Mancur Olson

1932-1998

Mancur Olson was an American economist who had pathbreaking insights about collective action, the rise and decline of national economies, and the fortunes of Communist and post-Communist countries.

The Logic of Collective Action

Olson’s first major work, The Logic of Collective Action, published in 1965, examined what is required for collective action to succeed when the number of people in the “collective” is large. Collective action, he noted, is subject to the free-rider problem: many of the people who would gain from the collective action would get the benefits even if they didn’t bear any of the costs. His argument was not that collective action would fail. Rather it was that those who organize such action need to find some way of giving incentives for people to join in paying for the collective action. Olson called this the “by-product theory.” An organized group would sell something to members and use any above-normal profits to lobby. Lobbying is thus a by-product of the good or service being sold.

Olson gave as an example the Illinois Farm Bureau, which lobbied the federal government for subsidies. How did it succeed? It provided low-price auto insurance to farmers. Olson argues that the insurance companies that the Farm Bureau created “may have profited from the fact that their clientele was largely rural, and thus at times probably less apt to drive in congested areas and be involved in traffic accidents.” An economist’s kneejerk reaction to that argument might be that some other insurance company could provide an even lower premium by not having to price to recover the resources for lobbying. But it’s possible that insurers missed that market and it took the Farm Bureau to notice it. Olson notes that both State Farm and Nationwide started by selling insurance to farmers in affiliation with the Farm Bureau.

In discussing Olson’s work, Avinash Dixit writes:

Most of his research can be seen as the exploration and application of one idea, but that idea was very big indeed. It was the problem of collective action, namely how individuals acting in their private interest can fail to secure the provision of goods or services that are collectively in the interests of all. In other words, Olson’s focus was on nothing less than what is arguably the most important class of failures of Adam Smith’s invisible hand.[1]

But Olson’s work on collective action was more general than that. Olson also wrote at length about how people acting in their own self-interest can fail to secure policies that hurt the overall interest of a society. Olson studied various lobbying groups, many of which pushed for restrictions on competition that created gains for the group that were less than the losses to the rest of society. So when such lobbies did not come about, Adam Smith’s invisible hand, far from failing, actually succeeded.

The Rise and Decline of Nations

Couldn’t there be so many lobbies each pursuing its own members’ self-interest that the overall effect could be slower growth of economic output and economic well-being? Yes, and that was Olson’s major insight in his next pathbreaking book, his 1982 The Rise and Decline of Nations. Olson asked why some nations’ economies grew faster than others. He noted that of course one could account for much growth by examining the data on capital accumulation and technical advances. But Olson regarded that as unsatisfactory. He pointed out that simply doing what economists call “growth accounting” doesn’t answer a more fundamental question: why, for example, does capital accumulate and why is there more innovation in one country than in another? Olson made his point with a nice metaphor. Economists who do growth accounting “trace the water in the river to the streams and lakes from which it comes, but they do not explain the rain.” He wanted to “explain the rain.”

In Rise and Decline, Olson was reasonably successful at doing so. In laying out his argument, he drew on his insights about collective action. Small groups will often lobby for special privileges that benefit them but hurt the public. As countries age, more lobbies will crop up and each of them will, at least slightly, reduce overall well-being. So, for example, steel producers lobby for restrictions on steel imports. Those restrictions reduce the supply of steel and cause prices to rise. That hurts all users of steel. People in other industries, seeing the steel industry’s success, will form their own lobbies to restrict, say, the importation of tires. As this progresses, the economy may not literally stagnate but it becomes sclerotic and its growth rate falls.

If his argument were right, stated Olson, then “countries whose distributional coalitions have been emasculated or abolished by totalitarian government or foreign occupation should grow relatively quickly after a free and stable legal order is established.” He pointed to the economic growth miracles of both Japan and Germany after World War II. That war disrupted normal interactions in those two countries so much, he argued, that many special interest groups were destroyed. In both countries, therefore, they didn’t have time or the connections to organize quickly to form their lobbies to push for government-enforced monopolies.

Olson argued that another country whose experience fit his hypothesis was France. World War II, even with the German occupation, did not disrupt France or destroy its capital base the way it did to Germany and Japan. But ideological fissures, argued Olson, “divided the French labor movement into competing communist, socialist, and catholic unions.” That division, often in the same workplaces, argued Olson, prevented any particular union “from having an effective monopoly of the relevant work force.” As a result, labor unions in France had less of a harmful effect on the economy than one might have expected if one focused only on the high percent of the French labor force that was unionized.

