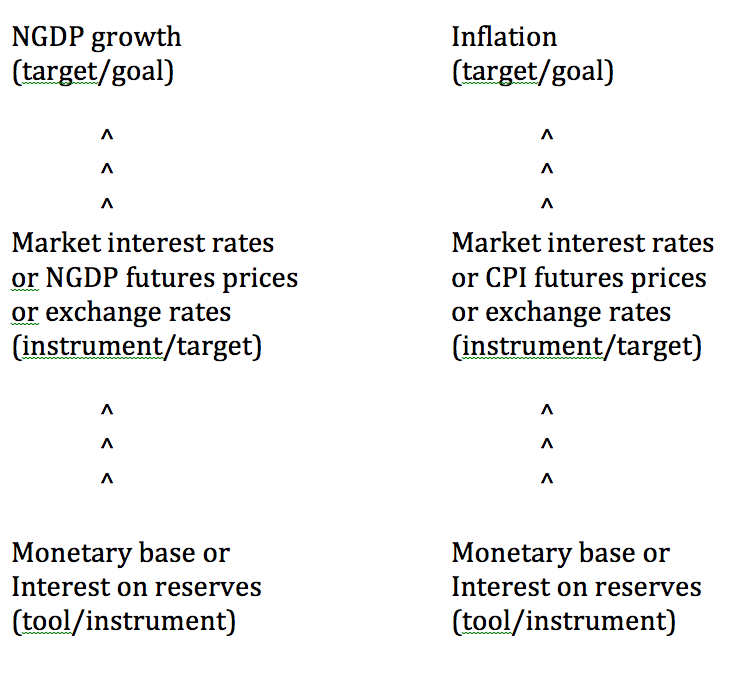

As if monetary policy is not confusing enough, the terminology is also ambiguous, with terms used in inconsistent ways. For instance, is the Fed targeting interest rates, or are they targeting inflation? Consider the following flow chart, showing two possible monetary policy targets. At the bottom you have the actual tools that the central bank can use to influence policy. In the middle you have flexible market prices that they may try to control, with the long run objective of stabilizing growth in NGDP or the price level (on top):

The term ‘instrument’ is sometimes used for variables that the central bank directly controls, like the monetary base, and at other times is used to describe the intermediate target of these open market operations, say the fed funds rate. The term ‘target’ is sometimes used to describe the intermediate target of policy (say interest rates or exchange rates) and at other times is used to describe the goal of policy, say inflation or NGDP.

Because of this confusion, people often end up comparing policies that are on entirely different levels. Thus I’ve seen people contrast the Taylor Rule with NGDP targeting, which makes no sense. The Taylor rule describes the middle level of the process, whereas NGDP targeting is about the policy goal. You could compare NGDP targeting to inflation targeting, or you could compare the Taylor Rule to a futures price target, or an exchange rate target.

I can’t do anything about this confused terminology, other than make others aware of the problem.

I recently gave a talk at the Mont Pelerin Society meetings in Ft. Worth, and there were a number of questions. One person asked why the Fed should control interest rates. We generally assume that the market does a better job setting prices than does the government.

There are actually two issues here. Should the government have any involvement in the monetary system, and if they are involved, should they “control” interest rates? My views on this are a bit hard to explain. So bear with me as I try.

For simplicity, I’ll assume the government is involved in monetary policy, and then explain the options once that decision as been made. My first claim is that monetary policy always involves the government setting a price or a quantity. They might control the quantity of base money, or M1 or M2. Or they might control the interest rate or the price of foreign exchange or the price of gold (as in the 1920s), or the price of NGDP futures contracts. But if you control monetary policy, you control some sort of price or quantity. Notice that this is even true of a laissez-faire gold standard where the government merely defines the dollar as a fixed quantity of gold, and lets free banks issue currency in an unregulated fashion. The government is still (implicitly) determining the gold price, although in a pure unregulated gold standard they do so merely by defining the dollar as, say, 1/20.67 oz of gold, not “targeting” the price with open market operations.

