Robin Hanson has a very interesting blog post discussing the fact that authorities do not update their forecasts as frequently as an optimal forecaster would:

The best estimates of a maximally accurate source would be very frequently updated and follow a random walk, which implies a large amount of backtracking. And authoritative sources like WHO are often said to be our most accurate sources. Even so, such sources do not tend to act this way. They instead update their estimates rarely, and are especially reluctant to issue estimates that seem to backtrack.

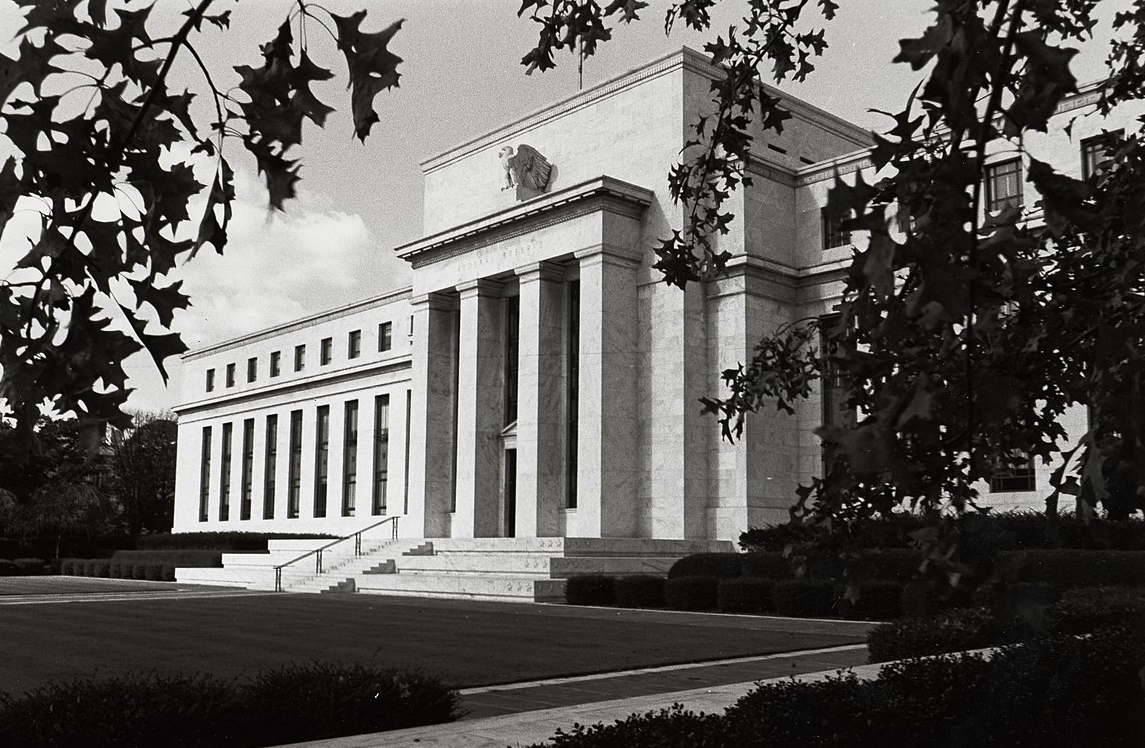

The random walk observation reminded me of a column I wrote for The Hill back in 2018, criticizing the way the Fed conducts monetary policy:

In December 2015, the Fed raised its interest rate target for the first time in more than a decade. At the time, Fed officials signaled another four rate increases for 2016 in order to prevent the economy from overheating. Unfortunately, the economy quickly slowed, and the Fed would not raise rates again until the following December. Indeed by early 2016, it was clear that the previous rate increase should not have occurred.

So why didn’t officials immediately admit their mistake and cut rates back to zero in early 2016? It turns out that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) has been exceedingly reluctant to quickly reverse course after setting out on a new policy track.

This is very different from how asset markets work. If stocks fall on Tuesday due to worries about a trade war, the market is not at all reluctant to shoot right back up again on Wednesday, if new information makes that scenario less likely. Unlike Fed policymakers, markets don’t have egos and they don’t worry about “credibility.”

