Any defendable normative political philosophy—at any rate, any classical-liberal one—holds that policemen are the citizens’ servants, not their masters. A policeman owes respect to a peaceful citizen and, to a certain point, even to a violent one. The policeman is paid by the citizen, not the other way around. While protecting some citizens, policemen have no right to attack innocent bystanders or protesters.

I use the European term “policeman” (which of course includes policewomen) instead of the American “police officer” for a purpose. It seems to better avoid the implication of extraordinary power and emphasizes that policemen are civilians among other civilians.

Trying to explain police violence in America (which is only endemic in parts of the country), The Economist (“Order above the Law: How to fix American Policing,” June 4, 2010) mentions that “American police patrol a heavily armed country,” referring to private guns, a topic on which the venerable magazine always sees red (not all is rosy in Europe). In this article, don’t miss the photo of a gang of marching police thugs violently pushing down a woman out of their way. And note how rare it is that demonstrators fire guns in America.

Defending a policeman who violently hit a protester on the head with a baton in Philadelphia, the Fraternal Order of Police says its member “only had milliseconds to make a decision” (as paraphrased by the Wall Street Journal: “Viral Videos From Protests Fuel Broader Debate Over Policing,” June 5, 2020). The policeman is now facing aggravated assault and other charges, which is encouraging news.

In the current troubles, many cases of police violence have led to investigations and brought many criminal charges against policemen. As if to put the final nail in the propagandist idea that it is “the rabble” who have been attacked by the police, Ghian Foreman, president of Chicago’s Police Board, the body which receives citizens’ complaints, said he was struck five times by a police baton, even if he was not actually participating in the protest. “I have a perspective now that I didn’t have,” he said (“Thousand of Protesters in D.C., Nationwide Decry Police Abuse,” Wall Street Journal, June 6, 2020).

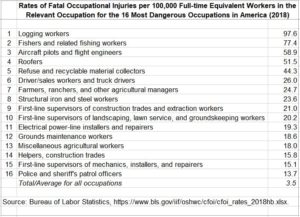

As of June 5, more than 300 policemen had been injured in the current demonstrations and mob looting. Being a policeman is clearly not a job without risk.

However, it is far from being the riskiest job in America, as shown by data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics excerpted on the chart below. Of the few hundred occupations surveyed by the BLS (or at least the ones selected in their summary table online), 15 are more at risk of lethal injuries than a policeman’s job. The risk is 13.7 per 100,000 policemen, which is for times higher than the risk for all occupations, which stands at 3.5. But, to take a few examples, the proportion is 97.6 for loggers, 77.4 for fishers and fishing workers, 18.0 for miscellaneous agricultural workers, and 15.8 for construction helpers.

Moreover, nobody is forced to earn his living as a policeman. If it is important that the ones hired be courageous men and women, it is even more important that they know they are the servants, not the masters, if that’s the only element of political philosophy they have. Let’s hope that the current troubles will help promote this idea. As I have argued before on EconLog, there is a dire need for humble government, starting at the highest level.

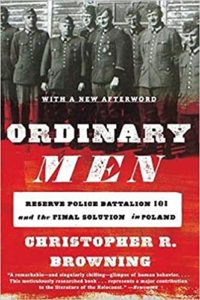

Among the compulsory readings of police trainees, I might recommend Christopher Browning’s Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland (HarperCollins, 1992). Browning explains why middle-aged German police conscripts murdered, usually with a bullet at the back of the head, tens of thousands of Jewish men, women, and children. The reason: esprit de corps, not to look like pussies to their comrades. As you will discover in the book, they were not really forced to participate in these execution squads.

READER COMMENTS

Michael Stack

Jun 7 2020 at 1:52pm

The fact that otherwise-normal people will commit atrocities against others because they can, or to fit in, is really scary.

Pierre Lemieux

Jun 8 2020 at 11:10am

@Michael: Yes. The individualist ideal still has progress to make.

Vivian Darkbloom

Jun 7 2020 at 2:09pm

I’ve got no allusions that policemen and women don’t too often use excessive force or exercise bad judgement when on the job. I’m sure that some are also racist. Nor do I doubt the statistics about the rate of occupational injuries among professions as indicated in the above-referenced chart. However, of all the professions listed in that chart, I think the rate of injury and the threat of serious injury is probably more sensitive to location for “police and sheriff’s patrol officers” than any of the other occupations listed. Does the risk of injury to a roofer differ if he is working, for example, in Minneapolis or Mankato? How about a police officer whose beat is in small town USA such as Mankato versus Minneapolis, St Louis, Detroit, Newark, LA, etc? In other words, in places where violence in general is greatest. It strikes me that the highly publicized examples of actual and alleged police brutality have mainly occured in environments and situations in which responding police are at objectively greater risk. Taking statistics from the US as a whole may not be sufficient to explain the behavior of law enforcement in large, inner cities or the risks they face.

