The Economics of Tax Dodging

By Pierre Lemieux

From one perspective, tax dodging prevents everybody’s tax burden from being pushed higher.

Tax avoidance and tax evasion have been much in the news recently. Inversions (the legal folding of an American company into an overseas holding company to avoid high U.S. corporate tax rates) have been criticized by officials as “unpatriotic.”1 Tax advantages granted by tax-competing governments (Ireland and Luxembourg, for example) are under attack.2 Foreign banks have been harassed into supplying information on American customers.3 Switzerland has been bullied into abandoning its traditional banking secrecy.4

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an intergovernmental research outfit previously known for its high-quality, market-friendly economic research, has been involved in helping member states fight “harmful tax practices” since 1998. Its latest step, on October 29, 2014, was the approval of its protocol for exchange of taxpayers’ information. OECD Secretary-General Alex Gurria declared that “[t]he world is becoming a smaller place for tax cheats.”5 In its November meeting, the G-20 repeated its commitment to fight tax evasion.

Dodging taxes can take two forms: “tax avoidance,” which is legal, as it uses loopholes included (often intentionally) in tax laws; and “tax evasion,” which is illegal. The multifaceted campaign against tax dodging targets both individuals and corporations. Ultimately, of course, only individuals pay taxes.

Is dodging taxes bad? And what explains the recent government outcry? To answer these questions, we need to inquire into the consequences of tax dodging. These consequences, in turn, depend on how government works.

The Orthodox Public Finance Approach

Imagine the following world. The only goods that government produces are public goods. Public goods have two characteristics. First, they are non-rival in consumption: one person’s consumption of the good does not diminish the amount that others can consume. Second, they are non-excludable: excluding people from benefiting from public goods is prohibitively expensive. National defense and public protection are the standard examples. Government determines what budget these public-good activities require and then levies the most efficient taxes necessary to finance them. Each citizen is charged a tax price lower than his valuation of the public goods (and lower than any alternative way to produce them). In brief, the state finds the optimal level of public-good expenditures and then levies the most efficient taxes to finance them.

This is, by and large, the model of orthodox public finance theory. In this model, tax dodging by any individual increases the burden on other taxpayers.

Even if there is unanimous agreement on the ideal level and distribution of taxes, each individual still has an incentive to cheat—to let other people pay their “fair share” while he himself gets a free ride. The higher tax rates are, the greater is the incentive to cheat and the more rigorous, therefore, must be the enforcement.

Tax avoidance is different from tax evasion. The rule of law implies that tax obligations are determined not by the whims of bureaucrats, politicians, or the mob, but by standing and general laws. Whatever one is not obligated by law to pay, one is allowed and expected not to pay. Judge Learned Hand observed eight decades ago: “[A]ny one may so arrange his affairs that his taxes shall be as low as possible; he is not bound to choose that pattern which will best pay the Treasury; there is not even a patriotic duty to increase one’s taxes.”6 What is very troubling in the recent push against tax avoidance (in inversions, for example) is that the government targets behavior that is totally legal. Most individuals regularly engage in tax avoidance by, for example, buying their house or apartment and taking the mortgage interest deduction, instead of renting. Few people would claim that the tax authorities should go after those individuals for taking legal deductions.

The current drive against tax avoidance and evasion does not seem to be due to governments lacking revenues to produce public goods. In fact, taxes are high, both in America and in the rest of the world.

