V.1, Entry 35, ALGERIA

ALGERIA

ALGERIA. Since its assimilation with France declared by the decree of Oct. 24, 1870, Algeria should be described as a part of France situated in the north of Africa, and forming the three departments of Oran, Algiers and Constantine.

—GEOGRAPHY. Algeria is the central part of the geographical region which comprises, together with Algeria itself, Morocco on the west and Tunis on the east. It extends from parallel 33° to 37° north latitude, and lies between longitude 6° cast and 5° west, reckoning from the meridian of Paris. The meridian of Paris cuts it into two almost equal parts, in the centre of which is Algiers on the north coast of Africa, at 0° 44′ of east longitude.

—The mountainous region of the Atlas has been called “the isle of the Occident” by Arab geographers. It is a sort of island bounded on the north and west by the ocean; on the north and east by the Mediterranean; on the south by the Sahara, which seems to be the bed of a dried-up sea, extending from Cape Noun and Bajador to the Gulf of Gabès. It forms a distinct geographical system, devoid of apparent connection with other regions of Africa. The desert separates it from Africa, and the sea connects it with Europe. It is, properly speaking, a

minor Africa or a European Africa. Its climate and flora remind one of southern Europe, Andalusia, Sicily and Provence. The chain of the Atlas rising in the west, opposite the Canary islands which belong to its system, stretches northward to Fex, and enters the provinces of Tafilelt and Morocco, where it is 4,000 metres in height, and covered with perpetual snow. Thence it bends to the east; running parallel with the Mediterranean coast to the mountains of Fossato on the confines of Tunis. It stops at the heights of Gabès, where the sandy region commences.

—Two great chains of mountains are to be distinguished in this region, that of the Sahara and the Central chain, and a third range which reaches to the sea. Only one group of the Sahara chain sends its waters to the sea, that of Djebel-Amour on whose northern slope the Shelliff, the largest river of Algiers, has its origin. The Central chain pours its waters, on the south, into the sands where they are lost, and into the basins where they evaporate in summer. On the north its waters enter the sea.

—Algeria has three natural divisions. 1st. The Tell on the north, which is arable. It embraces all the Mediterranean slope between the sea and the Central chain, and in addition certain tracts of the Sahara slope of this chain, such as the country of Batna, Medjana and Hodna, in the province of Constantine. On the east the Tell extends further inland than in the other provinces. The tell contains about 14,000,000 hectares. 2nd. That south of the Central chain, the region of lofty table-lands and the

Chotts, a country of steppes and flats only fit for pastoral life. 3rd. The Sahara which properly speaking only begins south of the Sahara range. On both slopes pasture lands are found during the rainy season. Further on, a forest of date palms may be seen, from time to time, as a green island in a sea of sand. These oases situated on the flats are nourished by rivers which are almost always under ground, and whose waters, brought to the surface through ordinary or artesian wells, render possible the culture of the palm and a certain number of vegetables. In the mountains large hamlets, called

ksours, serve as dwelling places for a settled population, as well as markets and granaries for the pastoral tribes of the country about.

—The climate of the Tell is that of warm temperate regions; it calls to mind southern Europe. On the sea-coast and on the plains, there is no winter, simply a rainy season. The hottest part of the Tell is in the plains of thè west and the valley of the lower Shelliff. In the Tell there is winter only in the mountains, and the interior towns usually situated at high altitudes. Sétif is 1,085 metres above the sea; Médéah, 940; Milianah, 900; Aumale, 850; Tlemcen, 800; Constantine, 650; Mascara, 600. In these towns the summer is hot, and the cold comparatively severe in the winter. Snows prevent terraced roofs. The rainy season commences everywhere in October, at the earliest, and ends completely at the close of April. The yearly average rainfall increases toward the east from Oran to Algiers, Constantine and Tunis. The proportion is approximately 3, 4, 5, 6.

—South of Tell the heat is great in summer, but the winter is cold on the

elevated plateaux. The nights in summer too are cold. In the oases as well as on the flats there is no winter perceptible to the European, and the nights are hot.

—All the agricultural products of France thrive, and all French fruit trees yield well in Algiers. Winter wheat is the indigenous variety. Sicilian flax is cultivated for its seed. The

alfa, a kind of grass which Spain alone exported at one time, and of which cords and mats are made, and in England paper, is exported in large quantities from Oran. The climate has allowed the naturalization in Algeria of the banana and cotton. The

hénna of the south and Mostaganem is sent to the dye works of France. In the torrid basin of the lower Shelliff and the west certain modes of tropical culture are possible, provided irrigation be practiced. When the damming of the Habra is finished, the greatest work of its kind in the world (30,000,000 cubic metres) it is proposed to utilize its water for the cultivation of the sugar cane.

