Poverty and Inequality

By Pedro Schwartz

“I used to study poverty, inequality, and growth (or the lack of it) as separate phenomena, often locked in a diabolical trade-off… far from being inimical to one another they are complementary factors in the evolution of human welfare.”

The stagnation of the incomes of the white and blue collar middle class in advanced economies can be explained in part by Third World competition; another part must be due to changes in technology. From the point of view of the welfare of humanity, the news is good. Those who refuse to see how much globalization is doing for the poor may be wearing their anti-capitalism as a fig leaf to cover their short run appetites. World poverty is not increasing nor is inequality widening. The number of the poor, especially among the most destitute, is reducing steeply which, of course, means that world inequality is diminishing. All this is happening within the framework of secular economic growth temporarily suspended by the late economic crisis. The stagnation of the incomes of the white and blue collar middle class in advanced economies can be explained in part by Third World competition; another part must be due to changes in technology. From the point of view of the welfare of humanity, the news is good. Those who refuse to see how much globalization is doing for the poor may be wearing their anti-capitalism as a fig leaf to cover their short run appetites.

The United Nations proclaimed their Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 1990: the first one was “halving the proportion of people with an income level below $1/day between 1990 and 2015”. The goal has been met ahead of schedule (United Nations, 2013) and the consensus in the economics profession now is that indeed world poverty has been on the retreat for more than forty years. One of the first champions of this view was Xavier Sala-i-Martin, of Columbia University and Pompeu Fabra School of Economics in Barcelona. For more than a decade, he has been fighting to make the United Nations and the World Bank admit that poverty was falling much more quickly than expected and the facts have borne him out.

Sala’s latest paper written with Maxim Pinkovskyi (2009) has broken new ground for me from the very start. I used to study poverty, inequality, and growth (or the lack of it) as separate phenomena, often locked in a diabolical trade-off. I now see that their mutually reinforcing effect comes to light when studied together under the conceptual umbrella of the distribution of income: far from being inimical to one another they are complementary factors in the evolution of human welfare.1 So, let me start by paying attention to Sala-i-Martin and Pinkovskyi (P&S).

The evolution of world poverty 1970-2006

With the MDGs, studies of the evolution of world poverty have been coming hard and fast.

They could be classified into two groups: those that use direct surveys of income distribution and those, like P&S, who use per capita national income figures.2 Whatever the source of the data, the profession normally applies a conventional definition of absolute poverty as a per capita income or consumption below $1 or $1.50 or $2 a day.3 From any civilized point of view these levels of income or consumption are pretty basic and unsatisfactory, so that people above the different lines so defined must still be considered very poor. The point of the exercise is another, however: it is to measure how fast, in what numbers, and by what means the poor are emerging from dire destitution.

The dividing lines mentioned above try to measure absolute poverty and whether it is shrinking. Many people in the scientific community and among practical political economists would prefer us to focus on relative poverty.4 In my view, however, relative poverty is a less defensible notion than absolute, since it tries to count the number of people whose consumption is some percentage below the median income, usually 60% of the income of the person exactly in the middle of the population, income-wise. Now this is not so much a definition of poverty as a controversial indicator of inequality: by definition, there will always be people below the median and this relative poverty will only shrink in as far as the population clusters around the center. Also by definition, relative poverty will never disappear, so that there will always be a part of the population claiming the right to have their income supplemented by society, no account taken of their capacity to better their own condition. Who is ‘society’, anyway? Better leave the discussion of the presumed claim of all to become ‘full participants of what society has to offer’ or to aspire to ‘full citizenship’ for another day. Here I will simply note what this has meant in practice in advanced societies: the creation of a dependency culture in a self-perpetuating under-class, a development not attributable to the free market but to policies fostered by the social liberalism of intellectual élites.5 My intent will be narrower and more modest. I will be content with measuring the number of those who have emerged from absolute poverty through economic growth and have thus made the world more equal.

