Here’s Tyler Cowen:

Many monetary rules call for higher rates of price inflation if the economy starts to enter a downturn. That’s often the right economic prescription, but voters hate high inflation.

Tyler is engaged in “reasoning from a price change”. A term like ‘inflation’ doesn’t mean much of anything to the public, and certainly not what economists like Tyler mean by the term. When I used to poll my students, I’d find that 99% of students conflated ‘inflation’ with supply-side inflation. I’d ask, “Suppose all wages and prices rose by exactly 10%, has the cost of living actually increased?” I’d guess 99% would get the answer wrong. (Yes, the cost of living has increased, but they’d say no.)

When the public expresses a concern about inflation, what they really are referring to is living standards. Thus when there is supply-side inflation, prices rise faster than incomes, and living standards fall. That’s the type of inflation the public has in mind when they express opposition to inflation. In contrast, when there is demand-side inflation the public sees their income rise faster than prices, so living standards rise (in the short run.)

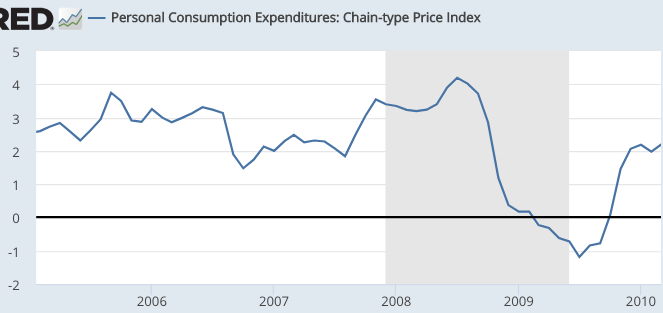

If the public really did oppose demand-side inflation then they should have greatly enjoyed the economy of 2009. After all, a fall in AD brought inflation down to zero. And yet living standards plunged, because the demand-side disinflation caused incomes to fall faster than inflation. If the Fed had a more inflationary policy during 2009 then the public would have been much happier, as there would not have been as big a decline in real income. A much milder recession and less severe asset price collapse.

Did voters prefer the economy of 2006 or 2009?

Again, never reason from a price change. How people feel about a price change depends entirely on whether it’s caused by an aggregate supply shift or a demand shift.

In addition, don’t take seriously the answers you get from polls of public opinion. When you ask the public how they feel about inflation, they are (in their own minds) holding their own nominal income constant and visualizing rising prices. No surprise that that isn’t popular! Thus their answer doesn’t really tell you what they think about inflation, and certainly not what they think about demand-side inflation created by the Fed. Rather their answer tells you what they think about supply-side inflation. Yes, we all hate adverse supply shocks. But beyond that the public has no opinion, as they don’t really even understand what inflation is.

PS. Also, don’t confuse incomes with hourly wages. An unexpected demand-side inflation lowers real hourly wages while raising real incomes and real asset prices. People care far more about their overall real incomes and real asset prices than they do about their real hourly wages.

PPS. The first time I ever recall a politician running on an explicit platform of higher inflation was in 2012. Abe won a massive victory on a promise of higher inflation, in a country where a huge share of voters are old people on fixed incomes. He ended deflation in Japan and was re-elected overwhelmingly. (We’ll see how he does this time.)

READER COMMENTS

Michael Stack

Oct 20 2017 at 5:57pm

Color me stupid but I’d agree with your students. The price has increased, but not the cost.

This ignores complexities like existing weatlth (which is worth less now that prices are higher) or menu cost adjustments. It also assumes I’m employed at that increased wage.

What am I missing?

Scott Sumner

Oct 20 2017 at 6:05pm

Michael, You are missing several things.

When prices rise by 10% then the cost of living has increased by 10%, regardless of what happens to wages.

Monetary stimulus often increases real wealth, as nominal wealth rises faster than prices.

The unemployed gain more than average from demand-side inflation, as it increases their chance of getting a job.

Kevin Erdmann

Oct 20 2017 at 7:26pm

“Did voters prefer the economy of 2006 or 2009?”

Hmm. The public overwhelmingly blames 2009 on inflation in 2006, in agreement with the economists polled in the recent IGM forum. I don’t think they prefer deflation.

I think you have a good broader point, but the current context seems a bit more blinkered than that.

A religious masochist doesn’t prefer self-flagellation. Their problem isn’t that they like to hurt themselves. It’s that they believe they are also hurting demons.

