This will probably be my most important post of the year, but I predict that almost no one will pay any attention.

Macroeconomics is a deeply flawed field, because it is extremely hard to do controlled experiments. Ideally, you’d like governments to do wild and crazy things, like a sudden 30% cut in the money supply—just to see what happens. But after the Great Depression, governments have little stomach for these sorts of experiments. Nonetheless, they do happen on rare occasions.

June 2016 was one of those occasions. The British public voted for Brexit, creating enormous uncertainty about the future course of the UK economy. This was widely treated as the biggest shock to hit the UK since the Suez crisis, if not WWII. There was great uncertainty about how it would play out. Would City banks still have (passport) access to the Continent? Would it be a soft Brexit (with continued free trade) or a hard Brexit? The consensus among economists was that this uncertainty shock would lead to a dramatic slowdown in growth.

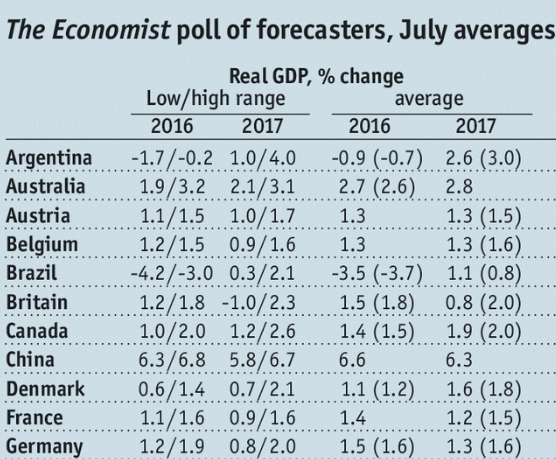

The Economist magazine reports the consensus growth forecast for 2017. In early July, they reported a sudden drop from 2.0% in June to 0.8% in July:

But even that understates the shock, as not all forecasters had revised their predictions. By the August issue the forecast for 2017 had dropped to 0.5%, where it remained in September. That’s actually consistent with a couple negative quarters, and hence a mild recession. For instance, the US experienced a mild recession in 2001, despite 1.0% RGDP growth (calendar 2001 over calendar 2000.) Since September, however, the Economist’s consensus forecast has been steadily creeping higher.

Then a few days ago the UK came out with shocking 4th quarter RGDP data, showing a 0.6% increase (an annual rate of 2.4%.) The second such increase in a row. Now the Bank of England has revised its 2017 growth forecast back up to 2.0%:

Alongside news that the BoE had kept its key interest rate at a record-low, the British central bank lifted its 2017 economic growth prediction to 2.0 percent from a 1.4-percent forecast just three months ago.

It now appears that Brexit (i.e. the vote, not the policy) had absolutely no impact on RGDP growth. Sound familiar? Recall when the 2013 austerity was widely expected to produce a sharply showdown, and growth actually sped up. (Unlike Brexit vote, the austerity began January 1, 2013, so I use Q4 over Q4 figures.)

In the field of macroeconomics it is very unusual to see an almost perfect test of the “uncertainty theory of business cycles”. I certainly never expected to see such a nice natural experiment. Now that it is over, we can remove one suspect from the list of possible causes of business cycles, which include monetary shocks (falling NGDP) and real shocks (things that cause RGDP to fall even if NGDP growth is kept stable by monetary policy.)

My own view was more optimistic than the consensus, but even my view turned out to be wrong. I thought unemployment might rise by about 0.5%, whereas now it looks like unemployment will not rise at all.

As of today I am even more a market monetarist than I was last year. I’m even more convinced that NGDP shocks are what cause employment fluctuations. That’s not to say that real shocks don’t matter. I still think a complete shutdown of oil from Opec or a $20 minimum wage would cause a recession, even with steady NGDP growth. But I don’t expect to see either of those shocks.

