In previous comment sections, I’ve seen a lot of confusion over the concept of “monopsony power”, which means the buyer can influence the price of what they buy. It is the buyer side equivalent of sellers having “monopoly power”.

Many people seem to assume that only monopolies have monopoly power. Not so, most firms do. If your firm can raise prices by one penny without seeing sales drop to zero, then you have monopoly power. And if you can reduce wages by one penny per hour without losing all your employees, then you have monopsony power in the labor market.

That’s not to say perfect competition is not a useful model, it’s is a good approximation of reality in some contexts. But it’s becoming increasing clear that monopsony power is more than a minor characteristic of the labor market, it gets to the heart of the current issue of labor shortages.

Rick Newman of Yahoo.com did what I’ve been calling on reporters to do, in depth interviewing to see what a “labor shortage” involves. He decided to interview a small manufacturing firm in Indiana, to get a sense of how there could be a shortage of labor. I’d encourage you to read the entire piece, as it beautifully describes what a labor shortage feels like from an employer’s perspective, when they have monopsony power:

And you’ve had a hard time finding workers lately?

The unemployment rate in my area is about 2%. [Indiana’s unemployment rate is 3.6%, lower than the national rate, now at 4.3%.] We’ve struggled to hire office staff, entry-level, skilled and highly skilled employees. Almost every business owner around here is struggling to find help. Help wanted signs are posted throughout the community. We have three key positions open right now, which amounts to almost 10% of our workforce.

So this is not typical of America, it’s a really, really tight labor market.

Are you paying more these days?

We have been paying more. Starting wages have gone up 20% to 30% in the last three years. At the entry-level, we’ve had to raise starting pay from $11 per hour to over $13 per hour. That’s for somebody with little to no applicable skills, in need of significant training. For skilled workers, pay has gone from $14 or $15 to $18 to $20, and highly skilled, even higher.

That’s also atypical; at the national level wages are rising less rapidly.

Our readers raise a reasonable question: Why don’t you pay even more to get the people you need?

We will as long as it makes sense. If there was a direct correlation between the amount you pay somebody and the amount you’re able to get as an output, including loyalty and dedication, simply paying more would be a no brainer, but business isn’t just binary. Some businesses have price inelasticity, high fixed expenses and tight margins, and raising wages too quickly could greatly affect the company’s ability to turn a profit. You can’t just say, I’m going to raise labor costs without considering all the other variables that impact the business. . . .

What kind of workers are hard to find?

Right now in our area, all kinds, at all wages. We have struggled to find people from the front to the back of the business. Office workers, service workers, trades people, general labor, engineers, sales people. . . .

Getting people to show up is as important as getting people with skills. If you’re absent, chronically missing work or always late, you are not protecting your job or concerned with your future at the company. It’s hard to want to help those people. When the unemployment rate is under 2%, the people who are responsible, really good, valuable, are taken, so you have to figure out how to attract good workers from other companies. Many business owners and HR folks I have talked to feel there is a lack of dedication in the available workforce. I do see where some workers could say the same thing about employers. I know using temp agencies for extended lengths of time is rather popular right now.

That’s what monopsony seems like from an employer’s perspective.

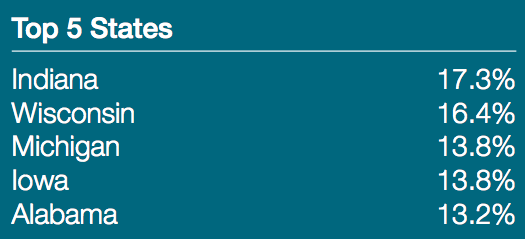

As an aside, manufacturing is no longer concentrated in the old rust belt. Iowa is more of a manufacturing state than Ohio, and Nebraska and South Dakota are more manufacturing intensive than Pennsylvania. Here are the top five states, in terms of share of the workforce in manufacturing:

Indiana has 3.6% unemployment, Wisconsin has 3.2%, and Iowa has 3.1%. That’s the job market in America’s most manufacturing-oriented regions.

Now I’d like to see a reporter interview unemployed workers in these three states, to get a sense of why they cannot find jobs. Maybe sit them in a room with a few employers, and try to get to the bottom of this issue.

Update: Rick Newman has another piece that explains why many workers are reluctant to move for a new job—distrust of companies who may later outsource their job overseas.