Mark

Oct 20 2017 at 7:29pm

If prices go up by the same amount that wages go up, am I not exchanging the same number of hours of work for the same kind and quantity (and quality) of goods and services? And therefore, my cost of living, in my own man-hours, has remained the same.

My understanding of what you’re saying is that a wage increase does not lead to an immediate corresponding price increase? (I’m not sure where ‘wealth’ is coming from, are we still walking about wages?)

Which might be the case. But all that seems to mean is that if a perfectly corresponding price increase occurs with a given wage increase, that the wage increase must not be the only factor in play; something else must be driving prices to make them seem to match the wage increase. But whatever those factors are, if prices increase by the same amount as wages, regardless of whether the price increase was not solely caused by the wage increase, then how has the real cost of living not remained the same? Am I not working the same number of hours at the same job to buy the same quantity of bread?

jj

Oct 20 2017 at 9:39pm

Tyler might be right about public perception, but there’s a really easy fix.

“Why no, our monetary rule doesn’t call for higher rates of price inflation in a downturn — it calls for higher wage growth!”

Save your breath explaining how they’re two sides of a coin, just show ’em the good side.

Andrew_FL

Oct 20 2017 at 9:54pm

Huh? If I have a job already, I am earning a fixed nominal wage, and am working a fixed number of hours, how can my real income increase if my real wage is falling?

Sure, real incomes can rise for people who do not have a job, who are subsequently able to get one-and by a lot, from zero (assuming they are collecting no non market income) to, whatever income their job brings in. In a severe recession maybe 10% or so of the civilian labor force falls into the category. The other 90% of people who want to work would see their real incomes decline if real wages fell.

Kevin Erdmann

Oct 20 2017 at 9:55pm

To put a finer point on my previous comment, the historical example in your defense is William Jennings Bryan. That is a populist position, and clearly there the populists understood the advantages to them of inflation.

The mystery today is, “where is our Bryan?” Surely, debtors should have liked paying down those supposedly bloated debts with less valuable dollars.

The complaints against the Fed in 2009 weren’t, “you are trying to increase our cost of living by 2%, and we don’t like that.”, they were, “you are bailing out Wall St.” And, you can see this in Bernanke’s and Geithner’s memoirs. They aren’t trying to justify to their readers how 2% inflation helps them. They are defending themselves by trying to assure us that they really, really wanted to hurt Wall St. as much as we did, but they couldn’t help us without helping Wall St., too.

So, I think you are right to critique Tyler, but that isn’t the reason people hate inflation. People hate inflation because an economy based on economic rent seeking means that nominal growth will accrue to the rent seekers, and that is what they don’t like. The problem is that nobody has come to terms with the core source of those rents.

Scott Sumner

Oct 21 2017 at 1:09am

Kevin, Good point.

Mark, Don’t overthink this. If prices rise by 10% then the cost of living goes up by 10%. Wages have nothing to do with it. The rate of inflation is the percentage change in the cost of living.

Andrew, Were most people better off in 2009? Because that’s the logic of your argument.

Mark

Oct 21 2017 at 3:05am

“The rate of inflation is the percentage change in the cost of living.”

Ok, that’s straightforward. I guess I tend to forget that you like nominal variables.

Andrew_FL

Oct 21 2017 at 4:02am

You are letting your intuition override basic common sense here, but plenty of people who saw their real income increase were nevertheless worse off in their material wealth.

The “logic” of my argument is math. If 10 people have jobs making 10 units of nominal income and all other prices drop 10% and one of them loses his job, nine out of ten of them have seen their real income increase and one of them has seen it drop to zero. They are each 11% better off and he is 100% worse off. Average real income is unchanged in this hypothetical. If you mess around with the choices of numbers you can get the average real income to decrease, of course. If, say, prices only fall five percent and one out of ten lose their jobs, real income one average decreases about 6%. Nine out of ten people never the less see their real income rise in that scenario.

Andujar Cedeno

Oct 21 2017 at 4:44am

[Comment removed. Please consult our comment policies and check your email for explanation.–Econlib Ed.]

Max

Oct 21 2017 at 6:24am

I think the public is still right, if inflation is presented by the CPI and the public sees their wages stagnate (in the median) while the CPI rises.

At least, this is what I see here in Germany. Wages stay sticky mostly and prices increase, especially rent and energy. The influence monetary inflation has here is probably low in a direct way (devaluation of the currency), but indirectly it is repsonsible for a larger part (ECB rate leads to more homebuilding because of cheap credite leads to expensive the housing situations).

Of course, maybe in a freeer society the effect would be smaller, but with all the regulations we have, the effect is accentuated.

