A new NBER paper by Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo finds that “deployment of robots reduces employment and wages, but they caution that it is difficult to measure net labor market effects.”

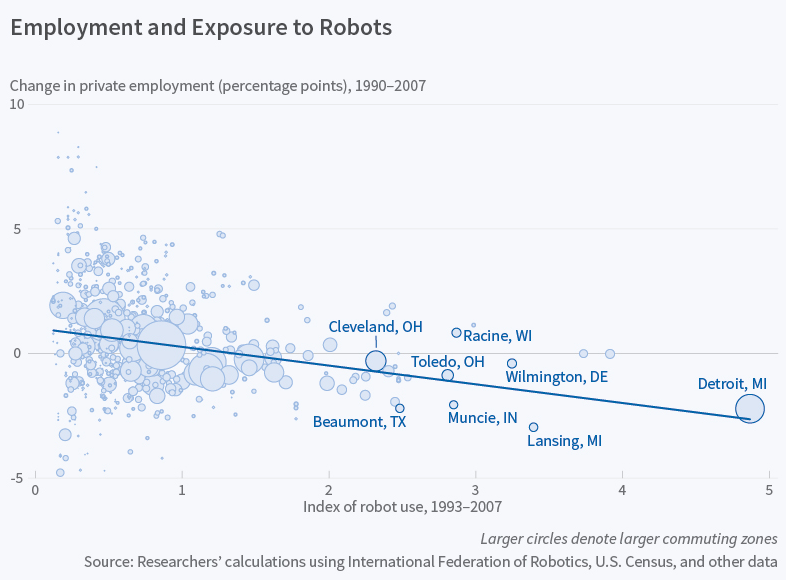

Here is a graph that summarizes their results:

Notice that cities with auto factories such as Detroit and Lansing have above average robot adoption and below average employment growth (actually negative.)

This study reminded me of the 2016 Autor, Dorn and Hanson study of the impact of Chinese trade on local labor markets. Even the time period was the same (1990-2007). As with robots, automation reduces employment in local markets, but this does not tell us much of anything about the effect on aggregate employment. Workers losing jobs in Detroit might migrate to Texas, where jobs are plentiful.

Do we have any evidence of the effect of trade and automation on total employment? Let’s look at the unemployment rate from 1990 to 2007 (both were peak years of the business cycle.)

The unemployment rate fell slightly during this 17-year period, and thus provides no evidence that either trade or automation negatively impacted employment. However the unemployment rate is only one indicator, and many people prefer the employment to population (above age 16) ratio:

As you can see the employment ratio was about the same in 2007 as in 1990, and hence the aggregate data shows no evidence that either trade or automation reduced employment during the period studied by Autor, Card and Hanson, as well as Acemoglu and Restrepo.

Of course that doesn’t mean these factors have not had a negative effect on overall employment, just that doing so would require a very sophisticated study. Unfortunately, the science of economics has not yet advanced to the point where that sort of study is feasible. And thus we are forced to admit that we simply don’t know if there is any effect on overall employment.

But I do think that we know that trade and automation raise real GDP.

READER COMMENTS

Kevin Erdmann

May 17 2017 at 12:04pm

If only Detroit could have ignored the siren song of the robots. Think of where they could be today.

Bahrum Lamehdasht

May 17 2017 at 12:57pm

If we keep increasing our use of machines in the production process then we will inevitably reach a point at which we have machines creating machines … the dreaded Terminator syndrome!

Adam

May 17 2017 at 1:12pm

Interesting points. Spatial analysis too easily confounds multiple effects.

Net out migration’s been going on in Michigan for decades. Workers migrate out to high opportunity areas.

Who’s migrating into MI? Some workers, but also those who seek a low cost of living to offset low wages and part-time work?

Hazel Meade

May 17 2017 at 1:24pm

I would hope so. Robots are supposed to be labor saving devices, are they not?

