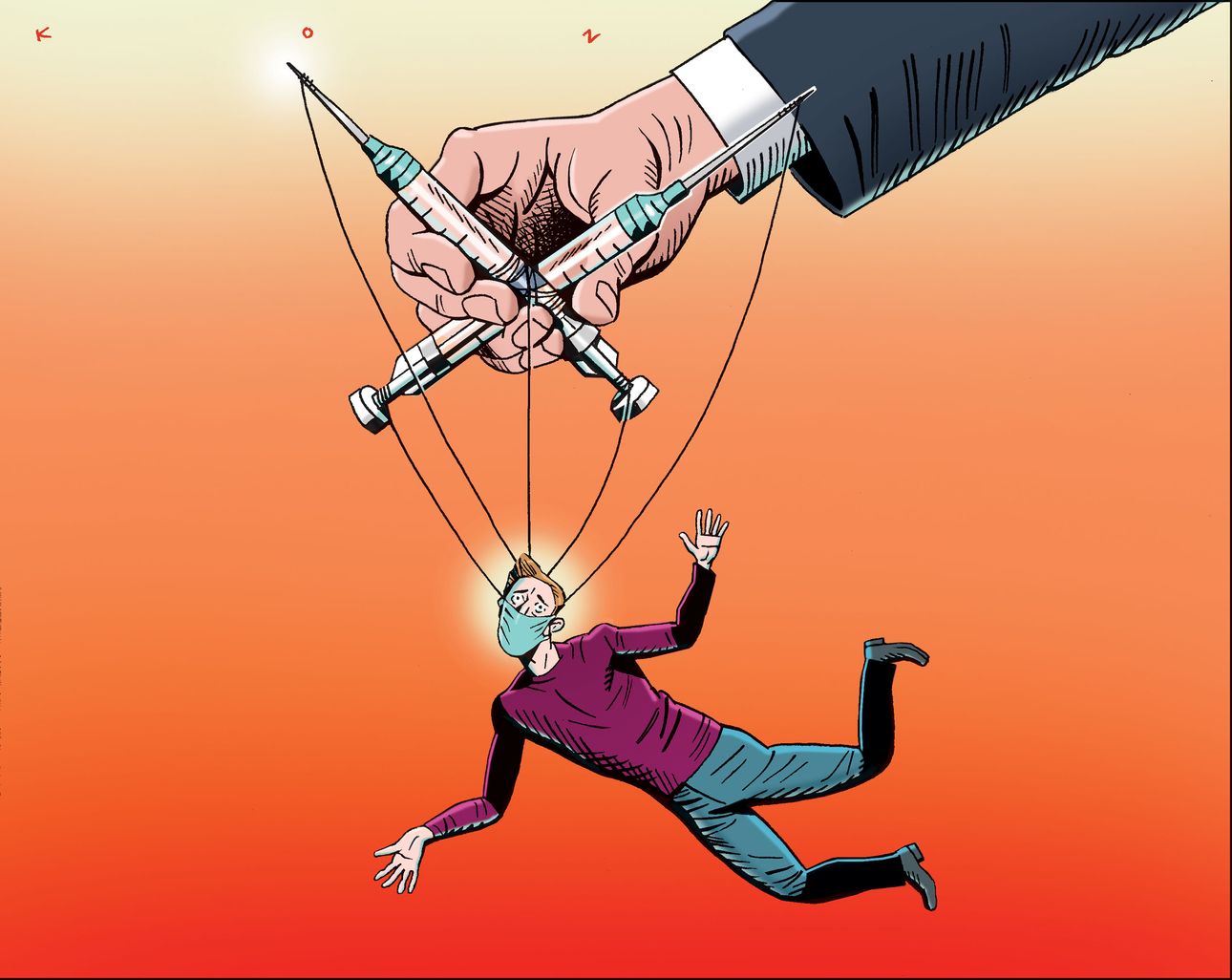

Coercion Made the Pandemic Worse

Freedom is the central component of the best problem-solving system ever devised.