Olson admitted that Sweden, whose economy grew well after World War II, would seem to be a counterexample to Olson’s theory. It avoided the war and, therefore, did not have a massive destruction of its lobbying organizations. But, he argued, Sweden’s economy actually fit his model. The reason is that Sweden’s lobbying organizations were “encompassing.” In other words, they were so inclusive that they took account of the damage that would be done by narrow policies aimed at monopolizing specific industries or labor forces. Olson pointed out that practically all unionized manual workers belonged to “one great labor organization.” Employers’ organizations were also inclusive.

Olson noted that his model of nations’ economic growth implies that free trade is even more important than economists have shown using static analysis. Economists since David Ricardo have shown that free trade causes people in each nation to produce the goods and services in which they have a comparative advantage, thus leading to greater overall output and economic well-being. But Olson noted a further benefit of free trade: it undermines cartelization of firms and indirectly reduces monopoly power in labor markets. Olson also notes that allowing more immigration reduces the monopoly power of labor. Both free trade and relatively free immigration, therefore, make economies less sclerotic.

Olson tested his model not just by looking at Europe and postwar Japan but also by examining non-Western countries in other eras. He pointed out that Japan had high economic growth after the Meiji restoration in 1867-68. Why? Olson argued that it was because the Meiji restoration deposed the shogun, thus reducing the power of vested interests that were tied to the shogunate. It also reduced the power of the feudal daimyo (war lords), causing the related restrictions on trade to fall. Another factor, he argued, was the imposition of free trade on Japan by the British and other Western governments. Japan’s government was limited to tariff rates of no more than 5 percent. The Japanese, noted Olson, referred to this imposition as “humiliating.” Olson commented, “Lo and behold, the Japanese were humiliated all the way to the bank.”

Another country whose experience, sadly, fit Olson’s model was South Africa, first with the Colour Bar of the early 20th century and then with Apartheid, which began in 1948. The Colour Bar’s restrictions on the number of African and Asian workers that mine owners could hire, restrictions lobbied for by higher-paid workers of European descent, hurt economic growth. In his discussion of South Africa, Olson drew on the pathbreaking work of W. H. Hutt in his 1964 book, The Economics of the Colour Bar.[2]

Drawing on his evidence from South Africa and other countries, Olson challenged a view articulated by Arthur Okun in his famous 1975 book, Equality and Efficiency: The Big Tradeoff. Olson pointed out that Okun simply took it for granted that government is an egalitarian force that reduces the inequality created by free markets. Olson countered that that assumption “is the opposite of the truth for many societies, and only a half-truth for the rest.” He pointed to the fact that government restrictions on hiring black labor were what caused some black workers in South Africa to be paid less than 10 percent of what white workers were paid for doing slightly different jobs that required approximately the same skill. In free markets, noted Olson, such wage differentials could not persist. The reason is that profit-maximizing employers would hire black workers, driving their wages much higher. And most of the world’s countries, he noted, were unstable and poor and in most of them governments restricted trade and investment, keeping them poor and generating “colossal inequalities.”

Power and Prosperity

Olson’s last book, published in 2000 after his death, was Power and Prosperity. In that book, he focused on how the institutions of government help or hurt long-run prosperity. Like many contributors to public choice, Olson regarded government through a distinctly non-romantic lens. He likened government to a bandit: like a bandit, government takes resources from people by force. To analyze further, he introduced his famous metaphor of a roving bandit or a stationary bandit. The good news is that even autocratic governments are often stationary bandits. They plan to be around for a long time and, therefore, have an incentive to care about what percentage of people’s resources they take. The more they take, the less is the people’s incentive to produce. If autocratic governments don’t plan to be around for a long time, possibly because the autocrat will die soon or there’s a high probability of the autocrat being overthrown, then the autocrat is like a roving bandit. He or she has less reason to be concerned about future production and, therefore, will tax more heavily. Olson wrote that in any society with an autocratic government, “an autocrat with the same incentives as a roving bandit is bound to appear sooner or later.”

One implication of Olson’s model of autocracy, Olson noted, is that it makes sense for people to say, “Long Live the King.” If the king expects to live a long time, he is more like a stationary bandit than a roving bandit.

Olson also laid out various conditions for autocracy to yield to democracy. One key condition is that there be a balance of power among those who overthrow an autocracy so that no one has much of a chance of being an autocrat. Once established, representative democracies have an incentive to enforce property rights and to enforce contracts.

