Many people would regard my approach to teaching monetary policy during my final years at Bentley to be hopelessly “out of date”. Marginal Revolution University has a new video out that discusses new ways of teaching Fed policy in light of changes made during and after the Great Recession. Here I’d like to push back against this new view.

Early in the video, Tyler suggests that the Fed traditionally relied mostly on open market operations, and then during the Great Recession it discovered that it needed new tools to achieve its goals. Tyler mentioned quantitative easing, interest on bank reserves, and repurchase agreements (as well as reverse repurchase agreements).

But is there actually any evidence that the Fed needed new policy tools?

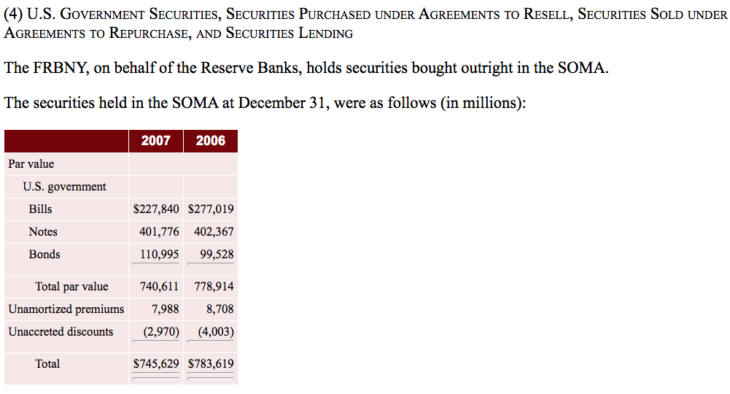

Tyler mentions that the Fed traditionally purchased T-bills in its open market operations, and that quantitative easing allowed it to purchase much longer-term bonds. But is that correct? This data suggests that even before the Great Recession, T-bills were only a modest portion of the Fed’s balance sheet:

In my view, “quantitative easing” is nothing more than big open market operations. You might quibble that the purchase of MBSs was something new, but since these bonds had already been effectively guaranteed by the Treasury, they were very close substitutes for the long-term T-bonds that the Fed already held in its portfolio. Instead of a brand new way of teaching money, we simply need to add a couple words on MBSs to the textbook definition of open market operations, which is the buying and selling of bonds with base money. Repurchase agreements have the same sort of impact on the monetary base, but it’s a technical innovation that isn’t really important for undergraduates. Rather you want them to focus on the essence of what monetary policy–exchanging money for bonds.

There is one new policy tool that is both distinctive and important—interest on bank reserves. While I’m no mind reader, I sensed that Tyler struggled with the question of how to explain this tool. At the beginning of the video, Tyler suggested that these new tools were instituted by the Fed to address the special problems that arose during the Great Recession. Then right before explaining interest on reserves, he noted that the Fed had trouble stimulating the economy during the long period of near zero interest rates after 2008.

I hope you see the problem. Interest on bank reserves is a contractionary policy, and does nothing to address the special problems associated with the sort of liquidity trap that was used to motivate the discussion. Indeed the Fed was provisionally granted permission to use IOR back in 2006 (with a 5 year delay), when interest rates were fairly high.

Just to be clear, Tyler doesn’t say anything about IOR that is incorrect. After motivating the IOR discussion with some comments on the zero bound issue making open market operations much less effective, the actual example of interest on reserves that he cites is from 2015, when the Fed raised IOR to prevent the economy from overheating.

In retrospect, the Fed clearly raised IOR too soon, but that doesn’t mean it’s a bad example to use. The 2015 example does illustrate how IOR works in a technical sense. My bigger complaint is that the video gives the impression that the Great Recession created a need for new policy tools, and there isn’t really any evidence that this is the case. Quantitative easing is not really a new tool, it’s an old tool used much more aggressively. And IOR is a highly contractionary policy, and thus whatever its merits its not something you want to start doing 10 months into the worst recession since the 1930s. But that’s exactly what the Fed did.

I sympathize with instructors. It must be confusing to teach the truth—that the Fed blundered in late 2008 (as even Ben Bernanke admitted in his memoir.) It’s much easier for students if you teach these new tools as logical innovations to deal with specific new problems. Unfortunately, the easy way to teach monetary policy doesn’t happen to be true.

