The college premium skyrocketed over the last three decades. B.A.s now out-earn high school grads by 70-80%.* College graduation, in contrast, barely rose. In econospeak, the supply of college graduates looks bizarrely price-inelastic.

Over the last two months, I’ve read virtually everything ever written on this puzzle. All of the compelling stories converge on a single factor I’ve emphasized for years: The return to trying to get a degree is far lower than the return to successfully getting a degree. Why? Because marginal students routinely fail to graduate. The single best paper on this theme: “The Education Risk Premium” by Janice Eberly and Kartik Athreya.

Eberly and Athreya begin by spelling out the puzzle:

When measured by the ratio of hourly wages of skilled to unskilled workers, the college premium increased by nearly 20% between 1980 and 1996 (see Autor, Katz, and Krueger (1998)). However, enrollment did not respond substantially. Over the period 1979-2005, even though the fraction of young adults (29 years and younger) with a college degree rose by 9 percentage points (23% to 32%), the increase in male enrollment accounted only for one percentage point (Bailey and Dynarski (2009)).

Quick version of their solution: Expected returns heavily depend on graduation rates – and graduation rates heavily depend on students’ pre-existing academic ability.

The presence of failure risk generates asymmetric changes in the net return to college investment: those with low failure risk see a large increase in expected returns, but are inframarginal because they will enroll under most circumstances. Those with high failure risk see a much smaller increase in expected returns, and hence remain largely inframarginal.

Let me illustrate. Suppose you’re at the 90th-percentile of high school graduates, so your probability of graduating college if you enroll is around 90%. When the college premium ascends from 50% to 70%, your expected premium goes from 45% to 63%. In plain English, the payoff goes from very good to excellent. Either way, enrollment is a no-brainer.

If instead you’re at the 25th-percentile of high school graduates, your probability of graduating college if you enroll is around 20%. When the college premium ascends from 50% to 70%, your expected premium goes from 10% to 14%. In plain English, the payoff goes from really crummy to crummy. Either way, non-enrollment is a no-brainer… especially when you dwell on the fact that colleges don’t refund drop-outs’ tuition, much less the earnings and work experience they forfeited to attend.

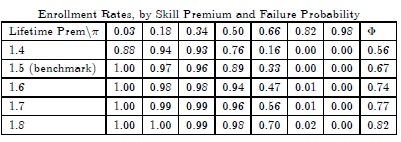

Eberly and Athreya simulate college enrollment under a range of assumptions about the college premium and the completion probability. The right-most column shows the overall fraction of each cohort of kids

that enrolls in college as a function of the college premium. Here is wisdom:

[W]ell-prepared enrollees face low failure risk and so already receive a high rate of return from college under any skill premium in the approximate vicinity of the current one. Similarly, the ability of the skill premium to meaningfully alter mean returns for the ill-prepared is minimal. The only remaining question is then: how large is the set of marginal households? The answer provided by the model is: not very big.

My favorite feature of Eberly-Athreya: Their story readily generalizes to other weighty life choices widely seen as “no-brainers.” Conventional wisdom condemns dropping out of high school. After all, standard estimates say that finishing high school raises your income by 50%. For good students, it’s easy money. For stereotypical “bad students,” though, it’s hard money – or a waste of money. Why? Because when bad students attend high school, their probability of graduation – and their expected return – remains fairly low.

The same holds for marriage. The economic benefits of stable marriage are massive. But as Charles Murray explains, the probability of stable marriage varies widely by social class. Divorce rates for the working class are about four times as high as for professionals. Marginal brides and grooms therefore face a high probability of marital failure – and can reasonably fear that marriage will make them worse off despite its palpable benefits.

To be fair, Eberly and Athreya are not the first or only education researchers to highlight the chasm between ex ante and ex post returns to education. But as far as I can tell, no one makes the logic clearer. If anyone taunts, “So your kids should go to college, but other people’s kids shouldn’t,” the honest answer is “Don’t shoot the messenger – or his kids.” The numbers don’t lie: College is a great investment for great students, a mediocre investment for mediocre students, and a bad investment for bad students.

* This is seriously inflated by ability bias, but over half of the effect looks causal.

READER COMMENTS

Bostonian

Feb 13 2014 at 8:27am

“Because when bad students attend high school, their probability of graduation – and their expected return – remains fairly low.”

There may be enough grade inflation in high school that someone with an IQ as low as 80, too low to master a real high school curriculum, can graduate as long as he attends school every day and avoids getting into trouble. There was a recent CNN article “Some college athletes play like adults, read like 5th-graders”. Those athletes graduated from high school.

Employers use the high school diploma as a signal that you went to school (almost) every day and were not (too) disruptive, not just as an indicator of academic achievement.

Can’t low IQ students be classified as special-ed and be somehow pushed through?

At the societal level I think the high school diploma ought to certify substantial academic achievement (in math, say mastery of Algebra I), but if I had a dull kid, my wife and I would do everything possible to get him a high school diploma, since its absence would really hurt him.