By David R. Henderson and Charles L. Hooper

The online Merriam-Webster dictionary defines “anti-vaxxer” as “a person who opposes the use of vaccines or regulations mandating vaccination.” Where does that leave us? We both strongly favor vaccination against Covid-19; one of us (Mr. Hooper) has spent years working and consulting for vaccine manufacturers. But we strongly oppose government vaccine mandates. If you’re crazy about Hondas but don’t think the government should force everyone to buy a Honda, are you “anti-Honda”?

The people at Merriam-Webster are blurring the distinction between choice and coercion, and that’s not merely semantics. If we accept that the difference between choice and coercion is insignificant, we will be led easily to advocate policies that require a large amount of coercion. Coercive solutions deprive us of freedom and the responsibility that goes with it. Freedom is intrinsically valuable; it is also the central component of the best problem-solving system ever devised.

Free choice relies on persuasion. It recognizes that you are an important participant with key information, problem-solving abilities and rights. Any solution that is adopted, therefore, must be designed to help you and others. Coercion is used when persuasion has failed or is teetering in that direction—or when you are raw material for someone else’s grand plans, however ill-conceived.

Authoritarian governmental approaches hamper problem-solving abilities. They typically involve one-size-fits-all solutions like travel bans and mask mandates. Once governments adopt coercive policies, power-hungry bureaucrats often spout an official party line and suppress dissent, no matter the evidence, and impose further sanctions to punish those who don’t fall in line. Once coercion is set in motion, it’s hard to backtrack.

Consider Australia, until recently a relatively free country. Its Northern Territory has a Covid quarantine camp in Howard Springs where law-abiding citizens can be forcibly sent if they have been exposed to a SARS-CoV-2-positive person or have traveled internationally or between states, even without evidence of exposure. A 26-year-old Australian citizen, Hayley Hodgson, was detained at the camp after she was exposed to someone later found to be positive. Despite three negative tests and no positive ones, she was held in a small enclosed area for 14 days and fed once a day. Even the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says quarantine can end after seven days with negative tests. Why didn’t the government let her quarantine at home? And why doesn’t it exempt or treat differently people who can prove prior vaccination or natural infection?

Although U.S. authorities haven’t gone nearly that far, early in the pandemic the Food and Drug Administration used its coercive power to discourage the development of diagnostic tests for Covid-19. The FDA required private labs wanting to develop tests to submit special paperwork to get approval that it had never required for other diagnostic tests. That, in combination with the CDC’s claims that it had enough testing capacity, meant that testing necessitated the use of a CDC test later determined to be so defective that it found the coronavirus in laboratory-grade water.

With voluntary approaches, we get the benefit of millions of people around the world actively trying to solve problems and make our lives better. We get high-quality vaccines from BioNTech/ Pfizer, Johnson & Johnson and Moderna, instead of the suspect vaccines from the governments of Cuba and Russia. We get good diagnostic tests fromThermo Fisher Scientific instead of the defective CDC one. We get promising therapeutics such as Pfizer’s Paxlovid and Merck’s molnupiravir.

With authoritarian approaches, we get solutions that meet the requirements of those in power, regardless of how we benefit. Consider this hypothetical example:

Policy A ends with 1,000 Covid-19 cases, 5,000 people who have completely lost their liberty for two weeks, 1,000 lost jobs, and 300 missed key family events, such as the funeral of a loved one.

Policy B ends with 1,020 Covid-19 cases, 4,000 who have lost some of their liberty for one week, 1,000 who have completely lost their liberty for two weeks, 300 lost jobs, and 100 missed family events.

The government may prefer Policy A because it is focused on one aspect of the problem. You might prefer Policy B because many aspects of life matter to you—not only coronavirus cases—and B is much better on the other dimensions. But your preferences don’t count.

With coercive solutions, you’ll often deal with an official who will absolve himself of responsibility by pinning the rule on those giving the orders. With voluntary solutions, if it doesn’t make sense, we usually don’t do it. And therein lies one of the greatest protections we have to ensure that the solution isn’t worse than the problem.

The supposed trump card of those who favor coercion is externalities: One person’s behavior can put another at risk. But that’s only half the story. The other half is that we choose how much risk we accept. If some customers at a store exhibit risky behavior, then we can vaccinate, wear masks, keep our distance, shop at quieter times, or avoid the store.