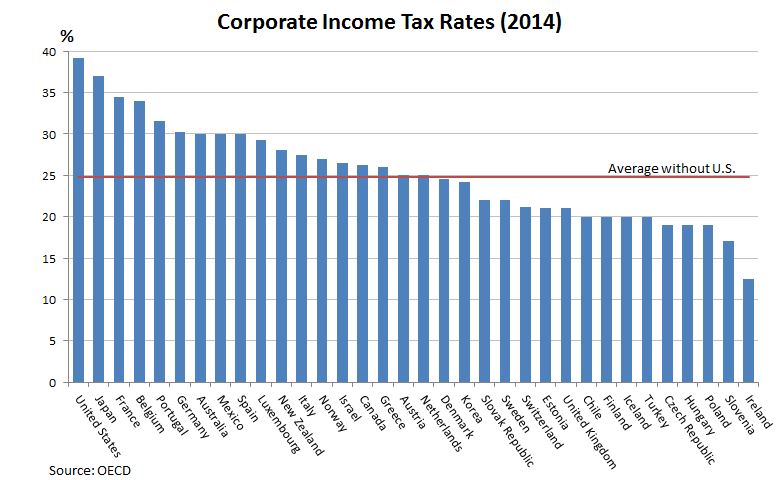

Consider the tax rate on corporate income. The basic corporate tax rate in the United States (federal rate plus “representative” state rate) is 39.1%, compared to 24.8% on average in other OECD countries (see Figure 1).7 However, a more significant datum is the total tax rate, measured as the ratio of all government revenues to GDP. This total tax rate in the United States, 32%, is lower than the average for the OECD countries (42%) and, in fact, is lower than that of any other OECD country except Mexico. Looked at from another angle, the tax take is high everywhere, but not as high in the United States.

A still more realistic measure of the total tax rate is total government expenditures as a percent of GDP; after all, whatever government spends is taken out of the private economy in one way or another—including through borrowing and, thus, future taxes. The ratio of total government expenditures to GDP is 42% in the United States and 45% in the average OECD country.8

However calculated, tax rates are not low, and they have not followed a downward trend. It is instructive to recall what Adam Smith wrote:

No doubt the raising of a very exorbitant tax, as the raising as much in peace as in war, or the half or even the fifth of the wealth of the nation, would, as well as any other gross abuse of power, justify resistance in the people.9

It is true that, in the United States, the total tax rate (calculated as total government revenues as a proportion of GDP) has not increased over the last 15 years, although it had grown nearly continuously before that. But if we look at taxes in constant (2009) dollars per capita, a crisper picture emerges. Total per capita taxes jumped by 438% between 1949 and 2000. In 1965, they stood at $4,935. In the mid-1990s, they reached around $11,000. Since 2000, they have oscillated between $12,000 and $14,000.

For more on tax avoidance, see Supply-Side Economics by James D. Gwartney in the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

Given past trends and the current level of taxes, it would be surprising if tax dodging were not on the rise, in the United States and the rest of the world. The ratio of unreported income to reported income (to the IRS) is estimated at around 23%, up from about 17% in the mid-1990s and 13% in the mid-1960s.10 On the tax avoidance front, more and more Americans are renouncing their U.S. citizenship to escape the international reach of the IRS: the number reached 2,999 in 2013, a 221% increase over the previous year.11 (Unlike most other governments, the U.S. government taxes foreign earnings of American expatriates.)

An Alternative Approach

The long-term increase in tax revenues accompanied by advancing tax evasion and growing repression suggests that orthodox public finance does not provide a realistic model of how government works. How plausible is it that expenditures on public goods have grown so much? In fact, these expenditures make up only a small proportion of government spending: the Department of Defense accounts for only 18% of the federal government’s budget; the Department of Justice, for 0.9%; and the Environmental Protection Agency, for 0.3%. And if the increased expenditures were on public goods, we would have trouble explaining the apparent breakdown of consent about taxes.

Public Choice theory, developed in the last half of the 20th century, provides an alternative model, which can be sketched as follows.12 The individuals who run the state—mainly politicians and bureaucrats—are, like ordinary individuals, motivated by self-interest. Their interests are generally served by expanding the power and scope of government. Politicians do this by providing a large number of private goods and privileges for the benefit of supporting clienteles. Bureaucrats expand the size of their bureaus. We thus observe built-in incentives within the state to collect as much revenue as possible given political and other institutional constraints—to charge what the captive “market” will bear—and then to spend the proceeds on things that benefit those in power and the interest groups whose support they need.

Government maximizes revenues; it does not levy revenues only to produce genuine public goods.