Back in March 2011, we learned that even a devastating earthquake/tsunami, which led to the complete shutdown of the extremely important Japanese nuclear power industry, would not impact the Japanese unemployment rate. So we can also rule out natural disasters as a cause of business cycles for big diversified economies. (On the other hand a small economy can be tipped into recession by a natural disaster, as we saw a few years ago in Haiti.)

And of course we now know that a sudden $500 billion cut in the budget deficit will get offset by Fed stimulus, even at the zero bound.

I started off with the pessimistic prediction that this natural experiment would not matter. I believe that economists who favor uncertainty theories of the business cycle will simply wave away this near-perfect experiment. They might argue there actually wasn’t all that much uncertainty. But that would merely prove uncertainty theories to be useless for a different reason—because we are unable to ascertain in real time what uncertainty looks like. Or they will argue that some other mysterious factor prevented their theory from working, as Keynesians did after the failed 2013 austerity predictions.

We don’t live in a Bayesian world where macroeconomists update their priors after failed experiments; we live in an ideological world. But the minority of us who do have open minds learned a lot in 2016–and we should celebrate that success even if we were wrong (as I was somewhat wrong.)

PS. The effect of Brexit itself (expected in 2019) is a completely different issue. I do expect Brexit to reduce UK RGDP growth, but only modestly. I remain opposed to Brexit. But I’ve changed my priors on uncertainty theories from “a negative real shock but less important than the consensus believes” to “not a factor at all.” Maybe I’ll later change my mind on Brexit itself.

PPS. If you are puzzled about how an economy can grow in a recession year, imagine the following thought experiment. Suppose an economy grows at a two percent rate all throughout the year before a recession. It ends the year 2% above the previous year. Now let it decline a couple tenths of percent for two quarters in a row, and then level off. For the year as a whole, RGDP is actually up about 0.8% over the average of the previous year, even though the year saw slightly negative growth on a Q4 to Q4 basis.

PPPS. Those reluctant to change their minds should reflect on the fact that the “losers” of intellectual debates are actually the winners. The “losers” learn something, becoming smarter. The winners learn nothing, and simply become even more arrogant jerks.

READER COMMENTS

Steve Fritzinger

Feb 2 2017 at 10:45am

“…economists who favor uncertainty theories of the business cycle will simply wave away this near-perfect experiment.”

Do you make a distinction between the effects of real shocks caused by policy changes and uncertainty?

You made a strong case in The Midas Paradox that gold and wage shocks prolonged the Depression by years. I read that as consistent with Higgs’ regime uncertainty.

Is the difference that in the shock model, businesses are constantly trying to react to the shocks but in the uncertainty model they just hunker down?

HM

Feb 2 2017 at 11:05am

I think you might be a bit too pessimistic. It is probably true that some people with strong priors for uncertainty shocks will not be fully converted by this natural experiment.

However, macroeconomics is also driven by people on the fence who choose to go into different areas. My impression is that Brexit has had a major impact on the credence of uncertainty theories for these non-committed economists.

I’ve heard your argument repeated by multiple macroeconomists over drinks, and I’ve pointed to your early post as a daring and correct prediction. I’m willing to bet that five years down the road, the share of uncertainty shocks paper will have gone down, and people will point to the Brexit-episode as an important cause.

Maurizio

Feb 2 2017 at 11:17am

Thank you for the post. That real shocks don’t matter for business cycles is a very important claim, I think.

I get that Brexit is not that bad for the British. Ok, but what about Italexit for Italians?

pyroseed13

Feb 2 2017 at 11:30am

I’m a bit confused by this post. What good reason is there to still be opposed to Brexit even though all of these supposedly disastrous scenarios have yet to unfold? And is this really evidence that real shocks don’t matter for the business cycle, or is it maybe evidence that Brexit wasn’t much of a negative shock at all?

Todd Kreider

Feb 2 2017 at 11:32am

We little people are paying attention, Scott!

1)

I don’t understand why there was a consensus among economists (if that was the case) that Bretix would cause a “dramatic slow down in growth.” Why would that have happened? My prediction (and written at MR) then was that there would be little longer-term effect. I didn’t think of it at in these terms at that time, but I didn’t consider a “hard Brexit” likely at all but either a soft Brexit or a feather-light Brexit, more likely the latter.