—In addition to the domestic animals of France, we find in Algeria the dromedary used for transporting burdens, for food, for clothing and furniture of the natives. The southern steppes afford pasture to countless flocks of sheep; many of these are sent to France and Spain, and their wool supplies the factory of Roubaix. Algeria is very rich in marbles and minerals. Between Oran and Tlemcen, the mine of transparent onyx so celebrated in antiquity has been rediscovered and is worked. The white marbles of Filfila are of the highest quality. The lack of coal prevents the smelting of iron ore, but it abounds to such a degree that the ore of Souma is sent abroad from Algiers, and at Bona a thousand tons of the magnetic iron of Moktar-el-Adid are shipped each day. At Gar-Rouban, near Morocco, a mine of lead with veins of silver ore, is worked. Zinc can be had in the district of Bona, and there are many beds of copper ore.

—ETHNOLOGY.

Berbers or

Kabyles. Among all the races inhabiting northern Africa, at the present time, the Berbers have been longest in the land. All the conquerors of Africa, Carthaginians, Romans, Vandals, Arabs, Turks and French, have had to struggle with them. The Arab conquest forced them into the mountains where they still remain. Converted to Islamism, at a later period they took a prominent part in the different invasions of Spain by the Mussulmans. To them is attributed the high state of agriculture in Mussulman Spain. Their language belongs to the Semitic type, but differs more from the Arabic than the Hebrew and Syriac. An experienced eye never mistakes a Kabyle for an Arab of pure blood. The Kabyles and Arabs differ in everything,—in language, in physical type, in aptitudes in manners, and institutions. They have nothing in common but religion. In contrast, however, with the Arab the Kabyle is little inclined to religion.

—In the mountains where the population is dense, land is scarce, and living difficult. The laboring Kabyle is rather a gardener and an artisan than an agriculturist. He prepares oil and figs for export, makes powder, arms, tools and household implements, soap, cloth, trinkets and earthenware. He peddles these articles in the Arab districts, and gets in exchange for them cereals which his own mountains do not produce in sufficient quantity. He goes to the villages and plains, to work for the Arab agriculturist, or the European manufacturer. He lives in a house and not under a tent or a

gourbis like the Arab, who is always a half nomad. The Kabyle villages built on the crests of hills are little fortresses. The women are not veiled, and when guests are entertained they are not sent away. The land belongs to the family, not to the tribe.

—Each Kabyle tribe is a little democratic republic, with an assembly,

djemmáa, composed of all men able to bear arms. The

djemmáa makes the laws, decides cases, regulates the administration, elects a chief

amin, who is charged with carrying out its decisions; it concludes alliances between tribes, and decides on peace and war. The Kabyle tribes arrange themselves in confederations like the ancient leagues of the Grisons. Personal rivalries almost always separate them into two parties called

sofs. Each one of these allies itself to the

sofs of the neighboring tribes.

—Hospitality is regulated by law, and is exercised in turns; it is not considered as a religious but a public duty. The Kabyles have an institution of international or rather inter-tribal law peculiar to themselves, the

anaya. It consists in the protection afforded an individual either by a private person or by a tribe. A stranger, and even an enemy, who has obtained the

anaya, is held inviolable, under pain of death. War breaks out between tribes frequently because the

anaya has not been respected. Peace is concluded between tribes by the exchange of pledges, the withdrawal or giving up of which is a declaration of war.

—The authority of France is exercised in Kabylia only in the following manner: it reserves to itself the exercise of the police power, criminal and correctional matters; it confirms the

amin elected by the tribe, has agents called

amin-el-oumena, who act for it as intermediaries with the

amins of the several villages; it collects a poll tax in accordance with a list of names drawn up by the

djemmáa. In this list the Kabyles are ranged in four categories, according to their fortunes. Of these the last is exempt from taxation; in the other three the tax varies, but is the same for all members of the same class. It was sought to introduce the office of cadi in civil cases, but the Kabyles wished to judge themselves by their own laws in general assemblies. They admit neither cadis nor the authority of the law of Islam. Justice is, in their eyes, a social question to be regulated by men, and a matter of religion decided in a sovereign manner by the Koran. These institutions are preserved intact only in Great Kabylia.

—In Algeria the Berbers are called Kabyles, which, in their language, means confederates. In Aurès alone they are called

Chaouia. The population of the oases

and the

ksours of the Sahara is mainly of Berber origin, and has preserved in part the communal institutions of the Kabyles. The Touaregs in the depths of the Sahara and half way to Soudan are of the pure Berber race.