Mark Bahner

May 17 2017 at 5:39pm

A few comments (all saying basically the same thing :-)):

1) “Past performance is not an indication of future results.”

2) Suppose robots/computers were lilies in a pond. When the pond gets all filled with lilies, the robots/computers have all the jobs. The lilies double in number about every year. Right now, hundreds of years since the start of the industrial revolution, the lilies cover only 1% of the pond (i.e. humans have 99% of the jobs). At a doubling rate of once a year, when is the pond 100% full of lilies (i.e. when do the robots/computers have all the jobs)? The answer is, of course, about 6.6 years…it’s 6.6 doublings to go from 1% to 100%.

3) To convert to a real world situation, by my calculation all of the computers in the world today have a brainpower of about 10 million people. That’s less than 1/700th of the human population of over 7 billion.

The question is, what will be the power of computers/robots in 2037…20 years from now? By my calculation (seeing further, standing on the shoulders of giants! :-)), the answer is 1 TRILLION people. So in 20 years, the computing power of computers/robots will have gone from less than 1/700th of the human population, to more than 100 times the human population.

Recalculating world computer power

The economics profession–as well as the rest of the world–needs to understand how amazingly fast things can change when, like the total computing power of the earth’s computers, they double essentially every year. And yet these changes are barely noticeable when they’re at the 1% level.

Andrew_FL

May 17 2017 at 7:55pm

Drop Detroit out of the graph and it’s much harder to see any relationship at all.

Andrew_FL

May 17 2017 at 8:01pm

While we’re at it, if a place becomes unpleasant for people to live, say, because of a high crime rate, such that there’s significant out migration, but it remains a good place to do business, employers will have to substitute machines in lieu of employees-in other words, lower employment-actually lower population-can cause automation, rather than the other way ’round. And Detroit hit peak population in the 50s.

Thaomas

May 18 2017 at 6:38am

I agree that it is crucial to think about the aggregate effects of trade/automation/whatever rather than just local effects. But…

1) Local micro effects are important in thinking about adjustment costs and therefore for polices that might speed up adjustment or reduce the pain of adjustment and possible trade offs between these policies and perhaps heading off political backlash against trade/automation/whatever.

2) Employment or unemployment per se may not be the best way to measure these aggregate effects. If, stereotypically, the displaced high income factory worker is displaced and finds work at McDonalds at a much lower wage, this does not show up in the aggregate employment numbers.

Thaomas

May 18 2017 at 12:23pm

It is distressing to see both Hazel Meade (or was that a joke) and Mark Bahner reason from a fixed number of Jobs presumption.

Mark Bahner

May 18 2017 at 5:14pm

What I reasoned from was a knowledge of the rapidity of change associated with artificial intelligence. For example, I’m almost certain that autonomous (computer-driven) delivery vehicles will devastate the brick-and-mortar retail industry. I’m thinking that 90%+ of brick-and-mortar stores of Walmart, Costco, Target, Kroger, Publix, Rite-Aid, Walgreens, Lowes, Home-Depot, etc. will be shuttered or re-purposed (as warehouses…most likely staffed by robots) in the next 10-30 years.

Where will all the people who work in those stores right now go? I’m talking cashiers, sales people, janitorial staff, etc. You can’t say, “They’ll go to some other chain.” I’m talking about essentially all the brick and mortar stores of all the chains of every type of store.

That’s a tremendous number of people, many of whom probably don’t have much experience or ability beyond what they’re currently doing. I think it’s very, very bad for anyone to just say, “Oh, they’ll find something. It’s always worked out in the past.”

What are some examples of jobs those literally tens of millions of people can switch to as the retail industry is turned on it’s head inside a decade or two?

Hazel Meade

May 18 2017 at 6:10pm

Mark, I think the problem is that the workers whose jobs are automated don’t stand to directly benefit from the labor-saving aspect of the automation.