2)

The consensus of Economists seriously forgot about the 2008/2009 financial crisis where a number of well known economists were even warning of The Great Depression II?

3) The odds of an OPEC shutdown are around 0.00% +/- 0%

As I argued in 2011, Japan’s nuclear industry isn’t “extremely important” (but nice to have around). While it was a poor decision for the government to shut down all nuclear power plants, they only supplied about 10% of Japan’s total energy and could be fairly quickly replaced by fossil fuels.

AntiSchiff

Feb 2 2017 at 11:39am

Dr. Sumner,

Another problem with macroeconomics is there often isn’t much data, controlled or otherwise, to build our test models with. I’m finding this as a problem myself as I seek to go beyond simple event testing to producing time series predictions, for example.

Based on the initial FTSE 250 reaction to the Brexit vote, I expected a .85% hit to NGDP, and a rise in unemployment of .55%. Obviously that didn’t happen, but then that could be because the BOE performed better than expected.

I am surpised though by the RGDP figure which I assumed would take a greater hit.

Scott Sumner

Feb 2 2017 at 1:28pm

Steve, No, the gold shocks worked through lower NGDP, and the wage regulation shocks worked through higher hourly wages. Neither worked through uncertainty. They worked through both sides of the musical chairs model:

W/NGDP is correlated with the unemployment rate

HM, That’s plausible. I hope you are right. (Hence the title of my post, a reference to the famous line “science makes progress, one funeral at a time”.)

Maurizio, I think that Brexit is bad for the British. What doesn’t seem to be bad is Brexit uncertainty. I think it would be a mistake for Italy to leave the EU, and don’t expect it to happen. (It might leave the euro, although even that is unlikely.)

Todd, They expected the uncertainty created by Brexit to lead to a sharp fall in investment, which would reduce GDP growth.

You said:

“While it was a poor decision for the government to shut down all nuclear power plants, they only supplied about 10% of Japan’s total energy and could be fairly quickly replaced by fossil fuels.”

That’s a bit misleading. The plants supplied 30% of Japan’s electricity. That’s a lot. The disaster also disrupted supply lines in many important manufacturing industries. I recall reading predictions of a Japanese recession.

Perhaps when they said the biggest shock since Suez, they meant the biggest real shock.

Antischiff, Those are almost exactly my views.

Anand

Feb 2 2017 at 2:27pm

[Comment removed. Please consult our comment policies and check your email for explanation.–Econlib Ed.]

Andrew_FL

Feb 2 2017 at 2:59pm

@Steve Fritzinger

Higgs nowhere claimed regime uncertainty as a business cycle theory. An important distinction to make here.

Remember that Higgs is not trying to explain the Great Contraction, he is trying to explain why the economic recovery was lackluster to non existent for a decade or so.

Yaakov Schatz

Feb 2 2017 at 3:13pm

Scott, I am a non-economist reading about economics for maybe 20 years now. Never has macro-economics been made so clear to me as in your posts. Many thanks.

Scott Sumner

Feb 2 2017 at 3:19pm

Thanks Yaakov.

Britonomist

Feb 2 2017 at 4:14pm

“PS. The effect of Brexit itself (expected in 2019) is a completely different issue. I do expect Brexit to reduce UK RGDP growth, but only modestly.”

Then you should revise your wording earlier where you said:

“now appears that Brexit had absolutely no impact on RGDP growth”

When you actually meant just the referendum.

Also, still not really a controlled experiment. There’s still no counter-factual, we still don’t know if growth would be much higher now were it not for the vote.

I’m also still unsatisfied how you can square this with theory. Expectations matter, markets work with long and variable leads. If something bad happens like total loss of passporting, this affects the city badly – it’s reasonable to assume things like this affect current investment & employment/expansion decisions.