Vivian Darkbloom

Jun 7 2020 at 2:11pm

“I’ve got no *illusions*…,” either!

Pierre Lemieux

Jun 8 2020 at 11:21am

@Vivian:

Your write:

As far as I know, we don’t have the data to evaluate this hypothesis. In more dangerous places, cops have more backup. They also have SWAT teams, tanks, and sometimes grenade launchers–which are themselves part of the problem.

By the way, I would hypothesize that many other occupational deaths show regional/demographic variation. The rate of roofers’ death may be much higher in Manhattan, where there are fewer roofs than in New Jersey suburbs. Fishers’ deaths must be more prevalent in Alaska than in Maine (and certainly than in Wyoming).

Matthias Görgens

Jun 9 2020 at 10:52pm

Fishermen’s death per 100k might not be less prevalent in land locked states? They just don’t have nearly as many fishermen.

Psychologically, injury caused by other people is probably seen as a different kind of danger to accidents. Compare eg people happily driving around in cars but being afraid of terrorism.

Well, I’m just glad I live in a more civilized part of the world.

Weir

Jun 7 2020 at 9:48pm

If we imputed motives to roof tiles, wouldn’t that clear it up? Obviously it’s more dangerous to be a roofer than a cop, and roof tiles are wicked and cruel. Here’s the cause and here’s the effect.

If you’re Montaigne then it’s not like that at all. The contingency that a roof tile happens to blow down and kill me is Kierkegaard’s idea of dumb luck, and random and meaningless death. There’s a venerable philosophy of roof tiles falling on heads, but there’s no ideology of roof tile deaths.

That’s the reality. People care more about uncovering motives than we do about numbers alone. We don’t care about realigning incentives or any practical and effective steps to change things.

Specific actions, like reducing the power of police unions? Or taking away a cop’s pension when he’s committed a crime? Instead we’d rather play-act about how we’re standing up to the Klan.

Pierre Lemieux

Jun 8 2020 at 11:08am

@Weir: Abolishing police unions (that is, their nonrecognition by public employers) would, I think, constitute a desirable institutional change. I am not sure I understand your last sentence, though. The ultimate cause of police violence, I believe, lies in incorrect beliefs about the relations between the state and the individual. And it is not only in America that the impact is greatest on minorities, although it is more visible in America due to the legacy of slavery.

Weir

Jun 8 2020 at 8:56pm

I mean that we should focus like a laser-beam on keyhole solutions, and give up all the cosplay.

We need to grow out of these cosmic, hyperbolic, childish fantasies about how we’re doing battle with white supremacy.

Derek Chauvin is white. Alexander Keung is black. Tuo Thao is Asian. So already that’s white-black-Asian supremacy within one precinct of the Minneapolis PD. Is that what we’re fighting? We can never win that war.

And that’s before we’ve diluted and attenuated the responsibility for George Floyd’s death to all cops, or to America, or to capitalism, or to whiteness, or to whatever nebulous apocalyptic conspiracy encompasses an Abraham Lincoln statue and a statue to black soldiers in Boston Common and any random war memorial in London.

The death toll from our mostly peaceful protests is a disproportionately black one. But the logic of identity politics makes fine distinctions between these victims and those victims. That’s ideology substituting for thought.

Matthias Görgens

Jun 9 2020 at 11:05pm

Keyhole solutions are a great idea!

Especially since they are _not_ exciting. (Though that also make it harder for people to get behind them.)

No clue whether the two keyhole solutions you mentioned would be the right one. That depends on empirical details. But the general idea is a good one!

Randy Burgess

Jun 8 2020 at 4:52pm

I don’t doubt that it is more dangerous to be a cop in a big city like NYC, Chicago, or LA, to name a few, but it’s not like rural cops never get mugged or shot at. I only know from reading and watching videos of shootouts, but anecdotally it does not appear that lots of shootouts are in the cities. Some are, some aren’t. I’m sure the FBI has reliable statistics on this as they do on all crime which would be better than relying on the BLS numbers for cops. There was a famous shootout in Miami involving the FBI and one in LA where the 2 guys had body armor and shot it out with the police for over 2 hours before they were finally taken out. Lots of cops died or were maimed in these shootouts.

I would posit that most shootouts don’t happen in big cities else we would hear about it from the press fairly often. That is the most deadly type of encounter cops face. The stats referenced could be improved, but I’ll bet they’re still pretty close no matter the population density. It’s a lot easier to get away with shooting someone out in the middle of nowhere than it is with people all around.

Matthias Görgens

Jun 9 2020 at 10:57pm

Why do they even have shootouts? Wouldn’t a ‘siege’ work well most of the time? (Even if the suspect shoots, you don’t need to shoot back. Just defend and wait them out until they fall asleep or run out of food and water?)

