During the latter part of the 20th century and the early 21st century, a consensus emerged that industrial polices were counterproductive. This view was a part of what was known as the “Washington Consensus”.

Unfortunately, economics goes through cycles as one fad after another becomes fashionable, at least until society painfully relearns the fundamental principles of economics. In recent years, industrial policy has come back into style in the US and indeed much of the world. But the new industrial policy doesn’t work any better than previous iterations. Here’s Bloomberg:

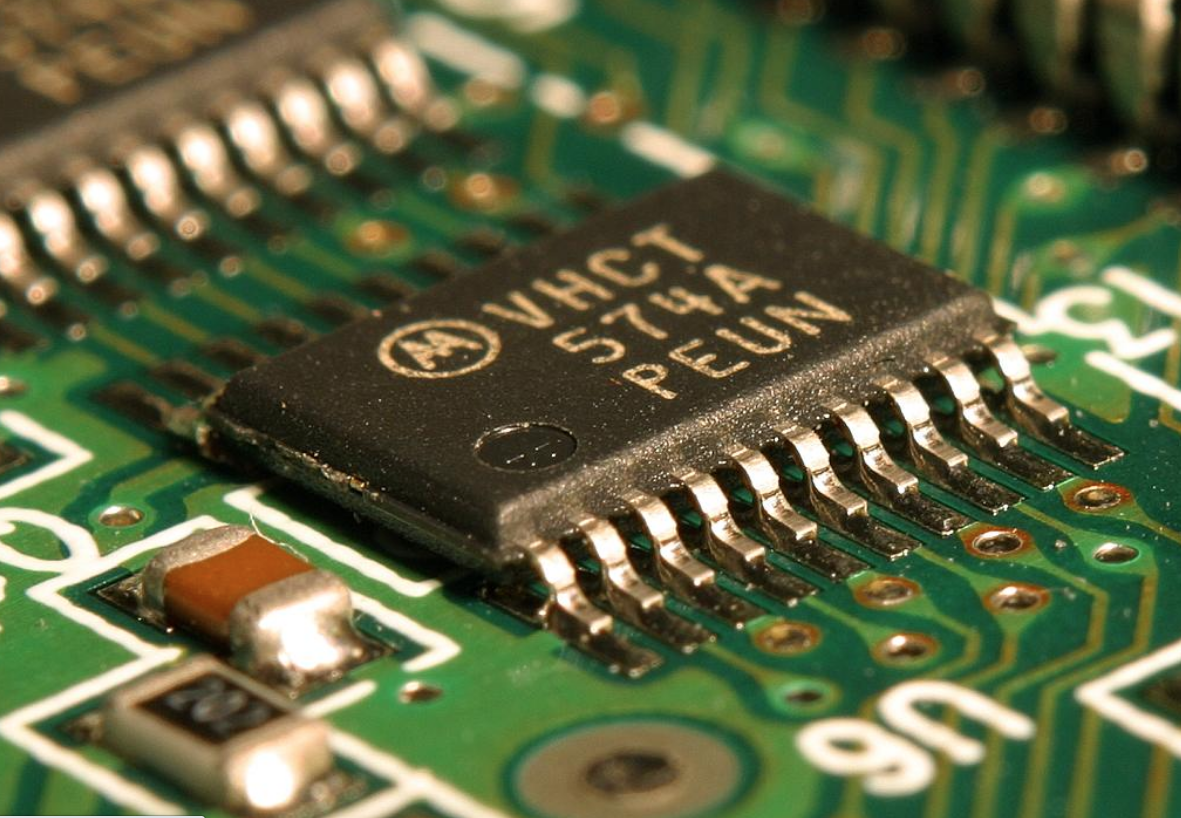

By now it’s clear that the Chips and Science Act — which includes a $52 billion splurge for the semiconductor industry — is unlikely to work as intended. In fact, its looming failure is a microcosm of all that’s wrong with America’s current approach to building things.