Britonomist

Feb 2 2017 at 4:35pm

Also, the BoE did some rather drastic actions, including additional QE, immediately after the vote, just to maintain a mediocre at best growth rate for the year. The fact that the BoE had to do this rather suggests to me that the referendum did have an effect, but was subject to monetary offset.

bill

Feb 2 2017 at 4:43pm

I like this post. And I like changing my mind (or having it changed).

Comment: I think the uncertainty from things like Brexit do make it harder for central banks to keep NGDP on track. The BOE succeeded, but that wasn’t preordained. But with this result in hand, we can truthfully assert that the next time a central bank allows a recession after some uncertainty shock that it was their fault. And they can say, “true, but it’s just harder when uncertainty increases so much”. Like Lehman’s failure didn’t cause the financial crisis, but it did make it harder for the Fed to keep things on track. And why the Fed thought the correct response to such a shock was to do nothing at that next meeting is truly incredible.

Todd Kreider

Feb 2 2017 at 5:01pm

Scott, you wrote:

But investors likely quickly knew that 1) Brexit might not go into effect and 2) there are strong political forces to keep trade and investment quite open through separate negotiations if necessary. These expectations must have been a large factor in assuming business would be *mostly* as usual and that a radical Brexit would be very unlikely.

Both stating nuclear supplied 10% of Japan’s energy and 25 to 30% of electricity is correct. The 10% total figure gives a better picture since relative to total GDP.

Japan’s real growth was 4% in 2010, still recovering from the late 2008 financial crisis hit – a real shock. Growth was slow the quarter before the 3/11 earthquake but dropped to 0% for the next two months before 3% annual for two months after that. But since nuclear power can be fairly quickly substituted with fossil fuels, it isn’t known to what extent the bad shut-down-the-nukes policy had on the economy relative to other factors. Unlike the 1995 Kobe earthquake that hit a city, the 9/11 tsunami significantly damaged a larger area including Sendai, pop. 1 million.

James Alexander

Feb 2 2017 at 6:06pm

Britonomist is right though I don’t recall him recognising the immediate monetary offset at the time. Scott, you should have done. Some Market Monetarists (ahem) spotted it immediately and made the correct prediction.

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2016/06/30/carney-helps-clear-a-mess-he-partly-made/

James Alexander

Feb 2 2017 at 6:11pm

And this more considered piece in August, but still just 8 weeks after the referendum, when confidence surveys were still very worrying.

http://ngdp-advisers.com/2016/09/08/boes-new-monetary-policy-tool-toleration-target-projected-inflation/

James

Feb 2 2017 at 7:51pm

Scott,

What could happen in the world to make you less of a market monetarist?

Thaomas

Feb 2 2017 at 10:33pm

That increased uncertainty, say about Brexit, reduces demand for consumption goods is a ceteris paribus prediction, about the sign of a variable in a model. Without knowing what else was in the model being assumed unchanged or changing in certain ways, I do not see how roughly unchanged real growth in the months since Brexit vote bears on the estimate of the uncertainty parameter.

For example, maybe folks were expecting that Brexit vote would lead to an increased demand for foreign exchange but that BOE would try to prevent a depreciation of the exchange rate by tightening monetary policy leading to a recession. But if BOE did not behave as the model predicted THAT is the erroneous parameter, not the uncertainty parameter. Ditto if there was a bad estimate of the how consumers form their expectations about exchange rate movements and how that would feed into price movements.

All we can know is that something was wrong with the model, but not what without it.

James Alexander

Feb 3 2017 at 1:27am

Thaomas

Good comment. Pre-Brexit the BoE made it very, very clear what they would do. Ease. See my link above.

As in 2008, 99% of economists even Scott Sumner, forgot what basic macroeconomics tells them is the effect of a devaluation. Blinded by ideological attachment to the idea of the EU, they missed what would come. A textbook case of monetary offset.

It’s a shame that our modern founder of monetary offset hasn’t yet written the textbook on it. Now he’s blinded by TDS instead.

Scott Sumner

Feb 3 2017 at 10:34am

Britonomist, Thanks I fixed the wording.