Now, measuring world poverty and equality is a difficult exercise demanding the use of a wide range of statistical methods. Let me concentrate on Pinkovkiy and Sala-i-Martin (2009), who address world poverty figures by calculating GDP per capita in 191 countries during the years 1970 to 2006.6 I will go straight to three of their graphs from their (2009) article, which I reproduce with due permission.

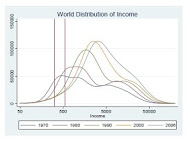

Figure 1 shows how the distribution of income in the world has changed over those thirty-six years. The two red vertical lines show the yearly income of people getting $1 and $2 per capita a day: the latter being $730 a year.7 The blue curve for 1970 encompasses a large number of people under it and to the left of the red vertical lines and therefore in dreadful poverty. It also shows two humps of inequality around $1,000 and $4,000. Add to this that the curve is widely spread, in itself another sign of inequality. The further we move down the years, the fewer the people to the left of the red lines and the higher the concentration around the median: people are getting better off and wide divergences in income are getting compressed.

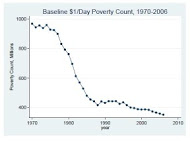

Now, for the head counts. From 1970 to 2006 world population increased by some 2.88 billion, so that the number of poor should have increased even if their personal situation had improved overall. However P&S calculate that the number on $1 a day fell by 617,100 and those on $2 fell by 782,900. Some fall!8 What Figure 2 shows is how many people are left whose income is equal to or less than $1 a day. According to P&S there are 350,400: the fall is precipitous. The numbers for $2/day are 847,000 and on $3/day, 1.39 billion. These are still large numbers and they suggest the

very stark conditions under which so many people live from the point of view of well-being. Still, progress has been unexpected and huge.

For those who are not content with measuring poverty with per capita income or consumption, the above results appear woefully incomplete. In 1990 the United Nations launched a new index under the inspiration of Mahbub ul-Haq and Amartya Sen, the Human Development Index (HDI). This index, now published yearly under the auspices of the United Nations Development Program, tries to give a more accurate picture of what it means to be poor and what one should pay attention to if the poor are to progress to a better life. The HDI is a combination of three indices: (1) Life expectancy at birth as an indication of a long and healthy life; (2) Mean years of schooling at a given moment plus mean expected years of schooling as a representation of the acquisition of knowledge; and (3) Gross National Income per capita as an indication of a decent standard of living.9

A number of critics have wanted to add a fourth dimension to the HDI and call it IHDI (for ‘Inequality HDI’) on the grounds that inequality reduces the welfare of the poor. Now, in as far as inequality grows from barriers to equal treatment before the law, the addition is fair, but would better be included in an economic liberty index of the sort compiled by the Fraser Institute in Canada or the Heritage Foundation in the United States. However, if the new index is used to enjoin public intervention to undo existing income differences flowing from the operation of the free market, then the aspiration, though understandable, is better achieved by more growth.

The case of India has starkly revealed the difference between the two approaches, one stressing human development, the other economic growth. The polemic has centered around two recent books: one by Amartya Sen and his long-time collaborator Jean Drèze (2013) on India and its contradictions; and the other, Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind Panagariya (2013) on how much growth matters for the poor and how important deregulation is for growth. Sen, when commenting on his book with Drèze, has underlined the need for more public services in India:

The lack of health care, tolerably good schools and other basic facilities important for human well-being and elementary freedoms, keeps a majority of Indians shackled to their deprived lives in a way quite rarely seen in other self-respecting countries that are trying to move ahead in the world.

He extolled the good effects of a program of public intervention in Kérala and even in Bangladesh, a country whose income per capita is markedly lower than India’s but whose index of human development is higher.

See the EconTalk podcast episodes Bhagwati on India and Deaton on Health, Wealth, and Poverty for more on the topics in this article.

