A commenter named Ted once asked me a series of interesting questions, and I’ve since done a few “Ted talks” over at MoneyIllusion. Today I’ll do one here, in response to this request:

More posts on how public opinion isn’t real (for me, this was a big takeaway from your writing)

I’ve already done a few posts on this, but I don’t believe I’ve put all my reservations into one place. Here are a few:

1. Political correctness

2. Framing effects

3. Innumeracy

4. Budget constraints

5. Fragility

I’ll take them in order, starting with two obvious points (for completeness):

1. People like to look good. They are prone to answer questions from pollsters in ways that make them look good. There’s the famous “Bradley effect” where California voters were reluctant to tell pollsters that they did not intend to vote for the African-American candidate. I wonder if that wasn’t also a part of Trump’s surprise win?

2. Poll results depend on the way a question is worded. Consider a poll question that asked, “If you found out that a candidate was pro-abortion, would you be more likely to vote for them?” How about if the wording were changed from anti-abortion to pro-choice? Which question will get more “yes” responses? Admittedly, those aren’t exactly the same poll question, but my point is that survey questions are often worded in loaded ways, and that this affects the results.

I believe the next three are bit less obvious:

3. I recall an interesting set of polls back around 1990. People were asked what rate of increase in Medicare spending was appropriate, starting with 0% to 2%, then 2% to 4%, all the way up to 10% or more. Only about 2% of respondents favored more than a 10% increase. At the time, President Bush was getting a lot of negative press for his Medicare “cuts.” I don’t recall the exact numbers, but I seem to recall that Bush proposed “cutting” the increase from roughly 11% to 9%. In another poll, people were asked if they favored Bush’s Medicare cuts, and about 2/3 disapproved. And yet only about 2% actually favored spending more than Bush, when confronted with actual numbers. Do you see the problem? The same problem applies to polls regarding higher taxes on the rich, versus questions about the appropriate top tax rate. People might say they favor higher taxes on the rich, but then advocate a 30% top rate (lower than today), when asked.

Suppose you had three public opinion polls. The first asks whether military spending should be above or below $700 million. The second asks whether it should be above or below $700 billion, while the third asks if it should be above or below $700 trillion. My hunch is that the results of all three polls would be quite similar. I doubt that most people have even a clue as to the current level of military spending (close to $700 billion.) Readers of this blog probably know, but you are above average in knowledge of public affairs.

So what do people “really believe”? There is no “really believe”. It’s a nearly meaningless concept. The only thing real is the lever they pull in the voting booth.

4. Democratic pundits often like to point to polls showing that “the public agrees with them”. Thus if you ask people if they want all sorts of free goodies like health care, day care, free college education, great infrastructure, etc., they tend to say yes. Dems often fail to mention that the public is less enthusiastic about the sorts of tax increases that would be required to pay for euro-style benefit programs. Recall the recent riots in France, partly motivated by a higher gas tax.

To be meaningful, you’d have to sit Topeka voters down in a room with the Kansas state budget and tax revenues shown in a pie chart, tell them that the state constitution requires a balanced budget, and then ask them how much taxes they want to pay and where it should be spent. That’s what politicians actually do, but that’s not a question asked by pollsters.

5. Rather than being a stable parameter, public opinion is very fragile. Polls might show that most people believe X, but as soon as the issue rises to prominence and more information comes out, their views might shift radically. I often talk to people about the importance of allowing a market for kidneys. The first reaction is often negative, as people wonder if this approach would be biased against the poor. Some even fear the theft of kidneys from unwilling donors. It only takes me two minutes to convince them otherwise. The theft of kidneys occurs when there is a black market created by shortages. A market would actually help the poor because it would be cheaper for the US government to pay for kidney transplants for the poor than to continue supporting those with kidney disease under Medicaid. We’d save lives and money. Once you simply point out the facts, public opinion shifts quickly.

Now imagine that this currently obscure issue suddenly became a big deal, and all these questions were being publicly discussed. It’s easy to see that “public opinion” might be easily shifted away from the current position, which is based on very little knowledge.

You might argue that this example doesn’t show that public opinion doesn’t exist, just that it’s easily shifted. But it’s even worse. I’ve previously compared public opinion to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Just asking the question can affect the results. Consider “Do you favor paying kidney donors?” Now consider, “Do you favor paying kidney donors in a regulated program that would provide free kidneys for all poor people in need, reduce total government health care spending, save many thousands of American lives each year, all while eliminating the ugly black market in kidneys stolen from poor people?” Hmm, which question gets more support? Just asking the second question tends to educate voters on the policy, and hence shift public opinion.

Here’s another interesting question to ask:

“Suppose a worker is a bit slow, perhaps low IQ, and can only produce about $12 worth of output per hour. He is working in a small family run Iowa business making Christmas ornaments. Do you favor Congress passing a law that would effectively make it illegal for that worker to negotiate a wage where he would be able to keep his job?”

How about this question?

“Do you favor a $15/hour minimum wage?”