In this sort of model, government is conceived as Leviathan. The name refers to Thomas Hobbes’s all-powerful state, which is what the state becomes if it is not strictly limited by an explicit or implicit constitution. A strong form of the Leviathan model lies in an unorthodox Public Choice theory developed by Anthony de Jasay.13 Orthodox Public Choice uses milder forms of the Leviathan model—as developed, for example, by Geoffrey Brennan and James Buchanan.14

One implication of the Brennan-Buchanan model seems to be that cutting revenues would force the state to reduce its expenditures—the so-called “starve the beast” hypothesis. The hypothesis has been much debated, but supporting empirical evidence has been hard to come by. Episodes of federal tax cuts have not been systematically followed by lower spending.15

There are, however, good reasons for the apparent lack of corroborating evidence. One reason is that tax cuts have been mostly canceled out by later tax increases.16 Another reason could be the exclusion of debt financing from the econometric models that have been used to test the starve-the-beast hypothesis. If the beast is starved of current tax revenues, it may compensate with deficit financing and debt issuance. This is what has happened since the 1960s: the current public debt problem is the result of feeding the beast with borrowing on top of current taxes. The beast was never really starved.

This raises the possibility that starving Leviathan through cuts in tax revenues would now work better since the federal government’s leeway to borrow has been much reduced. Any entity that can neither earn nor borrow more and has no savings must spend less.

The implications of these considerations for our topic are momentous. If Leviathan maximizes its revenues (both tax revenues and debt financing) given the political and economic constraints it faces, tax avoidance and, especially, tax evasion have the effect of tightening these constraints. Harold Demsetz, a professor of economics at UCLA, argued that when the government sector reaches beyond 25% of GDP, the underground economy—that is, tax evasion—starts to grow significantly.17 Tax avoidance probably grows too, as it becomes more profitable to hire accountants and tax lawyers and even to move abroad. Demsetz conjectured that when the proportion of government revenues reaches 40% or 45% of legal GDP, the underground economy will grow in step with the state’s effort to increase taxes, so that the government take will increase only as a proportion of legal GDP but will remain constant as a proportion of total (legal plus illegal) GDP.

In this perspective, tax evasion and avoidance provide a built-in brake on Leviathan’s expansion. Tax dodging reduces and eventually eliminates the state’s capacity to increase its revenues. Thus, it removes incentives to further exploit taxpayers and prevents everybody’s tax burden from being pushed higher—a conclusion diametrically opposed to standard public finance thinking.

Is Tax Dodging “Bad”?

I am now in a better position to answer my two opening questions: Why the current campaign against tax dodging? And is tax dodging bad?

In traditional public finance, the answer to the first question must be that the state needs more revenues because essential expenditures continue to increase; and the public debt cannot grow much more without triggering cuts in credit rating, investor fears, and a rise in the rate at which the government borrows. The Public Choice model I have used provides a different answer: as it becomes more difficult to increase tax revenues and borrowing gets constrained, Leviathan resorts to reducing the taxpayers’ capacity to exit the system through tax evasion or “aggressive tax planning.” The tax authorities grab more power and embark on campaigns against tax dodging. The phenomenon is not new, but one expects it to spread as taxes and the public debt reach higher levels.

Whether dodging taxes is “good” or “bad” is a value judgment that takes us outside the field of economics. But surely one’s value judgment will depend, at least partly, on the consequences of tax dodging. From the vantage point of orthodox public finance, dodging taxes is naturally considered bad because the burden of financing essential public expenditures is transferred to compliant taxpayers. Bad taxpayers free ride on good ones, who become the suckers. In our public choice model, however, dodging taxes provides a built-in check on Leviathan. Tax dodgers are not free-riding on other taxpayers; on the contrary, taxpayers benefit from tax dodgers’ resistance. They benefit because potential tax resistance prevents Leviathan from increasing everybody’s tax burden even more.

The two approaches suggest very different solutions. In one case, increased tax dodging must be met with more repression. In the other case, the best response consists in implementing effective tax cuts and other limits on Leviathan’s resources.

I leave it to my readers to decide for themselves what are the most realistic approach, the best moral judgment, and the most desirable solution.

Andrés Martinez, “Obama Is Wrong. In Defense of Burger King and Companies Fleeing the IRS,” Washington Post, September 23, 2014, at http://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2014/09/23/obama-is-wrong-in-defense-of-burger-king-and-companies-fleeing-the-irs/.

See, for example, “MEPs Call for EU Tax Haven Probe as Luxembourg Furore Grows, Financial Times, November 11, 2014, at http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/3efc5a02-69be-11e4-9f65-00144feabdc0.html#axzz3MSjhKVUD; and “Dublin to Shut Double Irish Corporate Tax Loophole Next Year,” Financial Times, at http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/161322e4-53af-11e4-929b-00144feab7de.html#axzz3NM5wbsHI.