As many of you know, I oppose interest rate targeting; that’s one price I’d prefer the Fed not target. And yet I do not oppose this policy for the reasons I oppose price controls, rent controls, minimum wages, agricultural price supports or any similar policy. Monetary policy does not move the interest rate away from “equilibrium” in the microeconomic sense of that term.

Here is a point I cannot emphasize strongly enough: There is no microeconomic analogy for what’s going on in macroeconomics. Consider two policies:

The Mexican government replaces 100 old pesos with 1 new peso

The Mexican government suddenly increases the money supply by 10%

The first example causes all wages and prices to immediately decline by 99%. But interest rates don’t change.

The second policy causes prices to gradually increase. Because prices are sticky, or slow to change, interest rates also fall in the short run. There is no microeconomic analogy for this “liquidity effect”. It occurs because interest rates are the flexible price that adjusts due to the fact that other prices are sticky. In contrast, the 100 to 1 Mexican currency reform eliminates all price stickiness and hence interest rates don’t change at all. All Mexican prices immediately fall by 99%

With this in mind, I’m going to try to convince you that the Fed doesn’t actually “control” interest rates in the sense that you might believe they control interest rates. I’d like you to imagine two identical countries, in parallel universes, one of which targets interest rates via changes in the monetary base, while the other targets exchange rates via changes in the monetary base. In each case, the ultimate objective (goal) is 2% inflation. In each case, the central bank moves its intermediate target to a position that it believes will best achieve 2% inflation. Importantly, the two central banks do not tell the public whether they are targeting interest rates or exchange rates. They just do it.

Each day, the two central banks instruct their open market desks to adjust the monetary base until the intermediate targets (interest rates or exchange rates) are at the desired level by market closing. In both cases, the public is completely unaware of whether they are targeting interest rates or exchange rates. But all central bank actions are fully transparent. The public knows the size of the open market operations, and they know where the exchange rate and interest rate end the day. But they can’t tell which bank is “controlling” interest rates and which bank is “controlling” exchange rates. It’s all in the head of the two central bankers.

1. In both cases, monetary policy decisions affect both interest rates and exchange rates.

2. In both cases, the central bank need not intervene directly in either the foreign exchange or credit markets. They may choose to so, but it’s not essential. They just need to somehow inject and remove money from the economy, which impacts both exchange rates and interest rates.

3. In both cases, the macroeconomy (labor market) may or may not be in equilibrium, depending on whether monetary policy is conducted well.

4. In both cases, the foreign exchange and credit markets will be in equilibrium even if the macroeconomy is not in equilibrium. In other words, I assume that nominal wages are sticky, but nominal exchange rates and nominal interest rates are not sticky.

The central bank that targets interest rates is not “controlling” them in the sense that a government might control rents or gasoline prices, and it’s not even directly intervening in the sense that the Saudi government might influence oil prices by reducing oil output, or the US government might influence wheat prices by purchasing surplus wheat. It is directly intervening in the money market, and interest rates are only impacted because prices happen to be sticky in the short run. But even central banks that do not target interest rates, such as those that target the money supply or exchange rates, still do influence interest rates. If the two central banks in these parallel universes both happened to have perfectly effective policies, then the path of interest rates would be identical, even though one central bank is “controlling” interest rates and the other is not.

Think of interest rates as a sort of guidepost used by the Fed, to help them offset money demand shocks. At a fundamental level, monetary policy is about adjusting the supply and demand for base money to keep inflation at 2%. But most central banks believe it is easier to do so if they have intermediate targets, such as interest rates or exchange rates (I prefer NGDP futures prices.) Interest rates are the middle step of this process, but the essential nature of the process doesn’t really involve interest rates at all. It’s about setting the supply of base money at a level that the central bank thinks will lead to on-target growth in the goal variable (inflation or NGDP growth).