In my opinion this is why students are not wrong, when they reply that inflation leads to being well-off.

I agree that a demand-side only inflation would be benefitial, but a) nobody takes that seriously (when did it happen?) and b) it is not a current issue.

Thaomas

Oct 21 2017 at 7:45am

We still do not have a good explanation of why the Fed acts as if it has an inflation rate ceiling. a) It could be that is has an inflation rate ceiling. b) It could be that it has a constraint on use of instruments that would have allowed it to achieve a 2% inflation target, e.g. more vigorous use of QR. c) It may be that it has a constraint on the instruments that would eventually be needed to bring the inflation rate down after the PL had returned to a target growth path, e.g. its banker constituency does not like rapid increases in ST interest rates.

The supposed public misunderstanding of “inflation” would figure only in a)

Scott Sumner

Oct 21 2017 at 10:33am

Mark, You said:

“I guess I tend to forget that you like nominal variables.”

It has nothing to do with what I “like”. It’s about the definition of terms. The cost of living is defined as the price level.

Andrew, Yes, but your “scenario” does not describe the real world. I’m pretty confident that most people were worse off in 2009. And I’m even more certain that Tyler is wrong about the politics. Voters did not seem to welcome Herbert Hoover’s huge reduction in their cost of living in 1932, when he lost overwhelmingly. And yet unemployment was “only” 25%

Max, You said:

“I think the public is still right,”

About what?

You said:

“In my opinion this is why students are not wrong, when they reply that inflation leads to being well-off.”

Students don’t believe that inflation makes people better off.

Alan Goldhammer

Oct 21 2017 at 12:19pm

The average voter has no clue about any of this stuff. I think I already posted about this over on Tyler’s blog so forgive me if this is a repeat that some of you have seen. Perhaps the best modern analysis of what voters do and do not think is the recent book by Achens and Bartels, “Democracy for Realists Why Elections Do Not Produce Responsive Government” I was a political science minor in college with an emphasis on American politics and had to spend a lot of time reading Angus Campbell and V.O. Key. The Achen and Bartels book is depressingly good in its analysis.

Everyone would do well to read it. As a bonus you would understand how a series of shark attacks in New Jersey affected the results of some local elections.

Effem

Oct 21 2017 at 12:54pm

Agree with Kevin. Nominal growth accrues to the population in ways the voters don’t like.

Andrew_FL

Oct 21 2017 at 2:27pm

Which part is wrong exactly?

Paul Johnson

Oct 21 2017 at 3:00pm

Real cost of living or nominal cost of living?

I’m guessing you had just taught the students about the difference between nominal and real prices and they assumed you were testing whether they could do the correction to real.

AMT

Oct 21 2017 at 3:16pm

Scott,

This is one where I think you get it wrong. People dislike inflation, they just also dislike decreasing living standards (which often matters more). But then ask people if they’d rather get a 2% raise and have prices increase 3%, or no raise and no price change, they prefer the raise with lower living standards, cause then “I’m appreciated at work!”

“But beyond that the public has no opinion, as they don’t really even understand what inflation is”

That is certainly true…and people hate things they don’t understand! They just see “stuff is more expensive so that’s bad.” And they know “pay raises for me are good,” but they have no way to compute what happens with both changing at the same time.

David Wright

Oct 21 2017 at 3:53pm

I also agree with your students.

First off, unlike “wage” or “GDP”, “cost of living” isn’t a well-defined term that you can look up in every textbook. If you want to produce a formal definition, you should choose one that is aligned with the intuitive meaning of the words as much as possible.

One possible formal definition would be “the number of hours the average worker needs to work to enjoy the average consumption bundle”, in which case your students are right, the value hasn’t changed.

Another possible formal definition would be “the monetary cost of the average consumption bundle”. In that case you might think you are right, the number value has changed, but you should be careful, because that value has units, and you can’t compare number values with disperate units. If you regard the units as time-t-dollars and time-(t+1)-dollars, and you take the standard view that one can convert between these units, then the values are the same, which you can see by converting them to like units. Your original assertion would be like saying your weight has gone up if you measure it in pounds instead of kilograms.

Scott Sumner

Oct 21 2017 at 7:02pm

Andrew, The part that implied most people are better off in a situation such as 2009, compared to a more more normal inflation rate.

Disinflation hurts people in many different ways, thinking in terms of hourly nominal wage rates is not helpful. Hourly wages are very different from income. Obviously much more than 10% of the US population was hurt by the disinflation of 2009.