—

Arabs. The Arab tribes lead a pastoral life in the south, and are agriculturists in the Tell. There are some who change their habitations and mode of life according to the season of the year. Each tribe forms a kind of little nation with its territory, chiefs and history. The tribe is scarcely more than one family grown to the maximum of extension which in Mohammedan countries is great.

—The Mussulman family has more affinities than the Christian. By polygamy, by adoption, through foster parents more numerous ties are formed than with us, and even divorce does not break them up completely, if children have been born of the marriage. Moreover the parents are not separated by material interests, for their landed property remains undivided (land

melk), and they live together on the family estate. The life of relations in common and innumerable alliances determine the formation of a natural group, the tribe, which is almost entirely made up of relatives or allies. The fractions of the tribe are called, according to their importance,

Ferka, Khoms or

Douar. The chiefs of families or of tents, are the representatives of the tribe, and they make up its

djemmáa which is its national assembly. If there is a family more ancient or more powerful than the rest, it is the natural head of the tribe.

—The Arab tribal government is, therefore, patriarchal and aristocratic. In Arab countries there are three kinds of nobility, the

chorfa, nobles by origin through descent from the daughter or uncle of the prophet; the

djouad or military nobility; the

marabouts, descendants of the saints of Islam. In certain tribes all the men lay claim to nobility, others are composed of

marabouts alone.

—The noble is not jealous, and his authority is not called in question. He is the honor of his tribe. This social organization gives a common interest to the tribe, and causes its members to render mutual assistance in time of need and against the stranger. Such was the Arab tribe before conquest changed its character.

—The conqueror, Turk or Frenchman, has been frequently obliged, in the interests of his own power, to deprive the natural chief of authority and confer it on an inferior and sometimes a stranger. This chief has become a functionary in the service of France, charged with subjecting the tribe to French policy; he is imposed upon it and supported against it by the power of France. He often lacks authority and has tradition against him. If he is guilty of exactions the tribe must endure them, or go to war with France. Complaints against a chief whom they can not depose are regarded as opposition to French dominion, and are generally rejected. In a word, the imposed functionary often takes the place of the natural chief.

—Moreover the prohibition by France of inter-tribal wars and the personal security afforded by the French police have made it unnecessary for the Arab nobility to uphold and protect, for purposes of self-defense, numerous clients who in return used to fight for them.

—The exportation of wheat, which began since the conquest, has resulted in decreasing the reserve stock of cereals Let a bad year come, and the

khammès, who tills for the fifth part of the produce, no longer finds open to him the corn pits of his master which in old times were filled with the surplus of fruitful years. This grain has been sold, its value has been already spent, or if the master has hid the grain away in the ground, he is less disposed to lend money to the

khammès than he was formerly to furnish wheat at nominal prices. In case of scarcity the

khammès dies of hunger, as in 1867.

—The rule of conquerors has deprived the government of its patriarchal character, the security established by the French has relaxed the bonds of mutual interest which united the aristocracy to its clients. The grain trade has interfered with the assistance given by the rich to the poor in time of scarcity. A social and political revolution is going on through the force of circumstances, and independent of the will of man. This revolution will bring about dislocation of the tribe, the destruction of traditional relations between the nobility and their clients, and, consequently, the destruction of aristocratic power.

—

Moors. These are Mussulmans who do not belong to any tribe, and who inhabit the cities or their outskirts. They are called

hadri or citizens. A few of them are descendants of the Moors expelled from Spain, and the majority are Arabs or sons of Arabs who have left their tribes in order to become citizens. A few are landed proprietors. The chief means of subsistence for the others is commerce, principally the manufacture of articles used by the tribes—shoes, saddles, implements, etc. In Tlemcen and Constantine whole streets are lined with the shops of Mussulman artisans.

—The Moorish population is in a state of decadence. Living has become more expensive, and provisions and rents have risen enormously since the conquest. Processes of labor have not improved among them. The native consumers of the outlying districts have been replaced by Europeans. For the artisan of the towns the temptations to expense are greater than formerly. The result is that families once rich, but destitute of foresight, sold their farms, (

haouch), then their country houses, later their houses in town, and at last pawned the pearls and jewelry of the women, in Algiers at the pawnbrokers, and elsewhere to Jews. These pledges are rarely redeemed. The Moorish population is sinking little by little and will never rise again. At Constantine, Tlemcen and other towns the artisan holds out yet, but even now, in the case of certain articles used by the natives, he has to struggle against the competition of European factories; perhaps he will be driven from the market in the case of other articles.