Then I suggested a reform to make Fed policy more accurate:

Given modern technology, there is no reason why the Fed can’t adjust its settings far more frequently. FOMC members could, for example, email their preferred interest rate target to Chairman Powell each business day, and the actual Fed target could be set at the median vote.

Instead of quarter-point increments, FOMC members could select an interest rate target to the nearest “basis point”—which is 1/100th of 1 percent. Daily movements would look more like a financial asset price, moving up and down each day in a sort of “random walk” as new information about the economy comes in.

Toward the end of the article, I cited an example of what can go wrong when Fed officials are reluctant to shift course:

Consider the following quotation from the minutes of a November 1937 Fed meeting. In this meeting, Fed officials considered reversing their earlier decision to raise reserve requirements — a decision now blamed for helping to trigger a severe double-dip depression in late 1937, throwing millions out of work:

We all know how it developed. There was a feeling last spring that things were going pretty fast… If action is taken now it will be rationalized that, in the event of recovery, the action was what was needed and the System [Fed] was the cause of the downturn. It makes a bad record and confused thinking. … I would rather not muddy the record with action that might be misinterpreted.

Here we see a Fed official arguing that a reversal of the previous mistake would be taken as evidence of Fed guilt — especially if it was successful!

READER COMMENTS

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Apr 15 2022 at 7:37am

Unlike Fed policymakers, markets don’t have egos and they don’t worry about “credibility.”The “ego” part I understand and think is correct. Not the “credibility.” Failure to quickly correct announced tactics — explaining how the new information or an improved model justifies the change — reduces the Fed’s credibility.

Jose Pablo

Apr 15 2022 at 11:17am

No, it does not reduce it.

FED officials’ credibility is like Pope’s credibility: it is based on other people believing in their infallibility. They are picked up to be infallible. They show they are not; you lost the credibility of your infallibility. Why you were wrong is, at best, a second thought most people don’t even care about.

And, in any case, the explanation would be, very likely, too technical for every single politician and 80-90% of market participants. Infallibility on the other hand (or the lack thereof) … that everybody can see and understand (even the politicians!).

Scott Sumner

Apr 15 2022 at 1:20pm

That’s why I used scare quotes for “credibility”. Not hitting their goals actually reduces credibility.

Spencer Bradley Hall

Apr 15 2022 at 9:09am

The 2 yearlong deceleration in required reserves (which are driven by payments), ended at the same time the FED raised its interest rate target. I.e., monetary policy had already been progressively tightening.

Prices troughed in Jan 2016 as long-term money flows fell by 80 percent from 1/2013 to 1/2016. Oil fell by 70 percent during the same period.

The mistake caused China to devalue their currency 3 times in August 2015, or by c. 4%.

Jose Pablo

Apr 15 2022 at 11:09am

It is not an “ego” problem. It is an “incentives” problem. I tend to thinkg that market participants (particularly big ones) are more prone to outsized egos than FED officials. In an “ego fight” between Jamie Dimon and Jerome Powell I will bet on Jamie, this is a no brainer.

Market participants have a P&L. They either trade with their own money or make money depending on how sucessful their trading is.

FED officials on the other hand …

marcus nunes

Apr 15 2022 at 6:34pm

Another example of “Fed Guilt”: Tim Geithner in 2008:

“The argument that makes me most uncomfortable here around the table today is the suggestion several of you have made—I’m not sure you meant it this way—which is that the actions by this Committee contributed to the erosion of confidence—a deeply unfair suggestion.

… But please be very careful, certainly outside this room, about adding to the perception that the actions by this body were a substantial contributor to the erosion in confidence.”

Scott Sumner

Apr 16 2022 at 2:31pm

Yes, that’s just a disgraceful statement by Geithner. Utterly disgraceful.

Matthias

Apr 17 2022 at 8:58pm

I like that your article basically prepares a slippery slope for the Fed to be replaced by asset or prediction markets.

More freebanking would also be a step in the right direction, since then private money creation could do more of the short term adjustments.

(Politically, I don’t think we are getting privately issued notes again anytime soon, but technological changes are making bank notes less important these days.

I would welcome a world where people regularly used Amazon balances to settle trades, backed by the full might of Amazon’s balance sheet (and might operation), and not some cash reserves.)

Comments are closed.