As far as monetary offset, I judge policy stances by NGDP growth, not QE or interest rates. Thus I see monetary policy as being stable. The natural rate of interest fell, but I don’t view that as monetary stimulus.

Bill, Good point.

Todd, But that could be said about any “uncertainty shock”. If economists can’t identify uncertainty shocks, then what use are they?

And I don’t agree that the UK is likely to have free trade with the EU. I think that is unlikely. I expect a hard Brexit.

The forex markets are also quite pessimistic, look at the value of the pound.

You said:

“The 10% total figure gives a better picture since relative to total GDP.”

We will have to agree to disagree on that point. Suppose Japan had lost 100% of electric power capability? Would you describe it in terms of total energy? Obviously not.

In any case, none of this has any bearing on the claim I made in the post, unless you can find a bigger natural disaster.

James Alexander, You missed the point. This is not about monetary offset, this is about real shocks. Not all shocks are nominal.

I did expect some monetary offset, although I wasn’t certain how much.

James, If W/NGDP becomes much less correlated with the unemployment rate then I will become less of a MM.

Or if market forecasts of NGDP growth became much inferior to Fed forecasts, that would make me less of a MM.

Thaomas, Monetary offset does not save the model. The uncertainty model works through real shocks, or else it’s just a part of a much broader monetary model of business cycles.

James Alexander, You said:

“As in 2008, 99% of economists even Scott Sumner, forgot what basic macroeconomics tells them is the effect of a devaluation. Blinded by ideological attachment to the idea of the EU, they missed what would come. A textbook case of monetary offset.”

I don’t think you understand monetary offset, at least if you think 2008 was a good example. In fact, in 2008 monetary offset did not occur.

I’m not quite sure what you mean by “the textbook” on monetary offset. Textbooks are not typically written on narrow topics, but I’ve certainly written more on monetary offset than anyone else.

And again, if you think monetary offset was the issue here, then you simply do not understand the concept. I encourage you to go back and read my earlier posts on the topic; it applies to real shocks, not nominal shocks. Macroeconomic theory does not claim that monetary offset applies to real shocks, so you are simply wrong.

In addition, I assure you that I am not “blinded” by my attachment to the EU, I’ve been extremely critical of EU policies over the past 8 years.

Unless the pro-Brexit crowd can come up with a plausible explanation for the deep depreciation in the pound (which they have not done) then their claims of prescience will ring hollow. I doubt they even predicted it.

James Alexander

Feb 3 2017 at 11:22am

OK, my comments got posted in a funny order and appeared a bit confused.

With regard to 2008 I only meant to say that 99% economists missed tight money around the Lehman moment.

The Brexit vote was a real shock and was offset by the very clearly signalled pre-vote stance of the BoE to allow the GBP to fall, and then post-Brexit kicking it down further by changing the IT to allow temporary overshoots, and more QE – for which they criticised by many hawks. Textbook monetary offset.

99% of economists were blinded by the potential disaster of Brexit so could not see how this monetary easing as evidenced and implemented by the devaluation would boost an AD shocked down by the vote. I really don’t know how you can’t see it given you have so often written about how a devaluation boosts domestic demand (see Japan).

Todd Kreider

Feb 3 2017 at 5:52pm

Scott,

When the 1995 Kobe earthquake killed around 6,000 people in Japan, nuclear power was not an issue, yet the economy that had started to recover from the asset bubble experienced little growth for two quarters before solid growth until the 1997 Asian financial crisis. I simply disagreed with your adjective writing that the nuclear industry was “extremely important”. That is Japan grew in its usual fitful way as the plants came off line, hit another recession for half a year (I didn’t understand your reasoning that that didn’t count as a recession when you seemed to put all or almost all weight on the unemployment rate a couple of years ago.)

With respect to Brexit, first, I doubted absolute free trade but thought tariffs would not be significant and that any small ones would be reduced over time. We’ll see.

Tyler Cowen posted a link to his Sept Bloomberg article where he wrote:

” formally a recession is a sequence of two or more quarters with shrinking gross national product. Most of the losses from Brexit will be felt more slowly, though they probably will be worse than a mere recession.”