Paul. There is no such thing as the “real cost of living”. That’s like saying “the real inflation rate”. It’s an oxymoron.

AMT, You said:

“But then ask people if they’d rather get a 2% raise and have prices increase 3%, or no raise and no price change, they prefer the raise with lower living standards, cause then “I’m appreciated at work!””

I think you are confused. I was the one arguing that the public doesn’t dislike inflation, not Tyler.

David, I’ve heard people use the term “cost of living” roughly 5000 times during my life, always in reference to the price level. If it has some other meaning then please show me where you get it.

I think you may be confusing cost of living with standard of living.

Andrew_FL

Oct 21 2017 at 7:22pm

Which is weird because I actually never implied this. In fact I explicitly stated the exact opposite.

All I said was that those who remain employed, maintain a fixed number of hours worked, and continue to earn the same nominal wage, have their real income increase if prices fall. The part of this I did not specify was the implicit assumption that income from their wage earning job is their primary or even sole source of income. Fair enough, the percentage of the labor force which both retains their jobs in a recession and earns only labor income is smaller than 90%. But I’m not as sure as you are that it is less than 50%. If you know any sources on this I’d appreciate them.

Todd Kreider

Oct 21 2017 at 9:55pm

In 2011 and 2012, Japan’s inflation rate hovered around 0%. Inflation was at 1% to 3% from late 2013 to early 2015 or around 15 months before dropping down to about 0% again for the past two years. I wouldn’t say Abe ended ended deflation since Japan is right where it was before Abe was elected in late 2017.

Press “10 years” to see this:

https://tradingeconomics.com/japan/inflation-cpi

2015 Jan to Mar 2.3%

[inflation spurt ends]

2015 Apr to Dec 0.3%

2016 -0.3%

2017 0.5%

Carola Binder

Oct 21 2017 at 10:06pm

From a historical perspective, isn’t it sort of strange to have an article with this title? Wasn’t it once so commonly understood that voters didn’t dislike inflation “enough,” that that was used as an argument for having independent inflation-averse central bankers? The whole premise of political business cycles was that politicians could get away with excessively inflationary policy right before an election.

François Godard

Oct 22 2017 at 4:37am

You make a great point Scott but not explicitly enough: the fact that individuals have a very rough notion of retail price inflation. At, say, below 5% p.a., most people are incapable of estimating whether it’s 0% or 5%, because inflation is a statistical aggregate produced by hundreds of qualified people working in a dedicated organisation.

To illustrate: the introduction of euro notes in 2002 was a PR disaster as the rumour mill and cheap journalism created the myth that retail price inflation had considerably accelerated. Opinion polls and anecdotal evidence at the time showed that a majority believed that, from all education levels and in most countries. This had enormous political consequences including the rise of populist anti-european sentiment in the noughties. European statistical bodies had to introduce new measures on “perceived inflation” to help fight back public opinion — and this was ages before fake news.

In other words inflation is also a cultural phenomenon and often a political issue regardless of hard data.

S D

Oct 23 2017 at 8:06am

I think the point is broadly correct, but there may be ‘restriction of range’ issues.

I have lived in times and places where inflation has ranged from -2% to +5%. People were happiest at the times of high inflation because real wages and employment were rising fastest. This chimes with Scott’s point.

But this is not a wide huge range of human experience.

Inflation which is high and/or volatile imposes a range of costs which people tend not to like.

I would much prefer 2% inflation with 3% nominal wage growth to 10% inflation an 15% nominal wage growth.

Jose

Oct 23 2017 at 8:34am

I agree with the central idea of the article, for low levels of inflation.

But being Brazilian and having lived through the estabilizaton plan in 1994, I can tell you that when the country is running hyperinflation voters DO CARE for low inflation, no matter what happens with real incomes.

Isaac Kogure

Oct 23 2017 at 3:42pm

I believe that “voters” do not have an opinion on inflation because it is on such a large scale. By that I mean that overall, since wages increase as prices increase there is no reason in most people’s minds to be concerned. That is until inflation becomes too high. As inflation increases the cost of production for businesses increases. Eventually, the loss in total revenue in these businesses will cause them to start laying off workers.

Inflation also decreases the value of the dollar. Even if inflation is not that high wouldn’t it still decrease the value of the dollar? The buying power a country has in the world economy is directly affected by inflation as well as deflation. Ultimately, “voters” should care inflation. In my mind, as a country’s economy prospers and becomes increasingly wealthy the same should happen with the citizens/ “voters” of that country.

Comments are closed.