In the economics literature, Gary Becker and Donald Wittman claimed that the policies that emerge from a democracy are efficient. The reason, they argued, was that if such policies weren’t efficient, they would be replaced by policies that had less deadweight loss because the gainers from the replacement could compensate the losers. Olson argued that the theory was utopian because it failed to explain why there are such bad outcomes in many countries. Olson used his own earlier contribution to the theory of collective action to explain why we often get bad outcomes: if the losers from an inefficient policy number in the millions, it’s difficult for the losers to get together and change the policies. Each loser has only a small incentive to do so and even if he succeeds, will get few of the benefits from changing the outcome.

In the second half of his book, Olson creatively applied his thinking to many important issues. One example has to do with inequality of wealth. Many people think wealth inequality is bad. Economists understand that there’s a tradeoff: the more governments allow inequality that results from productive activities, the more productivity there will be. Olson noted another benefit of wealth inequality, namely that it helps maintain law and order. He wrote, “When theft and enforcement of contracts are at issue, the more substantial and wealthier interests will normally be on the side of enforcing the law.” He also pointed out that the more that contract law is enforced, all else equal, the lower interest rates will be because debt contracts are among the contracts that are enforced.

Olson’s major insight in the second half of the book was about how Stalin managed to be a stationary bandit in the Soviet Union while still confiscating a huge amount of the wealth. By nationalizing land and virtually all forms of capital, Stalin took for the state a large part of the wealth created. He also kept wages artificially low for a given position and set of skills, while having a fairly low marginal tax rate. The wealth effect of this policy was that because people were poorer than otherwise, they demanded less leisure, which is, after all, a normal good, and thus worked more. The substitution effect of having low rather than high marginal tax rates was that people also worked more. But over the long run, Olson pointed out, managers, bureaucrats, and workers “shared control . . . over the state enterprises that were the principal source of tax receipts.” By the late 1980s, “virtually no resources were passed on to the Soviet government.” The most important factor behind the collapse of communism, Olson concluded, “was that the communist governments were broke.”

Communism, moreover, gave entrepreneurs very little incentive to replace or reallocate capital. So when communism ended, what was left of the capital stock was a very low-value carcass. Olson cited a 1991 study[3] by George Akerlof, et al., that found that “only 8 percent of the East German workers [in East German conglomerates] were producing goods whose value in international markets covered even the variable costs” of production. Olson also noted that because East Germany’s economy was thought to be the most successful of the European communist economies, the Soviet Union was probably even in worse shape. The low value of the capital stock, argued Olson, helped explain why managers and workers in large state enterprises resisted privatization: “their enterprises could not be viable in a competitive marketplace and would not be maintained in a rational economy.”

Olson concluded by noting that markets that require little capital will always crop up even in the poorest economies because of gains from trade. But, he wrote, strong enforcement of property rights and contracts is required to make people willing to invest in long-term capital. “Rather than being a luxury that only rich countries can afford,” he wrote, “individual rights are essential to obtaining the vast gains from” sophisticated transactions.

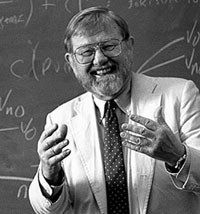

Olson’s Background

Mancur Olson was born in Grand Forks, North Dakota in 1932 and was raised on a farm in Buxton, North Dakota. He earned his B.S. degree at North Dakota State University in 1954 and a Ph.D. in economics from Harvard University in 1963. While in the U.S. Air Force, he lectured in economics at the U.S. Air Force Academy and then became an assistant professor at Princeton University in 1963. From 1967 to 1969, he was a deputy assistant secretary at the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. In 1969, he became an economics professor at the University of Maryland in College Park, Maryland. He was on the faculty there until his death in 1998.

About the Author

David R. Henderson is the editor of The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. He is also an emeritus professor of economics with the Naval Postgraduate School and a research fellow with the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. He earned his Ph.D. in economics at UCLA.

Selected Works

1965: The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Harvard University Press.

1982: The Rise and Decline of Nations: Economic Growth, Stagflation, and Social Rigidities. Yale University Press.

2000: Power and Prosperity: Outgrowing Communist and Capitalist Dictatorships. Basic Books.

Footnotes

[1] Dixit, Avinash: “Mancur Olson—Social Scientist,” The Economic Journal, 1999 (June): F443-452.

[2] Hutt, W.H.: The Economics of the Colour Bar, Merritt and Hatcher, 1964.

[3] Akerlof, George, Andrew Rose, Janet Yellen and Helga Hessenious: “East Germany in from the Cold: The Economic Aftermath of Currency Union.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1991: 1-87.

Related Entries

Related Links

David Skarbek on Prison Gangs and the Social Order of the Underworld, an EconTalk podcast, March 30, 2015.

Katherine Levine Einstein on Neighborhood Defenders, an EconTak podcast, December 14, 2020.