Bhagwati, on the contrary, has lamented that the spirit of 1991, the deregulation program of the Indian Government that set India on a much needed growth path, seems to have been lost. Only some states, such as Gujarat, are placing their bets on freeing business and reigning in bureaucracy, with positive results. In his book with Panagariya, Bhagwati called for toppling the ‘Regulation Raj’, the all-encompassing administrative empire left behind by the British.

We cannot emphasize enough that our analysis, while it is addressed to India’s development experience and underlines the centrality of growth in reducing poverty, has clear lessons for aid and development agencies, as well as NGOs that continually work to affect poverty all over the world.

Bhagwati has loudly complained that Sen will not join in battle with him, which is a pity given that the question at stake is so important. In view of Sala-i-Martin’s results recounted above, I think that growth is the strategic variable. International aid, both public and private, can help when it is aimed at the grass-roots, not directed to governments, when it often becomes aid to Switzerland. Wholesale intervention by local officials, even when they are not corrupt, is usually a hindrance to doing business and to supplying public services.10

Sen and Drèze underline what public authorities could do but often don’t. Growth has positive effects but does not address all or most of the needs of the poor. But what if human development proves to be highly correlated with GDP per capita? There is evidence that this may be the case. It seems to me that Sen should acknowledge that freeing the economy and opening it to foreign trade and investment is more effective in the fight against poverty than the administrative remedies he proposes. As the saying goes, ‘better trade than aid’.

The evolution of world inequality 1970-2006

The other statistic we should make explicit in our discussion is the measure of inequality (though it is implied in that of poverty). There are many different ways of measuring this dimension of income distribution and P&S go down a number of them. I shall choose to focus on the Gini coefficient, which is the classical one. When the Gini number is 0 the situation is said to be one of perfect equality; and when 1, perfect inequality.11 Figure 3 shows a steep fall of the Gini coefficient from 1970 to 2006 and therefore reflects a dramatic reduction of inequality in the world. The line shows a hiccup at the end of the 1990s but then steady progress. The authors see this improvement mainly as the effect of the movement of the Chinese population from low productivity agriculture to high productivity cities, a less pronounced rural-urban migration within India, and decided growth in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Incorporating information about the within-country distribution is problematic, however, because data are only readily available in the advanced world. Political circumstances can also affect the trend. Thus there was a large increase in poverty and in inequality when the Soviet Union dissolved and became the Russian Federation. An example of a different kind is that of Nigeria, where for many years the rich got richer while the population in general retreated but recent political reform now seems to have inverted the trend.

It is a well known result in growth economics that countries at different moments of their progress tend to converge onto the rate of growth of the more advanced ones. Nobel Prize laureate Robert Lucas (2009) plotted forty years of growth on the 1960 per capita income of 112 countries. Countries that were poor in that year showed widely scattered subsequent growth rates, from miraculous progress in East Asia to stagnation or negative growth in Africa and Latin America; and countries that were rich in that year showed average rates of growth from 1960-2000 of only around 2%. The resulting picture was a triangle on its side converging on the United State and European Union vertex.12

Lucas then proceeded to relate that convergence with the ‘openness’ of the backward countries. The definition of openness he used is undemanding but still shows up in the growth rates of the most backward of the 112 countries: the closed ones tended to stay put at their 1960 income levels while the open ones grew faster.13

The obsession with inequality in the advanced world

The question of inequality is the source of much confusion among well-meaning critics of the capitalist system. What I have described of the consequences of the free market up to this point is rather positive, I should say. But capitalism is a system that intellectuals love to hate, among salt-water economists, in Ivy League universities of the United States, in the Departments of English, Sociology and Economics of British Universities, not to mention most economists of Continental Europe.

An example of the myopia that affects some of the most distinguished social scientists is the book recently published by Angus Deaton (2013). This Princeton professor is a world famous demographer who has made the measurement of poverty one of his specialties. His new book shows him at his best, especially his use of clear graphs to elucidate complicated concepts and discover hidden realities. It is a story of how large swathes of humanity have escaped poverty, hunger, illness, premature death, and unjust discrimination—and how medical and economic progress is slowly pulling up the whole of mankind so that they can escape a life that is ‘solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short’. The world is decidedly a better place to live in than it was in the past, and Deaton’s analysis of why it is so and how we got here makes his book decidedly worth reading.

