…it is right to expect high growth in future if the economy is depressed now.

I’m not writing about that quote, since Cushman and

Greg Mankiw have done a good job on that one. I’m writing about this claim, that when we started using unemployed capital again we’d start building GDP as well:

And yes, we can expect fast growth if and when that capacity comes back into use.

Even in context, Krugman doesn’t define “that capacity” clearly but he does use the expression “capacity utilization.” So I pulled down the widely-used

capacity utilization index to see if, post-crisis, the old relationship between capacity utilization and GDP growth still holds true.

Spoiler alert: It doesn’t.

In the past, there was quite a strong relationship between changes in capacity utilization and short-term GDP growth, especially if you leave out the service sector (which is usually stable anyway). So

Krugman’s prediction really was based on long-term experience. A

good 1996 paper on capacity utilization by two Fed economists notes:

The correlation between annualized changes in the real output of goods and structures and the Federal Reserve’s index of capacity utilization for manufacturing, the main goods-producing sector, is about 0.9. In short, capacity utilization in manufacturing is indicative of the cyclical state of the overall product market…

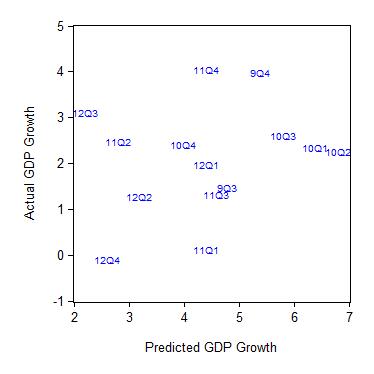

I estimated the post-1967 relationship between capacity utilization and GDP growth on a quarterly basis, and it’s usually quite strong (correlation = +0.7). Then I checked to see if post-crisis the usual relationship has held: It hasn’t.

Just looking from the 3rd quarter of 2009 onward–as soon as growth returned–it turns out that in 13 out of the 14 quarters, GDP growth is below the predicted level (Q3 of 2012 is the big success). On average, GDP growth is half of the predicted growth rate.

[OLS estimate: Predicted GDP Growth = 2*(Change in Capacity Utilization) + 2.8. Estimated on quarterly data 1967-2012. Results reported at annualized rates.]

It’s not just that the relationship between capacity utilization and growth is noisier than it used to be before the crisis: It’s that growth has

consistently been less than you would’ve expected based on how many unused machines got turned back on in 2009 and 2010. Part of the story is that the service sector took a hit after the crisis, so it wasn’t the usual stabilizing force.

So during the crisis we stopped using some machines, then we went back to using them but we didn’t produce the usual amount of GDP growth overall. The recovery has been good for capital, mediocre for GDP and worse for workers.

Apparently, one doesn’t often apologize for forecast errors these days–nice people don’t need to read the apologies and mean people will just gloat–and in any case Krugman might be embracing a lesson of his inaccurate forecast all the same. Now he’s writing about the

rise of the robots. Perhaps the workers are

ZMP but the capital is not.

READER COMMENTS

Keith Eubanks

Feb 11 2013 at 10:51am

Has capacity utilization in recent years gone up because people are using more machines or because there are fewer machines to use? Utilization is a ratio, which side is moving?

Patrick R. Sullivan

Feb 11 2013 at 11:28am

Or, maybe, just maybe, Obamanomics hasn’t worked?

Julien Couvreur

Feb 11 2013 at 12:07pm

If I had to guess, I’d say “that capacity” would reference idle resources, including labor. Isn’t that a central focus of Keynesians?

John Hall

Feb 11 2013 at 12:32pm

I’ve looked into capacity utilization in the past. It is connected with industrial production so that you can back out a series that is effectively capacity, in the same index as IP, (ignoring seasonal adjustment issues, CU is NSA, IP is SA in my data). The capacity index has a 30% correlation with the non-residential (business) investment quantity index since 1968 when the capacity utilization data is available. It is around 20% over the past 40 quarters. However, there is also evidence that the capacity index and the investment series above are cointegrated (and this appears to be stable). Industrial production is also cointegrated with business investment, but the coefficient is more significant for capacity than IP.

RPLong

Feb 11 2013 at 1:01pm

I always liked the parts in Human Action that dealt with capital utilization after recessions. Capital can be put back to use, but it will do so at a lower level of efficiency. It either has to be converted into a new state in order to be used, or it must be used for a purpose other than the original intended purpose.

My belief in general is that as history progresses, economies become more specialized. So, I would expect that this relationship to continue to deteriorate. Hypothetically I suppose it would eventually converge to zero, although it is unlikely that anything the actually had value would ever get to that point.

Bryan Willman

Feb 11 2013 at 6:34pm

A part of the economy I follow informally is rife with stories that go like this:

——————————————

Before the recession we had 12 machines and 153 people and we made X parts a year for Y$.

Due to the pressures of the recession, we now have 13 machines (9 the same as before) and 67 people and we make 2X parts a year for 1.5*Y$.

Our margins are up, business is good!

——————————————

But of course employment, and the basic part of AD that comes from it is down. GDP as measured by $ in motion is up less than the real physical output.

I don’t know if all of these sorts of “stories” add up to something that matters for the economy as a whole or not.

But any business that makes the same or more output, with fewer people lower costs (so less money to direct employees and less money to suppliers), perhaps while charging less for the output, will improve physical wealth while *depressing* GDP and employment (at least directly.)

All of which makes me wonder if “productivity”, GDP, or “capacity” actually mean anything on a macro level.

Tim Worstall

Feb 12 2013 at 5:06am

A slightly odd idea.

OK, so, capacity utilisation and GDP usually move closely together. We’ve a gap now though.

So, what about the idea that capacity itself ages? That the longer it is unemployed the less employable it is?

We certainly think this is true of unemployment: those out of work for more than 2 years find it much, much more difficult to get a job than those out of work for two weeks for example.

And we could extend this to machinery perhaps. A lathe, or tractor, or (most especially!) a chip fab plant, might have been just the thing in 2007. But in 2013 they’re past it, old tech. Sure, they’ve not been used for a few years, but they’re just not up to current production/productivity standards.

So the mismatch is (in part at least,) because of the length of time the capacity has been unused.

Our problem is that to check this we’d need to look at the last time we had this long a slow down. The 1930s. And I’m not sure that the statistics exist for us to be able to check it.

Please do note this is purely a surmise. But that we’re still listing 2007 stuff as capacity when 2007 stuff isn’t really capacity at all might be part of it.

marcus nunes

Feb 13 2013 at 9:40am

Garett, I think there is a growth/level problem in the analysis.

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2013/02/12/breaking-relationships/

Michael Floxo

Feb 16 2013 at 3:20pm

Interesting analysis – there is a simple explanation though. In the modern world capacity is no longer fixed. Rentiers (the owners of capital) have been progressively moving productive capital out of the US (capital rich = low rents) to the rest of the world (capital scarce = high rents). This shrinks the production possibility frontier (ppf) at home while expanding the ppf of foreign. Your data is simply picking up this international capital transfer, which has increased in recent years.

Comments are closed.