Robert W. Wood, “51 Nations Swap Offshore Account and Tax Data, FATCA On Steroids,” Forbes, October 30, 2014, at http://www.forbes.com/sites/robertwood/2014/10/30/51-nations-swap-offshore-account-tax-data-fatca-on-steriods/print/.

See, for example, “Swiss Banks Say Goodbye to a Big Chunk of Bank Secrecy,” Wall Street Journal, July 1, 2014, at http://blogs.wsj.com/moneybeat/2014/07/01/swiss-banks-say-goodbye-to-a-big-chunk-of-bank-secrecy/; and “Swiss Bank Accounts: Not So Secret Anymore,” Bloomberg, July 28, 2014, at http://www.bloombergview.com/quicktake/swiss-bank-accounts.

“Major New Steps to Boost International Cooperation Against Tax Evasion: Governments commit to implement automatic exchange of information beginning 2017,” OECD, October 29, 2014, at http://www.oecd.org/newsroom/major-new-steps-to-boost-international-cooperation-against-tax-evasion-governments-commit-to-implement-automatic-exchange-of-information-beginning-2017.htm.

Quoted by Henry Ordower, “The Culture of Tax Avoidance,” Saint Louis University Law Journal 55-1 (Fall 2010), p. 47, at http://www.slu.edu/Documents/law/Law%20Journal/Archives/Ordower_Article.pdf.

OECD Tax Database, Table II.1, at http://www.oecd.org/tax/tax-policy/tax-database.htm#C_CorporateCaptial.

Tax and expenditure data are from the OECD’s System of National Accounts for 2011.

Smith, Adam (1763), Lectures On Jurisprudence, R. L. Meek, D. D. Raphael and P. G. Stein, Eds., Vol. V of the Glasgow Edition of the Works and Correspondence of Adam Smith (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1982).

Edgar L. Feige and Richard Cebula, “America’s Underground Economy: Measuring the Size, Growth and Determinants of Income Tax Evasion in the U.S.,” Munich Personal PePECc Archive, 2011, at http://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29672/1/MPRA_paper_29672.pdf.

Robert W. Wood, “Many Americans Renounce Citizenship, Hitting New Record,” Forbes, August 7, 2014, at http://www.forbes.com/sites/robertwood/2014/08/28/u-s-hikes-fee-to-renounce-citizenship-by-422/.

On Public Choice theory, see my “The Public Choice Revolution,” Regulation 27-3 (Fall 2004), pp. 22-29, at http://www.farmjournalmedia.com/assets/import/files/v27n3-2.pdf.

Anthony de Jasay, The State (1985) (Liberty Fund: Indianapolis, 1998), available at http://www.econlib.org/library/LFBooks/Jasay/jsyStt.html.

Geoffrey Brennan and James Buchanan, The Power to Tax: Analytical Foundations of a Fiscal Constitution (1980) (Liberty Fund, 2000), available at http://www.econlib.org/library/Buchanan/buchCv9.html.

See Michael J. New, “Starve the Beast: A Further Examination,” Cato Journal 29-3 (Fall 2009), pp. 487-495; Christina D. Romer and David H. Romer, “Do Tax Cuts Starve the Beast? The Effect of Tax Changes on Government Spending,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2009 (Spring), pp. 139-200; and Stephen J. Davis and Jeffrey A. Miron, “Do Tax Cuts Starve the Beast? The Effect of Tax Changes on Government Spending—Comments and Discussion,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 2009 (Spring), pp. 201-214.

Romer and Romer, op. cit., pp. 177-178.

Harold Demsetz, Economic, Legal, and Political Dimensions of Competition (North Holland, 1982), pp. 120-123.

*Pierre Lemieux is an economist affiliated with the Department of Management Sciences of the Université du Québec en Outaouais. He is the author of several books and articles. His latest book is Who Needs Jobs? Spreading Poverty or Increasing Welfare (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014). E-mail: PL@pierrelemieux.com.

For more articles by Pierre Lemieux, see the Archive.