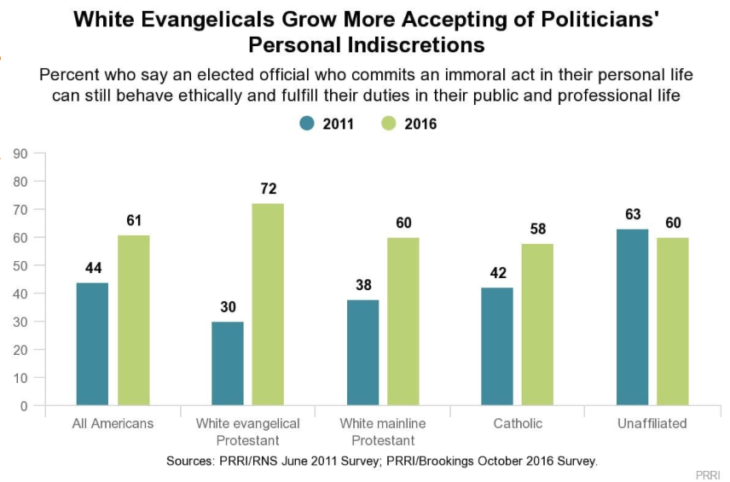

After I wrote this post, I came across a post by Scott Alexander that reminded me of another problem. It seems that President Trump is such a polarizing figure that he is literally shifting “public opinion” on a host of issues. Thus support for trade and immigration is rising, especially among Democrats, perhaps as a backlash to Trump. In another poll, white evangelicals recently had a massive shift in opinion on morality. Just seven years ago (when Bill Clinton was fresh in everyone’s mind) white evangelical voters thought moral behavior by public officials was very important. In 2016, (with Trump on everyone’s mind) opinion shifted dramatically in the opposite direction. So what do white evangelicals “actually believe” about morality? That’s not even a question, as it presupposes public opinion existing in the same sense that Mt. Rushmore exists.

In my view, none of these surveys of liberal Democrats or conservative evangelicals are reliable guides to public opinion. Much of what’s going on is actually a sort of “boo Trump” or “yeah Trump”, disguised as actual, principled views on various issues.

READER COMMENTS

Lorenzo from Oz

Dec 18 2018 at 5:13pm

What you said.

Framing effects are very powerful. Reuters-Ipsos did a poll in Jan-Feb 2017 which found that 58% of Brits identified as feminist.

In late 2015, the Fawcett Society, a feminist advocacy group, had a poll conducted that found that 9% of British women and 4% of British men identified as feminist.

Lorenzo from Oz

Dec 18 2018 at 5:17pm

What you said.

Framing effects are very powerful. In Jan-Feb 2017, Reuters Ipsos conducted a poll that found that 58% of Brits identified as feminist.

In late 2015, the Fawcett Society, a feminist advocacy group, had a poll conducted that found that 9% of British women and 4% of British men identified as feminist.

The Reuters poll framed things so as to maximise ticking feminist. The poll for the Fawcett Society was much more professional.

(I would add links, but then it gets dropped into the spam/moderated bin.)

Mark Z

Dec 18 2018 at 6:04pm

Another problem – and reason why markets are in a sense more ‘democratic’ than democracy is that opinion polling, even if perfectly accurate, does not really measure intensity. If you ask the public if they support of oppose policy A, and 60% support it while 40% oppose it, but the 60% who support it really only favor it slightly over its absence and are virtually indifferent on the matter, while the 40% who oppose it consider it a life-and-death situation, what then does public opinion say about policy A? Even a majority of 90% isn’t very meaningful if almost all of them are pretty close to indifferent about the question and just lean ever so slightly to one side.

It would be more meaningful to ask people, ‘how much would you pay to make your preferred outcome happen? /how much would you have to be paid to let the other outcome happen?’

Scott Sumner

Dec 19 2018 at 12:10pm

Lorenzo and Mark, Good points.

E. Harding

Dec 19 2018 at 9:24pm

Correct, Sumner. “Public opinion” depends entirely on the question being asked (e.g., the supposed 96% support for expanded background checks that seems to be around 50% lower in actual election results). However, election results definitely exist. And they do tell us interesting things about how effectual opinion differs between people. Take a look at this, for instance:

https://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?fips=37&year=2018&f=0&off=51&elect=0

https://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?fips=37&year=2018&f=0&off=52&elect=0

https://uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/state.php?fips=37&year=2018&f=0&off=53&elect=0

mbka

Dec 20 2018 at 1:07am

One more issue: voters are usually asked to either vote for a whole package of measures, consisting of many elements (example, political parties or presidents as the only choice), or they are asked for single measures in isolation without any consideration of trade-offs (referendums). Both measures give a completely misleading picture, even if you use the “average” opinion, and even if you assume perfect information about the issues.

In the package case, the Arrow theorem and assorted research have shown that it is impossible to aggregate preferences, even in theory. Different people will rank their preferences differently, and packages always tend to contain elements we actually dislike. e.g. “The voter” “wanted” “Trump” is a sentence with three components, all three of which are multifaceted – the entire sentence is meaningless as a result.

In the single issue case, people are asked to vote for or against issues without any embedding into concomitant trade-offs. Example, “The British” “wanted” “Brexit”. Even without unpacking “The British” and “Brexit” into their constituent parts, the biggest flaw here is the absence in the question of possible different kinds of trade offs associated with Brexit, or any other hint of “under which conditions”.

So, while a democratic vote provides a defensible technique for decision-making, it should not be taken as a literal truth or expression of anyone’s actual opinion – even in the ideal case of well-informed electorates.

Benjamin Cole

Dec 20 2018 at 8:05pm

Donald Trump wants to pull US troops out of Syria. And next, Afghanistan.

Because it is Donald Trump, these are treated as bad ideas.

And that is not even Public Opinion—that is the Washington establishment .

gjk

Dec 20 2018 at 10:45pm

One additional problem is excessive “interpretation” by pollsters. Once, I saw a poll that said that something like 80% of Americans don’t “believe in” evolution.

I decided to dig deeper, found the poll questions, and it turned out that the poll question was something like “do you believed that life originated by the actions of a supreme being? yes or no.” Apparently, you only “believed in evolution” if you answered “no” to the question.

It should be obvious that there are numerous ways that a belief in a supreme being reconciles with the mechanisms of evolution, and don’t necessarily require “intelligent design”. So, the poll “interpretation” was headline-grabbing garbage.

I wonder how many other polls have this level of “overcooking” in the interpretation?

Comments are closed.