PS. This critique is aimed at a new MRU video, but it’s equally applicable to many new economics textbooks, which treat the Fed as the hero of the story, not the villain.

PPS. If you want to teach about new expansionary policy tools for the zero bound, you should ignore the Fed and instead discuss the policy of negative IOR in Europe and Japan.

READER COMMENTS

marcus nunes

Jun 29 2021 at 2:43pm

Sometimes, professors do a disservice just to remain being considered “mainstream”.

Remember in the Spring of last year when avowed monetarists affirmed that the “explosion” in money supply growth would give rise to inflation after a “suitable” period? In fact, they should have asked: Will the Current Money Growth Acceleration Help Avoid a Second Great Depression?”

Here´s a story about the “one-legged” monetarist https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/how-the-inflation-story-changes-when

Rajat

Jun 29 2021 at 6:04pm

Hi Scott, sorry, this is off-topic, but you may be interested in this – the RBA has just published a survey on high school students’ perceptions of studying economics.

The key themes are: most high school economics students are male (and increasingly so), go to private schools and are from higher socio-economic demographics. Economics is perceived as hard work for the marks (we have external subject exams at the end of high school that generate scores that our university entrance selection processes are highly dependent on). It is also perceived as less interesting and less relevant to future careers than ‘business management’, a more vocational subject introduced in the early 1990s that led to a dramatic decline in the numbers of economics students. I don’t think that’s necessarily a bad thing – economics is an abstract subject and even basic demand and supply is probably beyond the grasp of many less able students. Perhaps it shouldn’t or needn’t be.

Part of the problem is no doubt that many teachers are not well-equipped to teach economics and the RBA identifies this. A bigger problem is that the course (at least in my home state of Victoria) has barely changed since the 1980s when I did it. It still devotes considerable time to the individual components of the balance of payments, harking back to the days when Australian policy-makers fretted over the current account deficit. And of course, the macro elements of the course are almost entirely concerned with Keynesian AD analysis and its various components. Naturally, that makes the content seem quite dry and mechanical. Although as Nick Rowe once said, students love their ‘concrete steppes’:

In 2015, I was on the curriculum review panel for Victoria’s high school economics course and the resistance to updating the material was enormous. The discussion of monetary policy was entirely centred on interest rates. When I suggested that maybe it should also refer to the money supply and QE, other panel members – mainly high school teachers who themselves were comfortable with teaching the same material they were taught 10-30 years earlier – confidently asserted that none of that would happen in Australia. That’s when the RBA’s cash rate was 2%. Even prior to the pandemic, the cash rate was (belatedly) down to 0.75% and the rest is history.

I’m interested in your views on the way high school economics is taught in the US and whether it suffers from similar problems. My university lecturers scoffed when people mentioned having studied high school economics, as if it were a totally different subject. That wasn’t my experience. I found they effectively employed the same IS-LM model.

Colin Haller

Jun 30 2021 at 10:52am

The great damage wreaked by high school Economics (which goes double for undergraduate Economics) is its presentation as a field outside of the Social Sciences.

In this way all sorts of normative assertions get buried in the unexamined assumptions underlying the equations offered as somehow equivalent to those in Physics or Mathematics.

Much mischief ensues …

Scott Sumner

Jun 30 2021 at 11:49am

Economics is certainly a difficult subject for most students. Most people will never really understand the key ideas. Steve Rubb and I recently wrote an introductory Econ textbook, in case you are interested in how I’d teach macro. But even there, I had to make compromises to cater to the professors that would assign the book.

But at least I covered the money supply, never reason from a price change, monetary offset, etc.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 29 2021 at 6:10pm

Why would it be difficult to teach that the Fed blundered in 2008-20. That’s what one would teach about the Great Depression, the post-War inflations, the Nixon-Burns inflation, etc. (unless one thinks those inflation rates were optimal for the time and place).

Scott Sumner

Jun 30 2021 at 11:51am

It’s not difficult in a technical sense, it’s more of a psychological issue. It’s easier if you tell students “Here’s what the Fed does and why”, than “Here’s what the Fed is doing and here’s why it’s wrong.”

