Paul Krugman often seems more interested in the plight of the America working class than the welfare of much poorer residents of developing countries. For instance, he’s argued that lower immigration rates after the 1930s helped the American working class achieve major economic gains, and worries about unrestricted immigration.

That’s not to say that I, or most progressives, support open borders. You can see one important reason right there in the Baldizzi apartment: the photo of F.D.R. on the wall. The New Deal made America a vastly better place, yet it probably wouldn’t have been possible without the immigration restrictions that went into effect after World War I.

In a couple new pieces he almost seems to lament the fact that the bottom 80% of the global income distribution has been doing far better than most people in the top quintile.

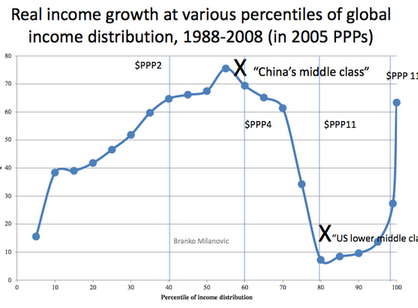

What Mr. Milanovic shows is that income growth since the fall of the Berlin Wall has been a “twin peaks” story. Incomes have, of course, soared at the top, as the world’s elite becomes ever richer. But there have also been huge gains for what we might call the global middle — largely consisting of the rising middle classes of China and India.

And let’s be clear: Income growth in emerging nations has produced huge gains in human welfare, lifting hundreds of millions of people out of desperate poverty and giving them a chance for a better life.

Now for the bad news: Between these twin peaks — the ever-richer global elite and the rising Chinese middle class — lies what we might call the valley of despond: Incomes have grown slowly, if at all, for people around the 20th percentile of the world income distribution. Who are these people? Basically, the advanced-country working classes. And although Mr. Milanovic’s data only go up through 2008, we can be sure that this group has done even worse since then, wracked by the effects of high unemployment, stagnating wages, and austerity policies.

Furthermore, the travails of workers in rich countries are, in important ways, the flip side of the gains above and below them.

In fairness, Krugman clearly welcomes the gains of the lower 80%, and it’s hard to argue with his view that it would be nice if the working class were doing better. Nor does he come right out and say that these trends are bad. My comments reflect the way he frames these issues. Start with the comment about those at the “20th percentile.” Most people would describe those people as being at the “80th to 98th percentile” or being in the top 20% (but not the top 2%.) That would make the American working class seem much more like lucky duckies. The term ’20th percentile’ sounds much more depressing. Here’s a graph in one of his blog posts, which describes the data:

I’m not trying to criticize Krugman’s views in this post; the first piece I quoted from expresses mostly reasonable concerns about the welfare of working class people. Rather I’d remind you that Krugman often scolds conservatives for being heartless, mean-spirited ideologues. But conservative economists typically claim that they believe their proposals will help the lower classes. The progressive response is, “OK, but then why do you talk so much about ideas like tax cuts for the rich?” Fair enough, but then why does Krugman focus so much on the welfare of the top quintile, and so little on the welfare of the much poorer bottom 4 quintiles?

My point is this. If you (like me) are much more concerned about the problems faced by bottom 80 percent than the top 20 percent, then don’t be intimidated by Krugman’s scolding. You hold the moral high ground.

READER COMMENTS

johnleemk

Jan 8 2015 at 10:28pm

In a recent post at openborders.info, I discuss how abolishing/reducing immigration restrictions are just an application of Krugman’s own recommendations writ large. The parallels between exclusionary immigration laws and exclusionary housing laws (that Krugman has regularly denounced for the past couple decades or so) are really striking.

Scott Sumner

Jan 8 2015 at 10:50pm

johnleemk, Good point.

Brian

Jan 9 2015 at 12:34am

Scott,

I’m not sure why you don’t want to criticize Krugman here–there’s so much deserving of criticism. Krugman seems to support anything that allows him to say “Democrats good, Republicans bad.” Consequently, many of his positions are mutually contradictory or incoherent.

The rapidly growing incomes of poor people around the world means that global inequality is shrinking–doesn’t he think that less inequality is good?

His comment about the 20th percentile when it should be the 80th is an egregious error, driven by his ideological bias.

His “valley of despond” corresponds to first-world working class people who, because they are extremely wealthy by world standards, prefer to consume their wealth by buying cheap items made overseas, thus causing the standard free-market flow of wealth from capital to labor. This effect is a straightforward result of free global trade, an approach Krugman likely supports when he’s wearing his economist’s hat.