The subtitle however is bewildering: “Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality”. Why is inequality always to be deplored? Fair enough if he was dealing only with exploitation, of which there is still a great deal in the world, insofar as the powerful use politics to gain unfair advantages; but not if he is descrying the very force that is materially helping people to become more equal. “Today’s global inequality was, to a large extent, created by the success of modern economic growth” (page 4); and the progress of medicine, he could have added, since it is “not just income, but health too” that is creating inequalities (page 6). Now comes a phrase that indicates a certain confusion of thought: “health inequalities are one of the great injustices of the world today” (page 7). If it is an injustice, what would be just? If it is an injustice, who is to blame? Medical advances cannot be extended immediately to everyone. I still remember that in my youth vitally needed antibiotics had to be purchased on the black market in Spain. It may be the rich who benefit first, but not always. Deaton himself admits that it would be absurd to stop the use of new medical knowledge until it was at the disposal of everyone. The idea that medical services should be free at the point of service, as they are in the United Kingdom, is not self-evidently good for the progress of good health.

Under the influence of Amartya Sen, Deaton defines liberty in the broadest of terms, so that any obstacle to the full realization of individual capacities is an instance of oppression. Individual liberty is “the freedom to live a good life and to do the things that make life worth living”. And he adds, thus unnecessarily stretching the meaning of liberty: “The absence of freedom is poverty, deprivation, and poor health”. (page 2) Should wellbeing be seen as a part of individual freedom? I doubt it. It was Isaiah Berlin who in 1958 memorably said that liberty is to be free from coercion; and he added: “Liberty is liberty, not equality or fairness or justice or culture, or human happiness or a quiet conscience” (page 125)

I would not like to stop anyone from reading Deaton’s last book, full of interesting thoughts and facts on the great escape of humanity from the clutches of poverty, but Deaton, apart from lamenting the persistence of some inequalities, does not make it quite clear when inequalities are to be welcome as being the stepping stones of progress.

The top one percent

The object of the present column is to show what the free market system, in as far as it is allowed to be free, has done for the poor of the world, from the point of view of income, welfare, and equality. When speaking of equality Deaton mainly and mercifully deals with the world as a whole. This leads him to a nuanced view of what the medical and industrial revolutions have done for the poor.

However, the fashion among people of the left in the United States, and in Europe, among the rich with bad consciences gathered in Davos, is of a different hue: they worry about what the market grants the rich and denies the middle classes. So despite anything the defenders of a better life for the poor may say, the topic of the day is spreading inequality.

Proof of this is the Summer 2013 number Journal of Economic Perspectives: it leads with a symposium on inequality inside the nations of the advanced world. That symposium is worth reading to get a feeling for the state of professional opinion among economists.

The articles fall into two camps. The more numerous is the side that demands political redistribution mainly through taxes to correct increasing inequality, especially in favor of the top one percent or top 0.1 percent of the population. The minority defends the distribution thrown up by the market as being acceptably efficient and just.

The interventionists not only point to the increasing income of the very rich but also to the stationary real income of the middle class and the lack of upward mobility, in the United States in particular. Their main argument is that it is unfair to see such a small group of ‘privileged’ people making good; that they really are rent-seekers favored by their political friends; that this inequality creates a danger of instability in advanced democracies; or even that it carries the seeds of the demise of the capitalist system. On this last point, there is a representation in the symposium of the so-named ‘School of Paris’. They maintain, in a Marxist fashion with a dash of Keynesianism, that the dynamics of capitalism condemn it to self-destruction. The head of the school is Professor Thomas Piketty, who with the help of boundless erudition tries to show that under unregulated capitalism the return on capital tends to exceed the rate of economic growth and therefore leads to a reenter economy; and such an economy is condemned to stagnation and decay. The only solution is to tax the rich.14