What if the employer split the gains 50-50 (or some other ratio) with employees they laid off as the result of automation? The employee can move on and find a new job at a lower salary and/or additional leisure, but will be compensated with some additional income earned from the profits derived from automation.

One could offer stock options as part of a termination package, for example.

Mark Bahner

May 18 2017 at 7:37pm

Hi Hazel,

You write, “What if the employer split the gains 50-50 (or some other ratio) with employees they laid off as the result of automation?”

In the scenario I outline, everyone loses. Well, not everyone…customers gain. But all these brick and mortar stores lose. The only winners are people like Amazon who already specialize in online sales, and potentially some brick-and-mortar chains that can switch to online in a way that can compete with Amazon and the folks already online. Plus, those brick-and-mortar chains need to figure out some way to profitably sell their brick-and-mortar assets in what should be a pennies-on-the-dollar buyers market. So if the whole company is losing due to automation, there isn’t a lot of money to share.

“One could offer stock options as part of a termination package, for example.”

Stock options in Enron as part of the termination package! 🙂 Seriously…all these brick-and-mortar stores are going to be scrambling. I think many of them will end up the way I think Sears is going to end up within a couple years at best.

P.S. I don’t want to paint all gloom and doom. In…40 years at most…no one is going to have a job. But that will be because no one will need a job to survive, because the machines will be able to do everything. So everyone will be able to be “retired” in comfortable circumstances. But getting to that endpoint is going to be a very bumpy ride.

Kevin Erdmann

May 18 2017 at 9:53pm

Mark Bahner:

“In…40 years at most…no one is going to have a job. But that will be because no one will need a job to survive, because the machines will be able to do everything. So everyone will be able to be “retired” in comfortable circumstances. But getting to that endpoint is going to be a very bumpy ride.”

This already happened. A century ago. We live in that world now. Oddly, one could say both that (1) it was a bumpy ride and (2) apparently nobody noticed.

Andrew_FL

May 19 2017 at 12:41am

Area Monetarist denies scarcity

Kevin Erdmann

May 19 2017 at 2:22am

Andrew_FL, quite the contrary. I’m pointing out its permanence.

Mark Bahner

May 19 2017 at 5:52pm

Kevin…is that like the codename for Klaatu? 😉

I know you folks on the other planets have robots for police, diamonds for pocket change, and other advanced stuff, but here on Earth we’re a bit behind.

Like I wrote, in…40 years?…robots/computers will be able to do everything. As soon as I see your buddy Gort out catching criminals–or vaporizing them with his Cyclops beam–I’ll agree that our planet has reached omnipotent computer/robot technology. Right now, here on earth, machines can’t do much.

Kevin Erdmann

May 21 2017 at 2:55pm

Mark, there was a time when 80 or 90% of labor was in agriculture. Now it’s low single digits. I don’t think you are even forecasting that much of a transformation. Go explain to your great great great great grandpa why it’s ok to automate ag because those workers will become systems engineers and yoga instructors. The future jobs that people will do will make as much sense to you as turning pinups into 1s and 0s which fly through the sky to little windows in teen boys’ pockets would make to him. All the jobs in his world are gone. And we have maagic windows in our pockets that suck up flying 1s and 0s. The future is much larger than our imaginations.

Mark Bahner

May 24 2017 at 5:45pm

Yes, in 1790, 90 percent of labor was in agriculture. In 2000,210 years later, it was 2.6 percent.

I’m talking about 90 percent of *all* occupations belonging to humans and then less than 2.6 percent belonging to humans less than 40 years later.

See my response above. Don’t you think that the same type of transformation that happened over 210 years happening in less than 40 years is pretty mind-blowingly disruptive?

Hayden Alexander Wade

May 25 2017 at 3:12am

While robots are currently reducing employment rates, I believe it is because robots being used for work is not yet a regular thing. As technology progresses in the next few years, and robots being used becomes a more common thing, employment and jobs will start rising again to assimilate for maintaining and creating these robots that do all the work.

Comments are closed.