READER COMMENTS

Rajat

Jun 13 2017 at 9:41pm

I would be interested in any comments you had on the relevance (if any) of a tight and imperfect labour market to calls for higher minimum wages, since monopsony power is the standard reason left-liberal economists give for higher minimum wages. It seems to me that unless government is willing and able to set tailored minimum wages for each skill level at each firm, it is very difficult to ensure that higher minimum wages would not reduce hours worked, even if monopsony power was widespread. In Australia, our Fair Work Commission does set minimum ‘award’ wages across a wide variety of job designations, but of course it doesn’t seek to tailor those regulated wages to individual workplace conditions. As a utilities economist, I would draw an analogy with economic regulation of infrastructure. Sure, it may be beneficial to cap the prices charged by natural monopolies, but every single firm in the economy holds some degree of market power. That means that in theory there are welfare gains available from capping the prices charged by each and every firm. But we don’t do that, because in most cases it would create larger distortions than it would fix.

John Hall

Jun 13 2017 at 11:43pm

“many workers are reluctant to move for a new job—distrust of companies who may later outsource their job overseas”

I assumed everyone knew this already, except Tyler Cowen…

Jeremy Bancroft Brown

Jun 14 2017 at 1:08am

At the risk of being somewhat obvious, it sounds like this employer is reluctant to offer wages that would necessitate substantial raises within his existing workforce, i.e. the monopsonistic marginal cost of labor is pretty high. Also, custom machining is a delicate niche. Small prototyping orders don’t make money but can build a relationship, and big orders go to manufacturers who can do scale at low marginal cost. In between, medium-run orders and contracts can be profitable but are probably somewhat sporadic. Without access to big-business / software-startup-esque lines of credit, one would have to manage one’s fixed labor costs quite aggressively. Put another way, the lack of hypothetical scalability of this business limits the availability of financialization tricks that can better match the maturities of revenues and liabilities as the business expands. It’s not a very leveraged business so hiring is necessarily cautious.

Mark Paskowitz

Jun 14 2017 at 2:38am

I get your point that perfect competition is an idealised model, but I don’t understand why you think this looks more like monopsony. At no point did he say that he isn’t offering higher wages because he’d have to raise the wages of existing employees; he says new employees wouldn’t be worth it. A key impact of monopsony is under-hiring, and a key remedy I a minimum wage. Here, the labour market is tight and it doesn’t sound like a minimum wage would help at all.

So how do you distinguish this from a simple MC>MR story?

Thinking it through a bit myself, it sounds like the issue is fixed costs of adding a new employee (search and training) are significant. I suppose this leads to AC>MC and thus monopsony? But I still don’t see how a minimum wage helps this, so is that the weak link?

Luis Pedro Coelho

Jun 14 2017 at 3:45am

Don’t talk about the labour market, talk about labour markets. There can be a shortage of apples and an oversupply of tomatoes.

Daniel Kuehn

Jun 14 2017 at 7:50am

Mark Paskowitz –

re: “So how do you distinguish this from a simple MC>MR story?”

Well it is a simple MC>MR story. Monopsonists follow the exact same marginal conditions that competitive firms do.

Mark Paskowitz

Jun 14 2017 at 9:58am

Daniel,

Well, sure, but that doesn’t tell me why Scott is invoking monopsony here as opposed to “Labour markets are tight and the cost of a new employee has gone up.”

I understand that perfect competition is an idealized model. So is monopsony. I’m trying to understand exactly why monopsony is supposed to be a better (and sufficient) model in this case.

Scott previously wrote about a case where the employer couldn’t wage discriminate, so paying more to attract a new employee meant raising wages across the board. This interview doesn’t mention that at all.

Scott Sumner

Jun 14 2017 at 11:00am

Rajat, That sounds right to me. Matt Rognlie pointed out that studies consistently show that minimum wage increases are passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices. In the monopsony defense of the minimum wage, the key assumption is that higher minimum wages do not raise prices.

My own view is that at rates typically seen in the US, minimum wages don’t do much good or much harm. But I think that substantially higher minimum wages would do harm, even to workers.

Mark, Good point. Perhaps I misread it, but I thought he was referring to wage increases to all employees in an attempt to get more workers, in the numbers he cited. You are right, we’d need more information to know for sure if this was actually a monopsony problem, and not just a tight labor market. But the labor market he depicted, from his perspective, sure seemed like an upward sloping supply of labor.

On the minimum wage, see my response to Rajat.