Shane L

Feb 13 2014 at 8:35am

Well said. Some of my classmates dropped out of school early, but I feel it was little loss to them since they were learning very little in school. Instead they got apprenticeships or entered the workforce doing things they were more interested in pursuing. Another positive effect is that their absence from school was helpful for the rest of us since they were often disruptive and unruly in school. They always have the chance to go back as adults and get their school qualifications, now with a sense of purpose.

David R. Henderson

Feb 13 2014 at 9:24am

@Bryan,

Suppose you’re at the 90th-percentile of high school graduates, so your probability of graduating college if you enroll is around 90%.

I don’t understand the “so.” Are you saying that one follows from the other? I don’t see why.

Joshua Macy

Feb 13 2014 at 10:02am

@David I’m pretty sure the “so your probability” is referring to some data Bryan is looking at, hence the later bit about 25th-percentile HS graduates probability of graduating college is 20%.

Aaron Zierman

Feb 13 2014 at 10:14am

This makes a lot of sense. One thing I might add is the rising cost of college. Doesn’t this increase the risk and offset some of the potential gains?

Sahr Mondeh

Feb 13 2014 at 10:42am

Academic ability works just fine in terms of the graduation rate or the investment into earning a degree.It does not necessary add up that a bad high school student does not get into college and become an excellent student. We can look at certain factors like responsibility for loans, difference in environment, ones view of life as it relates to age and thought process at a given time, personal and family experience etc.. Going to college is a worthy investment if you are confident you can handle it but some people don’t need college to be very successful in life. Hence goes the saying “school is not for everybody”. College fees are skyrocketing and it is a serious deterrent to many folks. They are scared of the debt so they just say I cannot afford it. Look at it from this twist as noting that, fees are too for some smart kids to afford college.

Humberto Barreto

Feb 13 2014 at 12:54pm

So the 1/3 of HS grads that don’t enroll in college optimized and made the correct choice. That could be, but how about this from Hoxby and Avery:

“We show that the vast majority of low-income high achievers do not apply to any selective college.” http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/spring%202013/2013a_hoxby.pdf

H&A observe really smart, but low income HS grads making very bad choices (they could go to way better AND cheaper — after fin aid — schools) so that makes me want to focus on information as a critical issue.

Do we really believe that the 1/3 of HS grads that chose not to attend college have the correct probabilities and expected returns?

[short url replaced with full url. Please do not use shortened urls on EconLog. –Econlib Ed.]

Andy Harless

Feb 13 2014 at 2:17pm

This post doesn’t seem to answer the question of why there are so few marginal households. Do I need to read the whole paper to figure that out? I would expect the distribution of academic ability to be close to normal, and the normal distribution is still pretty dense at the 30th percentile (corresponding approximately to the marginal college student given enrollment rates). So I would expect that there are still a lot of people whose chance of graduating is high enough to make going to college advantageous if the return to graduation is high but low enough to make it disadvantageous if the return to graduation is low. Yet we apparently see very little increase in male enrollment when the return rose. Maybe Eberly and Athreya have a model that can explain why this is, but the reason is not apparent to me from the this blog post.

ed

Feb 13 2014 at 2:45pm

Interestingly, whites, blacks, and Hispanics apparently enroll in college at about the same rates:

http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2013/09/04/hispanic-college-enrollment-rate-surpasses-whites-for-the-first-time/

On the other hand, there is a substantial gap in completion rates:

http://apicciano.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2013/07/18/college-graduation-gap-narrowing-between-white-and-minority-students/

Mike Davis

Feb 13 2014 at 4:00pm

Three comments/questions:

1) The failure probabilities are surely not endogenous. Rational kids should respond to the graduation premium by…well…graduating. This is made much easier in the U.S. by the fact that there are a range of colleges which welcome less intellectually gifted students. I wonder what the data tell us on graduation rates. (Interesting corollary: should we be telling kids that mediocrity is ok? A 2.2 GPA from Directional U is works as long as it comes with a degree.)

2) Do kids really perceive the wage premium offered to graduates as a permanent thing? If not, then spending four years and lots of money getting a degree, might not make sense. Maybe they understand long run supply better than we do.

3) Why do we think kids care about expected value/utility? Optimism bias is a thing. Kids take crazy risks in every other part of their life, why don’t they take those risks when thinking about college

MingoV

Feb 13 2014 at 5:23pm

In the 1970s, a student at the 25th-percentile would not have gone to a community college and would not have been accepted by any college. Even with the dumbed-down curricula and watered-down courses of today’s colleges, these 25th-percenters have a one-in-five chance of graduating, probably with a near-worthless degree. The colleges that accept such students behave with less morality as the worst of cliched used car salesmen.

Jason

Feb 13 2014 at 7:14pm

Is the best paper you’ve read on the subject after two months of reading virtually anything really just a calibrated simulation study? Surely there are good papers that do actual empirical work? What are the next two or three best papers?

Chris

Feb 27 2014 at 10:21pm

In my case, I would have never become a great student unless every teacher, brother, and brother’s friend was telling me college was a great investment for everyone. No exaggeration.

Comments are closed.