Economists understand how one person can impose a cost on another. But it takes two to tango, and it’s generally more efficient if the person who can change his behavior with the lower cost changes how he behaves. In other words, to perform a proper evaluation of policies to deal with externalities, we must consider the responses available to both parties. Many people, including economists, ignore this insight.

By what principle do we throw out the playbook of the more successful country, ours, and adopt one from less successful, more authoritarian countries? The authoritarian playbook has serious built-in weaknesses, while solutions based on free choice have obvious and not-so-obvious strengths. Freedom is beneficial in good times; it’s even more crucial in challenging times.

Mr. Henderson is a research fellow with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. He was senior health economist with President Reagan’s Council of Economic Advisers. Mr. Hooper is author of “Should the FDA Reject Itself?” and president of Objective Insights, whose clients include pharmaceutical companies.

READER COMMENTS

JFA

Jan 30 2022 at 8:05am

“By what principle do we throw out the playbook of the more successful country, ours, and adopt one from less successful, more authoritarian countries?”

I guess this depends on what you consider “success”. If there is an action that takes collective action that you (and the vast majority) prefer, but someone else prefers an action that doesn’t take collective action, some coercion might necessary to achieve the most “successful” outcome. This is obviously a sticky issue that whole fields of political philosophy are dedicated to and hasn’t resolved.

I get the sense that the vast majority of Australians are satisfied with how the past couple of years have gone (relative to what other governments have done): https://poll.lowyinstitute.org/charts/global-responses-to-covid-19/.

Their policies weren’t necessarily available to the US, but I think many people would consider Australia and new Zealand to have achieved “success”, even if an authoritarian way.

Mark Z

Jan 30 2022 at 5:15pm

I think this is true, but it’s still consistent, from a utilitarian perspective, with the claim that Australian policies were objectively worse. An American who favors Australian policies can more easily impose such standards on himself voluntarily than an Australian who prefers American policies can escape the imposition of Australian policies, so, one can argue, you suffer less when your country is too lenient for your taste than when it’s too strict for your taste, meaning relative popularity doesn’t necessarily tell us which policy is more optimal. The best measure of that might be how many Australians move to the US vs. vice versa, if international travel weren’t itself largely suppressed as part of policy designed to deal with the pandemic.

Dylan

Feb 1 2022 at 6:39am

This doesn’t seem true on the face of it. The “success” of Australia’s policies were that they were very strict on a few (i.e. overseas travelers, people who came into contact with someone that might have had Covid, etc…) and because of this, they let the rest of the country live their lives pretty much normally. Going to restaurants, going to school, not masking up everywhere. If I, as an American, wanted to live that life in April of 2020, how would I have done so?

Semi-snarky answer is, move to Florida, which a bunch of people did. But, let’s say I wanted to live my life mostly normally without a vastly increased risk of catching Covid?

David Henderson

Feb 1 2022 at 10:55am

What’s your evidence that you would have had a “vastly increased risk of catching Covid” if you had moved to Florida?

Dylan

Feb 1 2022 at 12:28pm

I’m comparing living in Florida to living in Australia in the early part of the pandemic. Both have roughly similar populations (21m in Florida vs. 26m in Australia). By the end of 2020, Australia had recorded less than 30,000 Covid cases while by June 1st, 2020 Florida had recorded more than 20x that number. Apologies for the mismatched time frames, hard to find perfect matches. But, hopefully illustrative of the point that your chance of getting Covid in 2020 was much higher in Florida than in Australia (I’m limiting it to 2020, because my understanding is that Australia started liberalizing some of the travel policies towards the end of 2020 (a colleague was able to return home to Australia somewhere around that time if I remember correctly). Even today, taking a look at deaths, Australia has about 3,800 and Florida has over 60K.

This isn’t to suggest that Florida’s policies were bad, or Australia’s were good. I just took exception to Mark’s claim that if you wanted Australia’s policies in the U.S., you could have them. That seemed to suggest to me that he thought the policies were centered around strict lockdowns as opposed to relatively free movement of the population at home and extremely restrictive ability to travel.