On the side of those who write in defense of the large gains of the one percent we principally find Gregory Mankiw (2013). He does recount the striking evidence of the growing share of national income obtained by the top percent from 1973 to 2010. Some of it may be due to successful rent seeking, as Bivens and Mishel (2013) say happened in the financial sector. But, says Mankiw, “the key issue is the extent to which the high incomes of the top 1 percent reflect high productivity rather than some market imperfection” (page 35). He underlines the effect of digital technologies leveraging the talent of entertainment stars and service entrepreneurs in multiplying their gains.15 The difficulty of great numbers of the population adapting to new production systems or acquiring the necessary human capital to do well in them must also be part of the explanation; and the competition of the poor of the Third World is a fact but should be generously accepted.

A fitting conclusion to these polemics appeared in the Correspondence section of the December 2014 number of the same review: Robert Solow published a letter criticizing Mankiw, who replied rather sharply but with much good sense.

Conclusion

As long as the improvement of the situation of a member of a society is not at the cost of any other member, I do not in principle see any reason to complain or interfere. In any free society it is crucial to separate the vice of envy from the virtue of emulation.

Alvaredo, Facundo; Atkinson, Anthony B.; Piketty, Thomas; and Saez, Emmanuel (2013): “The Top 1 Percent in International and Historical Perspective”. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 27, nr. 3, Summer, pgs. 3-20.

Berlin, Isaiah (1959, 1969): “Two Concepts of Liberty”, in Four Essays on Liberty. Oxford.

Bhagwati, Jadish and Panagariya, Arvind (2013): Why Growth Matters: How Economic Growth in India Reduced Poverty and the Lessons for Other Developing Countries. Columbia,

Bivens, Josh and Mishel, Lawrence: “The Pay of Corporate Executives and Financial Professionals as Evidence of Rents in Top 1 Percent Incomes”. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 27, nr. 3, Summer, pgs. 57-78.

Dalrymple, Theodore (2001): Life at the Bottom: The Worldview that Makes the Underclass. R. Dee.

Deaton, Angus (2013): The Great Escape. Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Princeton.

Drèze, Jean and Sen, Amartya (2013): An Uncertain Glory. India and its Contradictions. Princeton.

Feldstein, Martin S. (1998): “Income Inequality and Poverty”. NBER, Working Paper 6770.

Kaplan, Steven N. and Rauh, Joshua: “It’s the Market: The Broad-Based Rise in the Return to Top Talent”. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 27, nr. 3, Summer 2013, pgs. 35-56.

Lockwood, B. (1988): “Pareto Efficiency”, The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, vol. 3, pgs. 811-813.

Lucas, Robert E. Jr. (2009): “Trade and the diffusion of the Industrial Revolution”, AER: Macroeconomics vol. 1, nr.1, pgs. 1-25.

Mankiw, Gregory N. 82013): “Defending the One Percent”. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 27, nr. 3, Summer 2013, pgs. 21-34.

Milanovic, Branko (2013): “The return of patrimonial capitalism. A review of Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the 21st century“. MPRA. To be published in the Journal of Economic Literature in June 2014.

Pinkovskiy, Maxim and Sala-i-Martin, Xavier (2009): “Parametric Estimations of the World Distribution of Income”. NBER.

Sachs, Jeffrey D. and Warner, Andrew M. (1995): “Economic Reform and the Process of Global Integration”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (1), 1-95.

Sen, Amartya K. (2002): “The Possibility of Social Choice”, in Rationality and Freedom. Harvard.

Solow, Robert and Mankiw, Gregory (2013): “The One Percent”, Correspondence. Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 28, nr. 1, Winter 2014, pgs. 243-248.

Tooley, James (2009): A Personal Journey into How the World’s Poorest People Are Educating Themselves. Cato.