—

Kouloughlis. These are descendants of the children of Turkish fathers and Arab mothers. They

are found especially in the towns which were the centres of Turkish domination. They retain the overbearing pride of the conqueror toward a vanquished race. At Tlemcen they are equal in number to the

hadri and are always in rivalry with them, which causes difficulties to the French administration.

—The Kouloughlis, like the Turks, follow the

Hanefi rite, while the Arabs observe the

Maleki. These are two of the four rites equally recognized as orthodox by the Sunnite Mussulmans. These two rites differ by a few legal provisions, concerned particularly about the inheritance of women and the forms of prayer. At Algiers and Constantine each rite has its mosques, its ministers of worship and its

cadi—

Mozabites or Beni-Mzab, merchants and artisans, temporary emigrants from their oases situated at 1° east long and 33° lat. They are Abadites, partisans of the assassins of Ali, and equally regarded as heretics by the Sunnites and Chilites. Their

imans or sovereigns had Tiaret as their capital at the epoch of Mussulman conquest. At present their iman resides at Muscat. They are puritans of great probity, and look down on everything not Mozabite. Laborious, industrious, economical, they make large profits in business. A Mozabite who emigrates is forbidden to take with him his wife, or his children of a tender age, to marry a foreign woman, to visit women of improper life or to neglect the practice of his religion. He is obliged to render an account of his commercial transactions to the federal council. Emigrants in the same village hold meetings for prayer and the censorship of private life. Corporal punishment is inflicted during the meetings. But if a Mozabite has met with reverses in business, and it is shown by the assembly that he was not at fault, his co-religionists make good his losses.

—

Native Jews. Their mother tongue is the Arabic, but a certain number have learned French. Among them are found rich merchants, wholesale and retail, who lend money (in Algiers there is no legal maximum of interest). Many of them are shopkeepers, a certain number artisans, factotums of great Arab lords, hawkers, who compete sharply with the Kabyles among the Arab tribes, traveling jewelers, who manufacture on the spot and deliver in jewelry the same weight as the Arabs give them in coin. Active, industrious, economical, and selling at the highest figure, they succeed as a rule. The French conquest has freed them from exactions and humiliations. It is only in the extreme south under the rule of great Arab chiefs, who are sometimes vassals and sometimes enemies of the French, that the Jews are still obliged to remove their shoes in passing before a mosque, not to ride on horseback, and to give bonds whenever they absent themselves. A decree issued Oct. 24, 1870, by the assembly at Tours, granted to natives the rights of French citizens. They are now electors and jurors.

—

Negroes. Brought from the Soudan as slaves. The trade in negroes, by way of the Sahara, was continued for a long time after its prohibition by the republic in 1848. They are not numerous, and tend to disappear, either by extinction or by mingling with other races. Some of them are like Arabs of dark complexion.

—

Europeans. The Spaniards are settled mostly in the provinces of the west and centre, the Italians and Maltese in the east and centre. The French are most numerous in the province of Algiers. The census of 1866 gives a total of 2,912,630 inhabitants classified as follows. Mussulmans, 2,652,072; Native Jews, 33,952; Europeans, 226,000. Official statistics do not distinguish the Kabyles from the Arabs.

—The European population, in which the army is not included, is made up of two elements: the inmates of the hospitals, lyceums, schools, orphan asylums, seminaries, convents and prisons, 8,616; the fixed population, 217,990. The figures for each nationality have been determined only in the case of the fixed population. They are reckoned as follows: 122,119 French; 58,510 Spaniards; 16,655 Italians; 10,627 Anglo-Maltese; 5,436 Germans; 4,643 of other nationalities. Since the census of 1866, the famine which desolated the Mussulman territory in 1867-8 carried off perhaps 500,000 Mussulmans. Certain tribes have been almost destroyed and certain regions depopulated. In the same period the drought which prevailed in Spain, and later the exportation of

alfa, brought into the west a great number of Spaniards.

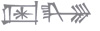

—HISTORY. This is conjectural up to the foundation of Carthage, 850 B. C. This city became mistress of northern Africa, which furnished its mercenary armies with their famous Numidian cavalry. In 250 B. C. the Romans began to struggle with the Carthaginians for northern Africa. In 146 they destroyed Carthage. In 646 A. D. the Arabs showed themselves in Tunis for the first time. The Goths were the masters of Tingitane. In 670, the fiftieth year of the Hegira, Okba founded in the southeast of Tunis, Kairouan, the Mussulman metropolis of the province of Africa.