It’s also true that the U.S. as a whole likely didn’t have the ability to take the steps that Australia did, even if we wanted to. The virus was already way too established by the time we went into lockdowns and even if it wasn’t, it’s much harder to restrict travel here than it is on a big island. All I’m saying is “An American who favors Australian policies can more easily impose such standards on himself voluntarily than an Australian who prefers American policies can escape the imposition of Australian policies” doesn’t seem true to me, at least not how I read it. I’d appreciate clarification on what Mark meant.

Mark Z

Feb 1 2022 at 2:52pm

I think Australia’s covid policies were much more stringent than that for much of the pandemic (at times when they were still less stringent than that in most of the US). Moving to Florida is still likely more difficult than living according to Australian rules where you are, and even that option depends on covid policy being left almost entirely to the states (I know in Australia this is largely true too, but there seems to be much more homogeneity among the regional governments’ response than in the US).

Dylan

Feb 1 2022 at 4:43pm

I stand corrected. I was relying on reports from friends in Australia who reported things were mostly open in the early stages of the pandemic, as well as the interview with Tyler Cowen on Covid policies, where I thought he said the same thing. However, reading the Wikipedia page on Australia’s Covid resposne suggests things were, at least officially, much stricter than that. I know in New York at least, the official policies at the height of the pandemic and the actual way people behaved diverged a fair amount, so maybe that was the case in Australia as well? Nevertheless, I apologize for relaying incorrect information.

David Henderson

Feb 1 2022 at 10:02pm

Dylan,

You’re a good man.

Dylan

Jan 30 2022 at 9:46am

Last sentence of the 2nd paragraph appears to be truncated

This is horrible if true, but I’m a little disinclined to take this at face value without corroborating accounts. It’s the story from just one person and the accounts I’ve seen were all very one sided. I don’t doubt that an authority figure would tell her that she has to obey even if the laws don’t make sense…but I’m a lot more skeptical of the only fed once a day thing, unless that means something like she gets groceries delivered once a day and makes her own meals, or something like that.

Now on to the meat of my comment. I agree that it is good to distinguish between persuasion and coercion, but also important to acknowledge that these are not binary attributes but exist along a continuum.

Take examples from outside our Covid policies. Is it coercion to opt someone in by default to the 401K plan as long as they have the option to opt-out? Is it persuasion if I ask a young actress out on a date where they are free to say no, but I’m a powerful movie executive and if they say no they worry that I might make it difficult for them to get cast in any big movies? Is the bank forcing me to buy a cell phone plan when they (and all of their competitors) won’t let me authenticate without receiving an SMS verification code?

Reasonable people can disagree with what counts as coercion and what is merely strong persuasion. They can also disagree on the circumstances under which coercion is justified. Personally, I’m closer to your side than that of the restrictionists. I agree when you say that authoritarian approaches hamper problem solving abilities (whether government or corporate or cultural) and more freedom would lead to more efficient ways to minimize the harms of Covid.

However, I think you minimize the externality story more than you should by focusing on the least cost avoider, in fact I think this somewhat contradicts your point on Australia. For most of the pandemic, the average Australian has had far more freedom to go about their lives normally than the average American, and certainly more than the average European. Yet, the way they did this was by severely hampering the freedom of a small percentage of people, like those Australians that happened to be overseas when the pandemic struck and those like Ms. Hodgson. Alternatively, they could have preserved the freedom of travelers and others, and let the remaining people choose the level of risk they wanted to assume. Those at high risk of death would be free to continue to live normally if they wanted a high risk of getting infected, going to the hospital, and possibly dying. Is this persuasion or coercion?

Jon Murphy

Jan 30 2022 at 11:41am

Dylan-

Coercion has a pretty precise meaning: when one’s actions are the result of other people’s choices and not their own. Consequently, we can easily parse your hypothetical questions:

-The 401K plan is not coercive. The individual has the right to opt out at any time, regardless of what other people want.