If anything deserves lamenting, it’s that the lowest 10% of the world’s population is still not sufficiently integrated into the global economy to benefit from all this flow of wealth.

Lorenzo from Oz

Jan 9 2015 at 12:54am

But most of that gain was not from immigration, even if “sending money home” is a major source of income transfers.

My problem with open borders is twofold. One, giving the working class/lower middle class in developed countries a sense that they have no say over things that matter to them: not healthy for democracy. Second, the danger of poisoning the waters one swims in.

It is not clear to me that societies are infinitely elastic in their ability to absorb people. Trading with rich & successful countries has been a major part of the mass shift from global poverty, and if open borders lead to said societies being less rich and less successful, because it turns out societies are not infinitely elastic in their ability to absorb people, that would not be good.

My country, Australia has 23% foreign born–so is much more proportionately open than the US. But it is also based on a policy that gives folk a sense of control. So, apart from some Muslim Lebanese problems in Sydney, immigration has been managed with relatively little fuss. But we are also generally very good at “cherry picking” our migrants (the Muslim Lebanese in Sydney being a bit of a case of the exception that proves the rule). So, a good example for generous immigration, but not for open immigration.

johnleemk

Jan 9 2015 at 4:07am

I don’t know why people insist open borders = being anti-democratic or anti-national sovereignty. The point of advocating any policy change, including one to immigration policy, is to encourage the sovereigns (which in democracies are the people) of the world’s countries to change their policies. No open borders advocate that I know of advocates armed revolution and/or the overturn of democracy as a strategy for implementing open borders. Certainly that isn’t a position Bryan has ever adopted on this blog or the bloggers of openborders.info have adopted.

Perhaps the concern is just limited to the economically-marginalised feeling even more sociopolitically/socioeconomically marginalised when they see immigrants with jobs and settling in their communities. But you could make that argument against any sort of policy that happens to result in non-poor citizens getting jobs. Unemployed men must have felt pretty lousy seeing women getting jobs; unemployed whites in the US during the Jim Crow era definitely did not approve of blacks “taking their jobs”. These kinds of arguments, being based more on bigotry and prejudice than actual substance, don’t seem very legitimate. Sure, it is good to empower the working classes. But we wouldn’t want to empower the working classes by banning non-poor people from taking any jobs before every single poor person has a job and/or feels empowered. What makes immigration the exception to this rule?

Now, the concern might be that if open borders becomes the norm, people will feel that they don’t have the authority to close their borders. But you have to specify precisely what you mean by this. If immigration controls are the only way to prevent against a clear, defined threat then even most open borders advocates I’ve seen (perhaps anarchists like Bryan aside) would concede that such controls are justified. That being the case, it seems difficult to argue that open borders is an arbitrary blanket ban on implementing movement controls of any kind.

And it seems to me that a different way to specify one’s problem with open borders is that even if immigration levels of a certain amount don’t represent a specific, definable threat, the sovereigns of a country still have the authority to exclude people they don’t like — even if these people haven’t harmed them and there is no reason to expect these people to harm them. But when it comes to laws literally enforced at the point of a gun, I think the bar for policymaking ought to be set a little higher “We should enshrine these people’s set of arbitrary preferences into law.”

Obviously sovereignty implies control over and a monopoly of violence over a particular territory. But that tells us nothing about what uses of sovereign force are justified. It does not suffice to assert that using force to exclude foreigners is always inherently justifiable, even if it’s simply to enforce a particular set of arbitrary tastes, without articulating why such exclusionary force is warranted.

Sure. But the point is that there’s no evidence societies aren’t inelastic. Regardless of the immigration levels that we have been able to observe in past or present, societies seem to cope pretty well. Now, obviously countries of 90% immigrants are pretty rare so I don’t think anyone would go out on a limb to say that that’s definitely not going to present an issue. But at what point then should we draw the line? It is of course easy to say “At some arbitrarily-determined point that I choose which will make me feel safe.”

But people could say that about any sort of change. In the US context, abolishing the draft was one such major change — it was absolutely unthinkable in many of our lifetimes. Gay marriage too was quite unthinkable. You could go on and on. Either you have to believe that we ought to freeze our societies in stasis, or you have to accept that we can at least tolerate certain societal changes in the face of continuing absence of evidence that they are harmful.

My point is not that countries should refuse to dabble at all in controlling immigration. Hardly any serious non-anarchist scholar advocating open borders takes that position. My point is that the precautionary principle is not an excuse for advocating arbitrary migration controls, when in fact there is no evidence that such migration controls are essential to the maintenance of functioning societies or civilisations. The best precautionary principle-based argument is that immigration should be tolerated unless and until effects seeming to warrant arbitrary controls manifest. Until we have such evidence, opposing gradual and continued liberalisation of immigration laws is adopting a completely evidence-free position, based more on prejudice than proof.