Bloomberg cites several factors, including regulations that lead to very long delays in constructing new plants. And even bigger problem is our immigration system:

Another challenge is that the US lacks the needed workforce for this industry, thanks partly to a broken immigration system. One study found that 300,000 more skilled laborers may be needed just to complete US fab projects underway, let alone new ones. Yet the number of US students pursuing advanced degrees in the field has been stagnant for 30 years. Plenty of international students are enrolled in relevant programs at US schools, but current policy makes it needlessly difficult for them to stay and work. The strains are showing: New plants planned by Intel Corp. and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. are both struggling to find qualified workers.

Even worse, chipmakers are burdened with regulations aimed at helping labor unions:

Companies hoping for significant Chips Act funding must comply with an array of new government rules and pointed suggestions, meant to advantage labor unions, favored demographics, “empowered community partners” and the like. They should also be prepared to offer “community investment,” employee “wraparound services,” access to “affordable, accessible, reliable and high-quality child care,” and much else.

Over in Foreign Policy, Adam Posen has a more in-depth examination of the problems with industrial policies:

This policy approach, while having considerable popular appeal at home, is based on four profound analytic fallacies: that self-dealing is smart; that self-sufficiency is attainable; that more subsidies are better; and that local production is what matters. Each of these assumptions is contradicted by more than two centuries of well-researched history of foreign economic policies and their effects. Neither the real but exaggerated threat from China nor the seeming differences of today’s technology from past innovations change underlying realities.

Posen discusses many specific problems with industrial policies, but most of them boil down to one specific error—ignoring opportunity costs.

READER COMMENTS

Brett

Mar 28 2023 at 4:19pm

It’s going to pivot into more of a “friendshoring” set-up over time, with places ranging from Canada to Vietnam getting some broad exemptions on the rules from it. We’re already seeing some of that in recent deals with the Biden Administration.

That could be very useful in its own way. Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea all benefited enormously from the US allowing them to export openly to its market in the Cold War, because it was politically useful to bolster the economies of our allies. Maybe the “friendshoring” recipients in poorer countries will get that perk as well.

Scott Sumner

Mar 28 2023 at 5:35pm

Vietnam is a “communist” dictatorship. The fact that they are viewed as “friends” speaks volumes about our foreign policy.

vince

Mar 28 2023 at 5:31pm

We absolutely need industrial policy. As the blog indicates, the policy should start with reform of our educational system.

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2023 at 12:32pm

Education is one of (if not the most) the most highly planned industries in the country. The reform movement most gaining traction now (on both the Right and the Left) is school choice, seeking to break the monopoly of industrial planning.

vince

Mar 29 2023 at 12:35pm

Higher education needs reform too.

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2023 at 12:46pm

Agreed and for the same reason I listed above.

The solution is not more industrial planning, but less.

Jose Pablo

Apr 2 2023 at 6:29pm

Education, particularly the higher one, is socially useless

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Case_Against_Education

Mactoul

Mar 29 2023 at 3:04am

Didn’t China itself grew via large-scale industrial policies that led to largest poverty alleviation ever.

Other Asian countries too pursued industrial policies and have been economically successful.

Perhaps America is too dysfunctional to make a go of industrial policy rather than industrial policy being counter-productive per se.

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2023 at 5:01am

No. It was the abandonment of industrial policy and the liberalization of their economy in the 70s that led to their growth and poverty alleviation. Since abandoning that trend in recent years, China has been backsliding.

Same with other Asian countries. They’ve grown despite industrial planning and not because of it.

But even if one wants to point to Asia as a success story, one has to answer why the exact same sort of industrial planning has failed in Africa, Central and South America, Europe, and the US.

Mactoul

Mar 29 2023 at 11:23pm

Maybe Asians are better at industrial policy– higher IQ, more social cohesion etc.

Jon Murphy

Mar 30 2023 at 6:55am

No, that’s unlikely. For one, we need an explanation that doesn’t rely on “just so” stories. For another, we need an explanation why IQ and social cohesion matter for industrial policies. For a third, we need an explanation why those policies cannot be transplanted.

And all that is assuming that industrial policies worked in Asia. The evidence says they didn’t.

sk

Mar 31 2023 at 10:19am

Not totally true. A developing economy moving off a low base can institute a degree of industrial policy with some success. China only opened to a degree. Now that it has achieved size, it will be questionable if it can be successful with an industrial policy. Industrial Policy is not very successful in mature economies for any number of reasons that you are surely aware of.