-The bank is not coercive as you have the option to not tele-bank, and any competitor could come along and offer you the non-SMS option. No one is forced to do anything.

The actress example needs clarification. You write: ” they [the actress] worry that I [the executive] might make it difficult for them to get cast in any big movies?” That statement is vague. Why does she worry? If it is known the executive behaves in such a manner, then it is coercive. If she merely has an overactive imagination, then no.

I don’t think the topic is as ambiguous as you want it to be. Liberty does not imply doing whatever we want, nor does it guarantee happiness. Actions have consequences and actions have costs. The fact that the 401K has a default of opt in, or that your bank requires an SMS, is no more coercive than the fact the grocery store charged me $4 for steak today. For an action to be coercive, you need to point to a person imposing their will on another unwillingly. In two of the three examples, you failed to do that. On the third, it’s ambiguous (not because of ambiguity between coercion and persuasion, but because of the ambiguity of the question posed).

Dylan

Jan 30 2022 at 1:27pm

Argh, third time trying to post this. I’ll try to be briefer this time.

First, I don’t think that moral philosophers or the general public agree with you that there is such a clear distinction between persuasion and coercion. I wouldn’t normally quote Wikipedia, but this passage from the article on coercion is relevant.

Second, I think a large component of coercion is subjective to the person being coerced (or persuaded). If you hold a gun to my head and threaten to kill me if I don’t do X, but I’m highly suicidal and was planning to kill myself later that day, have I really been coerced to do X? What if I’m terrified of social exclusion and I know that if I don’t do Y my friends will never speak to me again. Am I being coerced to do Y?

And, I think the ambiguity is key, because life is ambiguous. The actress may have heard rumors about the movie exec and believing them, feels coerced to going out with him. But, the rumors might be totally false. Does that change the coercion? From the moral culpability of the exec, it seems obvious it does (although I think plenty of people would disagree with me), but from the perspective of the actress, it doesn’t seem to meaningfully change things.

David Henderson

Jan 30 2022 at 5:49pm

Dylan,

Thanks for catching the mistake. I updated.

I agree with Jon Murphy on 2 out of 3 of your examples he responded to.

I don’t agree on the movie executive one. You ask:

Yes. The key is that, as you recognize, the actress is free to say no.

Dylan

Feb 1 2022 at 12:36pm

We’re always free to say no. There’s just a range of consequences that can stem from refusal. At one end, that could be death or torture of you or a loved one. On the other end, it might just be you feel uncomfortable for having to say no. In the middle there can be all sorts of consequences; physical, economic, social. What level those consequences have to rise to to be considered coercion instead of persuasion is what I was trying to get to. I don’t think you’ll find anything close to universal agreement on that. Look at the MeToo movement and the number of cases where it is agreed that a man had gotten verbal consent, but it was later deemed (at least by a subset of the population) that given the power imbalance the women was coerced and not in a position to truly consent.

Scott Sumner

Jan 30 2022 at 12:59pm

I agree with much of this post. But I slightly disagree here:

“Consider Australia, until recently a relatively free country.”

Australia is still freer than the US in an overall sense, despite some misguided Covid policies.

Mark Brophy

Jan 31 2022 at 8:35pm

Australia’s Covid policies are so bad that states like Florida and about 20 others are more free than Australia but some our worst states such as New York and Hawaii are worse than Australia.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jan 31 2022 at 6:04am

I just find the cost benefit framework better for discussing these issues. DFA’s hostility to tests, failure to accelerate vaccine development, closing parks, etc. are just mistakes in the use or failure to use cost benefit analysis of those policies. Ditto vaccine mandates. The costs of vaccination to the person vaccinated is infinitesimal compared to the cost of everyone else avoiding contact with them. Both sides-ism does not usually very much affect the conclusion of anti-externality measures (taxing net CO2 emissions?) and is sure does not in the case of vaccine mandates.

I do not see how the Henderson Hooper framework plays out in detail. Would a vaccine mandate be forbidden in every circumstance? Could anti-spread regulation (ventilation, spacing, capacity limits) never apply? For me the answers are yes, sometimes and cost benefit analysis is the way to discuss when.

Comments are closed.