United Nations (2013): The Millennium Development Goals Report. UN.

“Although poverty, inequality, and growth are three different ways of looking at the same object (the distribution of income), researchers traditionally analyzed the three separately. Growth (of per capita GDP) usually relates to the percentage change of the mean of the distribution. Poverty relates to the integral of the distribution to the left of a particular poverty line. Inequality refers to the dispersion of the distribution.” (page 2) The three questions should therefore be seen as components of the central question of the improvement of human welfare. Let me say that reading this passage was a Eureka moment for me.

Though Sala-i-Martin inclines to income per capita as a measure of poverty, he does check his results with a number of other methods, among them those that rely on surveys. And the overall picture is not so different.

These notional amounts of $1, $1.50 or $2 a day are of course corrected for inflation and purchasing power across different societies.

Thus Deaton (2013), page 184: poverty in an advanced country “is about not having enough to participate fully in society, about families and their children not being able to live decent lives alongside neighbors and friends.” The conclusion for Professor Deaton is that “it is very hard to justify anything other than a relative poverty line” in wealthy countries like the United States. I beg to differ.

See Dalrymple (1990).

Pinkovskiy and Sala-i-Martin approximate the population by fitting the data with a normal or ‘parametric’ distribution bell curve—which is not too far-fetched an assumption when the sample is so large. Sala compares these results with the ‘non parametric’ kernel method after dividing the population in quintiles and finds them very similar.

This is a semi-logarithmic graph, in that it compresses the whole gamut of yearly incomes per head on the x-axis so that the distance between $50 and $500 a year is the same as between $500 and $5,000.

If we reckon that from 1970 to 2006, 617 thousand in the $1a day group must have moved up to the $2 a day group, and that this group was smaller in 2006 by 783 thousand, the gross reduction of the $2 a day must have been nearly 1.4 billion, despite the growth of the world population by nearly 6.5 billion.

Before its reform in 2010 the HDI was a rough measure of the ‘functionings’ of the poor (to use an Amartya Sen concept) or the kind of life they lead at present. The new HDI includes indices of the possibility of a better life for the poor in the future, thus trying to approach what Sen calls the ‘capabilities’ that the poor have. For ‘functionings’ and ‘capabilities’ see Sen’s somewhat different approach in his Nobel Prize lecture (1998, 2002), pages 86-90 and passim.

The disastrous state of public schooling in many states of Africa, India, and China is a sad example of the inefficiency of nationalized services, as witnessed by Tooley (2009).

The Gini coefficient is a probability distribution showing the difference between the line of perfect equality and the observed percentage of total income cumulatively assigned to each percentage of the population, starting from the lowest: as when one says that 5% of total income is received by the lowest 20% of the population and so on upwards. Princeton demographer Angus Deaton (2013, page 187) uses the mathematical equivalent: half the mean difference between two items selected randomly, relative to the average income.

See figure 1 in Lucas (2009 page 2): a “triangular pattern […] familiar to students of growth” reflecting the convergence of the extremes of high and low growth in developing countries towards the US and the EU.

Lucas uses the definition of openness of Sachs and Warner (1995): the country must show effective protection rates of less than 40%; less than 40% of imports must be limited by quotas; no controls or black markets in currency; no export marketing boards of the kind left in place in Africa by the colonial powers; and not be socialist of the East European type. Lucas (2009), page 3.

See Alvaredo, Atkinson, Piketty and Saez (2013). Also of funereal interest is Branco Milanovic’s (2013) review of Piketty’s Capitalism in the 21st Century.

This is also the argument of Steve Kaplan and Joshua Rahu (2013).

*Pedro Schwartz Pedro Schwartz is “Rafael del Pino” Research Professor of at San Pablo University in Madrid where he directs the Center for Political Economy and Regulation. A member of the Royal Academy of Moral and Political Sciences in Madrid, he is a frequent contributor to the European media on the current financial and social scene.

For more articles by Pedro Schwartz, see the Archive.