Of course you are quite free to continue asserting that central banks “control” interest rates, even if I worry the phrase is misleading. But if you do so, you need to remember that none of your intuition about why governments should not control prices has any applicability to interest rate targeting. I actually think interest rate targeting is a bad idea, but for completely different reasons from the traditional “government intervention is bad” reasons. I don’t believe that interest rates are a useful guide to monetary policy. While I don’t worry about credit markets not being in equilibrium, I do worry about the labor market not being in equilibrium.

A better intermediate target is NGDP futures prices. If the monetary base is adjusted in such a way that NGDP futures prices stay close to a 4% growth rate, then the labor market will stay close to equilibrium. Whatever path of interest rates that results from this is appropriate.

READER COMMENTS

Benjamin Cole

May 23 2019 at 9:19pm

Interesting question: as capital markets globalize, does any particular central bank lose influence?

Are interest rates set globally by supply and demand? That seems like a reasonable proposition

So when we speak of “monetary policy” should we speak also of the ECB, the Bank of Japan, and the People’s Bank of China? Maybe add in the Bank of England.

Other practical and institutional conundrums: by some estimates there are $32 trillion stuffed into Cayman Island-style offshore bank accounts. Wither this ocean of money, which is nothing more than blips on computer chips ( indicative of potential but not actualized real demand for services and goods) and can be transferred hither and yon in an instant?

By the way, there is $280 trillion worth of real estate globally.

Okay, some big numbers out there. And a particular central bank wants to buy or sell $1 trillion in bonds on globalized markets? And that action accomplishes what?

Thaomas

May 25 2019 at 6:39pm

As long as currencies are differentiated, monetary policy can be, too.

Philo

May 26 2019 at 5:06pm

‘Wither’ almost makes sense, but I think you meant ‘whither’.

But what difference does it make whether dollars in Cayman Island bank accounts are transferred elsewhere?

Ethan Rahman

May 24 2019 at 10:08am

Hi Scott, I’m a bit confused.

Right now, the Fed changes the Federal funds rate target over the course of several months to hit its policy goal – inflation.

Would NGDP (or PCE) futures targeting entail the Fed adjusting the target price of NGDP futures contracts? That seems very different from what you’ve written else where.

Thaomas

May 24 2019 at 2:54pm

Sorry, but I still do not think we know that the Fed actually has a symmetric 2% inflation target as the price component of their dual mandate. What evidence do we have to reject the hypothesis that they still have a 2% inflation ceiling?

Do we understand by “gold standard” that the Fed would maintain a 0% rate of change in the price of gold? It could have a gold price target that rises by X% p.a. where X is chosen to maximize real income over time given price stickiness, the size of expected shock that require relative price changes and the effect of X on the ability to forecast relative price ratios in the future. And would a “gold standard” for prices rule out the employment portion of the Fed’s mandate?

Scott Sumner

May 25 2019 at 5:05pm

Thaomas, We don’t know, as you say. But since 2000, inflation has been above target a number of times; it’s worse of you restrict the period to post-2008

Thaomas

May 25 2019 at 6:53pm

But isn’t the key whether market participants ever see efforts to bring up inflation when it has been below target, explained as, “Oops we undershot our inflation target again so we re-calibrated our model and now believe that we should increase the QE purchases from $x billion/mo. to $y billion (or lower the interest paid on reserves from x% to y% or increase foreign exchange purchases form c to d, or whatever instrument they think will be effective).” The question is can we reject the hypothesis that the Fed has a 2% ceiling.

Bob Murphy

May 24 2019 at 3:10pm

I don’t agree with everything in this, but I appreciate what you’re doing in this post, Scott.

Scott Sumner

May 25 2019 at 5:03pm

Bob, Appreciation is the first step to enlightenment. 🙂

Seriously, I find this a difficult issue to explain in words, and it’s probably not my final attempt.

Comments are closed.