Jon Murphy

Mar 31 2023 at 1:21pm

Right, but it’s their opening that caused the growth, not the industrial policy.

Scott Sumner

Mar 29 2023 at 11:52am

Jon is exactly right. I would add that not only did China do much better as it has reduced its focus on industrial policy (after 1978), it’s also the case that a cross sectional examination of East Asian countries shows that GDP/person tends to be higher in the more free market regimes.

Jim Glass

Mar 29 2023 at 5:15pm

not only did China do much better as it has reduced its focus on industrial policy (after 1978),

I dunno, but ISTM that categorizing Mao’s Cultural Revolution as “industrial policy” is perhaps a bit harsh.

Scott Sumner

Mar 29 2023 at 5:50pm

Not the Cultural Revolution itself, but certainly the economic system in place at the time (and immediately before and after the CR.

Michael Sandifer

Mar 30 2023 at 11:29pm

Yes, and if China had less of a heavy hand since the late 70s, its economy would have grown even faster. In fact, it could have grown much faster. Just look at some of the annual growth rates for South Korea, for example, while it was a developing country.

Jim Glass

Mar 29 2023 at 5:05pm

Didn’t China itself grew via large-scale industrial policies that led to largest poverty alleviation ever.

Not even close.

The Communists’ planning arm (such as it was) was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution. The peasants decided they didn’t want to starve any more and started organizing markets, farms and rural industries for themselves. The Party tried to stop them but couldn’t, then saw the profits coming in and decided to go along for the ride, co-opting them (when not confiscating them) for itself.

How the Farmers Changed China: Power of the People

The Secret Document That Transformed China

Mark Bahner

Mar 31 2023 at 9:28pm

Wasn’t the “Great Leap Forward” the biggest example of Chinese “industrial policies”?

Knut P. Heen

Mar 29 2023 at 8:32am

I thought industrial policies now were labelled “sustainability policies”.

vince

Mar 29 2023 at 1:58pm

There’s part of the problem–lack of an exact, universal definition. What is and what isn’t industrial policy?

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2023 at 2:04pm

What do you mean? There’s a pretty common understanding of what industrial policy is. Has been the case at least since Adam Smith, who writes about it in Wealth of Nations.

I’m unaware of any debates about whether X or Y is industrial planning. Rather, the debates seem to be more “should Industry X be planned?”

vince

Mar 29 2023 at 5:04pm

An example is the way you refer to industrial policy and then to industrial planning. Are you defining them identically?

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2023 at 5:18pm

No. Typo on my part as I am firing off a quick response to you in between projects. I mean “policy” (although there can be significant overlap).

Jim Glass

Mar 29 2023 at 4:12pm

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI and ChatGPT fame, considers the SVB Bank collapse and says the government should guarantee all bank deposits because depositors must not doubt that their deposits are safe.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uc2YvvyP-Ks

He also gets a bit snarky about the idea that depositors should check the financials of banks they deposit in. “Do we really want them to have to do that? I would argue no.”

But then, he didn’t ask ChatGPT about it.

vince

Mar 30 2023 at 4:36pm

SVB seems off-topic, but since you brought it up and it fits in with government picking winners and losers–whether industrial or monetary policy–the FDIC announced 3/26 that it was selling SVB assets to First Citizens Bank.

Did the FDIC negotiate fairly on behalf of taxpayers? Not according to First Citizens stock price. It was $583 before the announcement and $869 afterward. Meanwhile, the S&P was flat.

vince

Mar 29 2023 at 8:17pm

Why would the complaints about industrial policy not also apply to other government interventions, such as monetary policy, with its bailouts and centrally planned control of the money supply?

Some examples:

1. picking winners and loser

2. the knowledge problem

3. corruption

Jon Murphy

Mar 29 2023 at 9:35pm

They do

Jose Pablo

Apr 1 2023 at 6:45pm

“the real but exaggerated threat from China”

What real threat from China?, to be precise

Comments are closed.