Similarly for why they seem to still have police chases? Wouldn’t you just call ahead and have some other coworkers set up a street barrier down the road? (Or is the country too big for that?)

BW

Jun 10 2020 at 1:19am

The road networks in cities are probably too dense (too many ways to get from on place to another) for you to not chase criminals who speed away. If you don’t chase them, then they could get off the freeway, drive to a random spot and get out of the car; or just take an unpredictable route to their destination (which you probably don’t know).

At the risk of armchair quarterbacking, shootouts with heavily armed criminals don’t actually happen often enough for there to be an established playbook for how to handle it. If you get a report that criminals are shooting at the police, the cops might assume that they need to chase the criminals for reasons described above. It takes time for the cops to realize the criminals are wearing body-armor, disperse that information among themselves, and formulate a plan. Even then, siege might not be appealing politically because the criminals might escape somehow after killing lots of cops, making the police department look incompetent, or they kill lots of civilians in the area you seal them into, making the police look incompetent or callous.

Ross

Jun 10 2020 at 11:01pm

I believe when I looked up details a few years back it was the case a significant fraction of police deaths were in car crashes, not always on the job, not always (even if on the job) “in pursuit,” but because some police apparently enjoy driving at high speed.

ricky

Jun 11 2020 at 3:03pm

Officers are under tremendous stress. The amount of violence being committed, coupled with pop cultures role in vilifying the police (e.g., “f— the police” culture), alongside how they are portrayed in movies (e.g., “fat person eating a donut”) creates extraordinary animosity.

However, if you look at the data there is clearly NOT systematic racism. Glenn Loury and John McWhorter have already shown this. Video below.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V8fndiNZimA&feature=youtu.be

Warren Platts

Jun 12 2020 at 10:20am

I am not convinced there is a crisis. Yes, apparently, there is a 1 in 1000 lifetime chance of being killed by cops if you are a black man–that is 2.5X more likely than white men. However, this rate has declined dramatically since the 1970s.

On the other hand, you are 12X more likely to by non-police homicide. If you are a black person, you are ~5X more likely to be murdered than a white person; if you are are a black man, you are nearly 6X more likely to be a murderer than a white man is.

Yes, I get it: the police ought to be able to take a 6’6″ 250 lb professional bouncer who is resisting arrest while high on meth and fentanyl and sick with coronavirus while out on parole for home invasion armed robbery with a deadly weapon without killing the guy.

But to extrapolate that into a nationwide or worldwide crisis that must be solved by defunding the police is unwarranted. Recent events have shown that we need more policing, not less, imho. The police in Seattle were told to stand down. The city has not turned into a Libertarian paradise. In the “CHAZ” autonomous zone a self-styled “warlord” now runs the show. Apparently, when there is no police presence, organized crime fills the void. Choose your poison wisely.

Mark O

Jun 14 2020 at 1:31pm

Hi Warren,

I appreciate that your definition of ‘crisis’ is solely in terms of death rates, however I feel that this allows us off the hook a little too easily.

The crisis for black people in America is not just that they might be killed by the police, but that as anonymous citizens they are treated every day as ‘less’ by everyone. The police, in their role as the dispensers of legitimised violence, are simply demonstrating the same values on race that are experienced by non whites in shops, schools, hospitals and …everywhere.

As an English white man who travels extensively in the company of black people, who are often senior to me, I have become aware of how they are treated, compared to me, in normal situations by normal people. I can also assure you this is not an issue isolated to the USA.

What seems to be unique to the USA is this fundamental lack of decency has combined with the understandable fear a heavily armed civilian population and the even more heavily armed criminal population engenders in the people policing it. Fear and respect might make one cautious; approaching a rattle snake. Fear and disrespect is a poisonous cocktail when it has been consumed by a person holding not only a gun, but all the cards too.

Craig

Jul 23 2020 at 1:39pm

I remember NYC in the late 70s into the 80s. The Bronx was burning, crime was out of control, everywhere basically. Movie genres depicting an even more lawless future such as Escape from NY, Mad Max (the original), Robocop, etc. And then — ‘broken windows’

This is why I am mostly behind the thin blue line. I can remain there and not support Chauvin.

The crime statistics are quite clear that there is a major inflection point at approximately 1990. From that point on, violent crime in the US has dropped significantly.

With respect to the more recent protests/riots. The problem is that when protests turn into riots, the police can no longer individualize policing. If there is a spectrum between policing a community at peace and the laws of armed conflict, these riot situations are somewhere in between. And of course something very expected will happen. A peaceful protestor will be attacked by the police at a riot.

Right now what I am seeing is absolutely unconscionable. I’ve seen what these riots do to cities. Originally from NJ, to this day Newark, NJ has never really recovered from the riots.

Difficult times, right now I would suggest the US is teetering.

Comments are closed.