“Science fiction is not predictive; it is descriptive.”

Ursula K. Le Guin

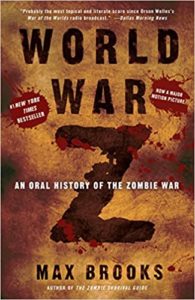

World War Z is not a new book. But it’s a book worth reading (or revisiting) when thinking about emergency powers and public policy. Don’t worry if you’re not a fan of the zombie genre—this book reads more like a Ken Burns documentary than an episode of The Walking Dead.

Ursula K. Le Guin described science fiction as a thought experiment, and that’s how Max Brooks approaches his story: Let’s say the world was struck by a zombie pandemic.

The reader interested in questions about economics and public policy in a free society will find herself considering a world without easy answers. The pandemic imagined in World War Z is devastating. It begins with an interview in Chongqing, an area that “at its prewar height…boasted a population of over thirty-five million people. Now, there are barely fifty thousand.” Humanity has survived—barely—not merely a pandemic, but near extinction.

In the unlikely event that any reader in 2020 fancies themselves without preconceptions about the right response to a global public health threat, Brooks pushes these convictions to their limits. Expert failure and government failure, but also the limits of liberalism and the great society are all on full display. There’s no unicorn governance in this zombie apocalypse.

Eerily, it all begins with an outbreak in China, a cover-up, and unheeded warnings.

Brooks speculates about plausible failures (maybe even the inability) of modern, liberal- democratic governments to prepare for an apocalypse scenario. Once concerns can no longer be dismissed outright, many politicians institute cheap, showy, early-stage responses but balk at the expensive and unpopular elements of a thorough response. The military undergoes costly trial and error as it comes to grips with how ill- suited tactics developed for fighting the living are for fighting the undead. Skeptics of big government may nod along. Those who see value in grand plans will be frustrated.

But there’s just as much in the book to prompt the opposite reaction. Invasive, expensive, expert-guided government is successful for some. Peace, opulence, and specialization leave citizens as unprepared as their governments. Successful nations in the book benefit from physical borders—walls, mountains, and oceans—and military might. The entire economy is subsumed to plans to survive the war and human wishes, property, and even lives are reduced to deployable and often expendable resources. And many survivors of the Zombie War find satisfaction in manual labour (baking bread?) and community as members of a truly shared endeavour.

Hayek wrote that the government’s regard for limiting its action to what’s required to sustain the liberal order may be “temporarily suspended when the long-run preservation of that order is itself threatened. But a decade after the end of the book’s hostilities, loss of life has collapsed the extent of the market. Division of labour has broken down. Governments retain incredible levels of control. Survivors think of those who have too much regard for individual plans and wishes as selfish. In some places, the liberal order was lost anyway—a reminder that having a good reason to do something doesn’t mean that doing something will give us the outcome we want.

The virtue of this book lies in the discomfort it should cause when readers challenge their political convictions. Less comfortable still is the book’s apparent prescience in light of the 2020 pandemic—drastic change turned out not to require a zombie apocalypse. It’s a more useful thought experiment than we’d like.

Janet Bufton (Neilson) co-founded the Institute for Liberal Studies in 2006 and has worked as a program coordinator with the Institute for Liberal Studies since 2013. She manages the Liberal Studies Guides project.

READER COMMENTS

IronSig

May 12 2020 at 11:42pm

Recollections from book have been stirred up in my mind frequently since February.

The viral origin from grand Yangtze dam projects and spread by black market organ transplants;

The black comedy failure of the showiest shock-and-awe to dent the press of the undead;

The nuclear winter instigated, not by Pakistan and long-term hostile neighbor India, but Pakistan and their sudden fury at Iran;

The indulgent celebrity compound that’s overrun aftertheir tone-deaf live streams and the unnamed Ann Coulter and Bill Maher are slaughtered;

The evaporation of Israeli-Palestinian conflict when Israel takes the threat as a Black Swan risk, cedes the West Bank when they retrench, and invite anyone willing to pass the dogs to enter the country;

Chief of all, I worry that too many of our political lever-pullers and business leaders today will declare a victor from the Methodenstreit. I was a teenager at the time, but when I read the former Economic Advisor’s chastisement of the interviewer for romanticizing the freedom and specialization of the market society, I was chilled. I could see my own rationalist tendencies in an anti-hero, and a technocratic one at that.

I was not at all surprised to later hear from Arnold Kling when he was promoting

“Specialization and Trade” how the mechanical and statistical optimization techniques pioneered during World War 2 were joined with the intense rationing to maximize the war machine, and how the same techniques have a tendency to crowd out the imagination necessary for innovation and entrepreneurship.

Matthias Goergens

May 13 2020 at 12:52am

I enjoyed reading the book. But the zombie apocalypse as described only worked because every single person in charge (and the rest of the population) was holding the idiot ball.

I wonder, if you could construct a zombie apocalypse that worked as a scenario, even if there were a few smart people around?

Adam

May 28 2020 at 12:17am

Certainly, all you need is “fast” enough zombies.

Comments are closed.