At the end of the day, my position on such social issues very much resembles that of Richard Posner’s in the below transcript from the gay marriage case Wolf v. Walker.

Harold Cockerill

Jan 9 2015 at 5:38am

If I was going to point at something to argue about then Krugman’s statement “The New Deal made America a vastly better place,” would be it.

bill

Jan 9 2015 at 6:51am

Another way to show the data would be to show two lines: one with 1988 income levels and another with 2008 levels (might need to use log scales so that the changes in the top 1% or 5% don’t make the changes below the 5% become invisible). Here’s what this would highlight (I need to use made up numbers since I don’t know the real data). Maybe income levels at the 50%-ile rise 70% as shown – from $8,000 to $12,600. And the rise at the 85%-ile is an 8% rise as shown – from $20,000 to $21,600. When seen that way, it becomes harder to imply “I feel that every income group except the top 1% should get the same percentage increase”. Seeing the global lines “flattening” is more appealing than to see that two humps which imply that the American poor is just losing.

Lorenzo from Oz

Jan 9 2015 at 8:29am

Because pro-immigration advocates often they advocate tolerating illegal immigration. A legislatively decided policy of open borders is a somewhat different beast than effectively demanding the law be ignored, since that really does deprive folk of any say. Especially if one adds in a push to de-legitimise scepticism about immigration. In Sweden, that has gone so far as to appear to be heading towards “rigging” election outcomes.

But, even in the openly decided case, the costs fall fairly heavily on those who primarily sell their labour and potentially on a rather larger scale than the cases you are talking about.

Not being a fan of the precautionary principle, that was not the basis on which I was proceeding. Nevertheless, a certain caution seems appropriate, since the stakes are so high if it turns out that societies are not infinitely elastic in their ability to absorb folk and continue to function in a roughly preferred fashion.

On the evidence of Australia, the US could afford a much more generous immigration policy than the one it has. I am just leery about anything that approaches open slather.

Lorenzo from Oz

Jan 9 2015 at 8:40am

There is also a bit of an issue in Europe of problematic local spaces.

Jeff

Jan 9 2015 at 9:02am

@johnleemk,

The tradition argument doesn’t work for immigration. Before the early 20’th century, the US had no immigration restrictions at all, so you could just as easily say that open borders are the “traditional” position.

Lorenzo, I think in the US at least, most people who vigorously oppose illegal immigration also want to restrict legal immigration to what are, historically, pretty low levels. After all, we could easily get rid of all illegal immigration by repealing the laws that make it illegal for free men to live where they want to.

Left liberals today favor more legal immigration from Latin America because they expect that those immigrants will vote Democratic. That’s all they really care about. Some of the more intelligent among them, like Krugman, realize that you can’t sustain a welfare state if huge numbers of immigrants can come in and live on the dole. There is also research showing that the more ethnically diverse a society is, the less support there is for a large welfare state, as many people don’t like supporting people who don’t look and talk like they do.

Scott Sumner

Jan 9 2015 at 12:47pm

Brian, That’s sort of my gut reaction. But Krugman often tends to be a bit vague on certain points, and if I criticize what he SEEMS to be saying, his supporters will comment that I have misrepresented his views. So I’m trying to leave it up to readers (like yourself) to draw their own conclusions.

I like to give people the benefit of the doubt, and assume the 20 percentile figure was a simple mistake.

Lorenzo, Good points.

Johnleemk, Good points.

Harold, Good point.

Lorenzo from Oz

Jan 9 2015 at 7:47pm

Jeff, any references? It is what I would expect, and is relatively clear from just eye-balling the data, but some scholarly back-up would be good.

Jeff

Jan 9 2015 at 8:30pm

Lorenzo,

According to this survey:

idei.fr/doc/by/vanderstraeten/joes.pdf

the evidence is there but it is not very strong. I recall seeing stronger results referred to a few years ago, but this is not my field and I can’t claim any expertise in it. The great thing about a survey paper, of course, is that it has lots of references you can pursue if you’re really interested.

Steve J

Jan 10 2015 at 1:12pm

I’m trying to figure out your point here. Of course Krugman cares (or at least pretends to care) more about US workers than foreign workers. It is the US workers who read his work and fund his paycheck. This data fits Krugman’s narrative perfectly. Everyone other than the first world middle class is seeing growth – where’s mine?

Comments are closed.