Luis, Certainly, and I did mention that Indiana was unusually tight.

baconbacon

Jun 14 2017 at 11:23am

Perfect competition isn’t about prices, it is about profits. Being able to increase prices by 1 cent doesn’t indicate monopoly power at all unless profits also increase*. If you increase prices and it leads to a decrease in profits you very clearly do not have monopoly power.

*You could argue that increasing prices and having profits stay the same is monopoly power, but that sounds more like moving along a demand curve than a monopoly.

Mark Bahner

Jun 14 2017 at 12:17pm

That would be interesting! (Especially the part about getting unemployed and employers in a room together.) Please let us know if you see anything like that.

john hare

Jun 14 2017 at 5:35pm

A lot of people are basically unemployable. Even beyond the restrictions imposed on us by government, insurance, and liability issues, too many are willingly unproductive.

We can’t use people with criminal records in many locations. Insurance requires us to drug test so we can’t hire some people even for the work they are qualified for. Liability from sue happy people is a real problem.

To me. it is worse with people that think we owe them a living and the companies only exist to exploit them. The company is the enemy to them. People with that attitude will cause problems far in excess of any production they might contribute. I think there would be less of those if there weren’t so many indiscriminate safety nets.

Matthew Waters

Jun 14 2017 at 7:53pm

Something doesn’t track here. He admitted that he as been able to fill customer orders and is not turning down orders. He only said he “will have to reevaluate that at some point.”

So, how is there a labor shortage if he has enough labor? It seems like a basic question. It’s possible salaried employees are worked too long to be sustainable, but he didn’t say that’s going on now.

IMO, I don’t think the business has a monopsony but he wishes it was one. He only said it was a “struggle to hire people,” which seems like the inherent frictions of the market.

gmm

Jun 14 2017 at 8:46pm

Scott, please educate me.

I really don’t understand why this is used as an example of monopsony power.

You wrote

But it seems like this business may be very close to the situation where if they reduce wages by one penny per hour, they may indeed lose all their employees. Because it seems that their employees should have many other businesses wanting to hire them at their previous, higher wage.

I am not very educated in economics, so forgive the stupid question, but if you could lay it out for me, I would be most grateful.

Terran

Jun 14 2017 at 11:04pm

For the opposite side of this, see also the book “Why Wages Don’t Fall During a Recession” by Truman Bewley.

Kevin Erdmann

Jun 15 2017 at 12:29am

Am I getting this right?

If the firm was a price taker, like, say, a bakery is a price taker for flour, the firm could hire as many workers as he wanted at the market price. So, the fact that the firm has workers at its current wage, but can’t add to its workforce without increasing its price of labor means that it isn’t a price taker. Its demand for labor affects the local price.

Kelly

Jun 15 2017 at 12:37am

By the same token, a lot of companies aren’t worth working for. Maybe a bad location, maybe poisonous morale, maybe unrealistic expectations by management, maybe low wages, etc.

Now combine these ideas. If enough people can’t be employed we’ll see higher unemployment rates. If enough people won’t work for certain companies, we’ll see employers complaining about poor labor supply.

Simply looking at the unemployment rate in isolation, or listening to companies complain about tight labor supply, in isolation, doesn’t tell the rest of us the whole story.

john hare

Jun 15 2017 at 5:02am

@Kelly

I certainly agree that many companies are not worth working for. There are plenty of people that won’t or can’t work construction with my company. For anyone with enough market value to get a better job, I can’t blame them at all. For those actually unable to handle the conditions, I understand. It is the ones that are capable of doing something that won’t work for any company that bug me.

Anything in isolation doesn’t tell the whole story, as in Scotts’ reasoning from a price change. If there are 100 machinists total, wages can be a million a year and still not create more than 100 machinists in the near term from the local area.

Scott Sumner

Jun 15 2017 at 10:02am

bacon, I don’t agree, I am going with the textbook definition. In any case, if you have pricing power, there is always some price where an increase in price raises profits, and some price that does not. And that’s equally true of a pure monopoly.

John Your final sentence is the key point.

Matthew, You said:

“So, how is there a labor shortage if he has enough labor?”

He says that he does not–he wants more employees.

gmm, That’s possible, but does that really seem plausible to you? Not to me.

Kevin, Yes.

gmm

Jun 15 2017 at 10:48am

Thanks Kevin, you answered my real question about why this is an example of monopsony power. And thanks Scott for replying to me and to Kevin.

Comments are closed.