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Jun 29 2021 at 6:17pm

And even if the total amount of stimulus in 2008-29 was insufficient to keep NGDP (or some other combination of inflation and real growth) on track might the use of “QE” + IOR arguably OK as a way of shielding the MM funds from <0 returns? IOR could have been combined with even larger purchase of long term assets to achieve the Fed’s mandates

Scott Sumner

Jun 30 2021 at 11:59am

They could have done that with 5 basis points of IOR, but the actual rate was closer to 100 basis points in October and November 2008.

dlr

Jun 30 2021 at 8:24am

Interest on bank reserves is a contractionary policy

since we’re talking about teaching, is it really though? i would not teach higher IOR as intrinsically contractionary. take a CB who raises IOR without any stated intention to tighten. market participants now get a higher return on reserves but the future monetary base is, ceteris paribus, higher due to the fed paying the IOR. just like a stock dividend. the new nominal equilibrium is not obvious.

sure, you can assume that the fed offsets the future mb increase, but this is not a prosaic assumption. after all, if the fed is targeting inflation and using ior as its main tool, then it is not at all clear that market participants should expect said offset. teaching ior as intrinsically anything runs into the same sort of danger that leads to unhelpful neofisherian perspectives: it omits expectations about future fed actions, the most important part. this was a lot more forgivable when it came to omo, because the intent was much more obvious and there was no weird ceteris paribus tension. even then, i think the “hydraulic” methods of first teaching the mechanics of policy and only later teaching concepts like equilibrium selection is partly responsible for all the oversimplified partial equilibrium thinking out there, including things like “lower interest rates means policy is loose.” it’s not a good idea to separate ior from the reaction function. never reason from a device change.

Matthias

Jun 30 2021 at 11:33am

The Fed transfers its profits to the treasury.

If paying interest on reserves means that the Fed makes less profits, that means it won’t send as much money to the treasury.

IOR thus doesn’t increase the expected future money supply.

Scott Sumner

Jun 30 2021 at 11:57am

Your argument would apply equally well to any Fed policy tool. More than one tool can change at a time. Nonetheless, students need to learn that open market sales are contractionary, ceteris paribus, higher IOR is contractionary, ceteris paribus, and higher reserve requirements are contractionary, ceteris paribus, before they can even understand the more sophisticated analysis that you are describing here. Don’t forget that going in students typical know NOTHING about Fed policy.

But you are correct that the mere fact that the money supply decreased, or the mere fact that IOR increased, doesn’t prove that monetary policy has become more contractionary. You must look at the entire picture.

Jeff Hummel

Jun 30 2021 at 12:51pm

When I teach interest on reserves, I link it to reserve requirements. Both are central bank tools that can affect the money multiplier (whether intentionally or not), in contrast to open-market operations and discounts, which affect the monetary base.

Scott Sumner

Jun 30 2021 at 4:48pm

I do exactly the same.

bill

Jul 1 2021 at 1:42pm

Even today, I think less than 5% of the people know that IOR was zero for the 95 years prior to October 2008.

John Trainor

Jul 1 2021 at 2:05pm

Understanding macroeconomics was a struggle for me as a student in college and then in graduate school. The challenge continues–I teach Advanced Placement Macroeconomics at a small public charter school in Miami, Florida.

I had composed a long comment with reflections on challenges and suggestions about teaching macroeconomics, AP Macro in particular. Mercifully, I managed to delete most of it inadvertently. I would, however, like to convey thanks.

Marginal Revolution University is an outstanding resource for me. Tyler Cowen, Alex Tabarrok and their team produce excellent, clear videos, always with sound economics, that I use often.

For Scott and commenters, this and other conversations on EconLog and Money Illusion are tremendously helpful to me in learning and teaching. I’m particularly pleased to read Jeff Hummel’s and Scott’s comments about your approach to teaching, not least as confirmation for my (similar) approach.

Finally, Scott’s textbook is excellent.

Thanks again,

John

Scott Sumner

Jul 2 2021 at 1:14am

Thanks John, I appreciate those comments.

Comments are closed.