That is not a formal definition of a recession but a journalist’s definition as unemployment and inflation to a lesser degree are considered as well.

But Cowen is calculating predicted “costs” by just looking at the change in currency.

“This [just looking at currency change] isn’t any kind of formal international trade model, with a full set of measurements and moving variables. It’s just a simple way of showing that the costs of Brexit can be high without a recession.”

This is why the method of his estimation should be avoided and wonder why PhD economists do this.

Todd Kreider

Feb 3 2017 at 6:46pm

I forgot this:

Scott: “The forex markets are also quite pessimistic, look at the value of the pound.”

The exchange rate doesn’t measure pessimism. One thing that does is the stock market.

The FTSE 100 rose from 6200 to 6700 by July 26th. That seems like optimism to me, as does the rise to 7000 where it sits today.

The FTSE 250 dropped sharply after the referendum passed but has fully recovered by July 26th. It has increased from 16,800 pre June referendum to 17,400 today. I’m not seeing the pessimism.

Ben

Feb 4 2017 at 4:47am

Great post. Although if Brexit does turn out to have little impact on RGDP (which is entirely impossible because the BoE seems to target NGDP far more than inflation as we see after rising inflation forecasts and the fact that exports to the EU as a percentage of GDP of the UK economy is only about 2%) what would the affect be on the economics field?

The forecasts and predictions of Brexit were perhaps the most negative and most severe of any political event in decades. If they are all completely wrong and the UK continues to prosper (it was the fastest growing economy in the G7 in 2016, even if it slows down marginally, many EU countries could still look to it as an example) that could threaten the entire creditability of the institutions that made them and, of course, the EU itself.

So you’ll have more anti-establishment parties blaming the EU as if they’re problem when it’s clearly arachiec labor laws, excessive government regulation, government ownership and complicated and high taxes. Which the UK has comparatively very little of.

jbsay

Feb 4 2017 at 9:41pm

[Comment removed pending confirmation of email address. Email the webmaster@econlib.org to request restoring this comment. A valid email address is required to post comments on EconLog and EconTalk.–Econlib Ed.]

Scott Sumner

Feb 5 2017 at 3:19pm

Britonomist, I’ve already responded to that point.

James, It can’t be textbook monetary offset, when monetary offset applies to nominal shocks, not real shocks.

Todd, There is a sense in which you are right about the nuclear industry not being “extremely important”. It obviously was not important enough to cause a recession.

My point is that it looks pretty important in terms of share of electricity produced. And of course there was lots of other damage as well. If even the 2011 disaster did not cause a rise in Japanese unemployment, and only a very small effect on GDP, I think it’s fair to say that no plausible natural disaster could ever cause a US recession. (Yes, an implausible one like a massive asteroid might, but I’m talking about disasters of the sort we see at least once in a millennium.

A fall in the pound is not always a sign of problems, but in this case I think it was. If it fell due to easy money, that would be different.

Ben, Yes, there is a risk it will help the populists.

James Alexander

Feb 5 2017 at 3:57pm

I clearly don’t follow. The 2013 US fiscal consolidation was what? Real? Monetary? Nominal?

Monetary policy offset it. I know that.

James Alexander

Feb 5 2017 at 4:03pm

With regard to the fall in the pound you must go back and study what Carney said and did – both before the referendum and in the immediate aftermath. He was very clear. The market expected easing and got it, in fact even more than expected.

Michael

Feb 19 2017 at 4:28am

James Alexander (3:57pm), 2013 austerity was a positive real shock (or do you think government is better than you at spending your money?)

The issue was whether it would also cause a negative nominal shock, which would lead to less growth (or even a recession) in the short term.

Turns out we can concentrate on the real effects in the future (if we have a central bank that knows what it’s doing), as the FED was quite capable of offsetting whatever nominal effects there were (in spite of all the wailing about zero lower bounds). That’s basically the MM position

Comments are closed.