—After the fall of the Almohades, northern Africa was in a state of political decomposition, when two corsairs, the brothers, Baba-Aroudj and Kheir-ed-Din, established Turkish dominion by taking Djidjelli from the Genoese (1504), Shershell and Algiers from the Arabs (1515) and the rocks in front of Algiers from the Spaniards in 1530. By connecting these rocks with each other and with the land by a dike, Kheir-ed-Din created the port of Algiers. The successors of the two corsairs completed the conquest of Algiers.

—The Turkish government, in Algiers, was a piracy on sea against Christians and on land against Arabs. Its instruments were: 1st. Janissaries recruited in Turkey; 2nd. Kouloughlis, descendants of Turkish fathers and Arab mothers; 3rd. Arab tribes known under the generic name of Maghzem, and who were settled from east to west along the strategic line north of the Central chain of mountains. These tribes, exempt from tribute and occupying their own land granted by the Turks, were bound to lend physical aid in collecting taxes, and against such tribes as might rebel. They also had their share

of the spoils. In general the Turks left the Arabs to their own devices, provided only that they paid tribute and yielded to the exactions of the conquerors. The Kabyles, protected by their mountains, preserved their independence almost everywhere.

—

French Conquest. It will be remembered that in 1827, in consequence of a fruitless claim addressed to the French government by the dey, Hassein-ben-Hassem, on account of grain furnished in 1796, by the Jew Bacri, a debtor of the dey, the latter struck the French consul, M. Deval, with his fan. Algiers was blockaded directly, and all reparation being refused, a French army landed June 14, 1830, at Sidi-Ferruch and entered Algiers in triumph July 5. From that day is dated the abolition of piracy and the foundation of African France.

—Algiers taken, it remained to conquer Algeria. Oran was occupied for good in 1831, Bona in 1832, the ports of Arzew and Mostaganem in 1833, when Bougie also was taken. Tlemcen, occupied in 1836, was held by Cavaignac for seven months, at the end of which time General Bugeaud came to relieve the place. Clausel failed the same year before Constantine which was taken Oct. 13, 1837, by General Vallée after the death of General Damremont. Djidjelli was captured in 1839, Shershell, Médéa and Miliana in 1840. But it was only in 1841 on the accession of Gen. Bugeaud to the office of governor general, that the great African war commenced.

—Abd-el-Khader, saluted emir in 1832 by the Hashems south of Mascara, had been recognized as sovereign in a treaty of peace concluded by Gen. Desmichels in 1834. After breaking this treaty he defeated Gen. Trezel at Macta. It was a rout, and the enemy massacred the French wounded. Clausel, the same year, avenged this defeat by taking and destroying Mascara, the capital of the emir. The following year Bugeaud defeated Abd-el-Khader at Shiffa. Unfortunately he concluded with him, in 1837, the famous treaty of Tafna which gave up to the emir half of Algeria.

—The passage of the Iron Gates in 1839 by Marshal Vallée and the Duke of Orleans, was the occasion of a rupture with Abd-el-Khader. By the treaty of Tafna, the frontier line of the east, settled upon, was the road from Algiers to Constantine which no longer exists. The emir pretended that that line had been crossed by the French, and declared war. Marshal Vallée allowed the Arabs to invade and devastate Mitidja. They arrived in the neighborhood (

sahel) of Algiers and their horsemen came to the sea-coast within cannon shot of the French forts. In 1840 the war became general in the centre and west. Gen. Bugeaud, appointed governor general in 1841, inaugurated a new system of war that was to bring about the ruin of Abd-el-Khader.

—The French base of operations, till then the sea, was transferred to the centre of the Tell between the sea and the mountain range which separates the Tell from the elevated plateaux. Military forces were firmly established from east to west at all points which commanded this strategic line. Thence light expeditionary corps were dispatched continually, operating near their basis, and forming a net which covered the country. At the same time Abd-el-Khader was isolated from his allies of the south by the erection of a chain of small forts which guarded the passes leading to the lofty plateaux of the Tell, of Oran and Algiers. When the net was extended the campaign began. The work lasted six years. Abd-el-Khader’s permanent establishment at Boghar, at Taza, at Tackdemt, at Goudjela, were destroyed. All the tribes of the Tell, one after another, saw the French columns enter their territory, and learned by experience that neither the mountains of the Ouarensenis nor those of Dahra and Great Kabylia could protect them against the arms of France. The attacks made in the south by Yousouf, at Djebel-Amour, by Cavaignac, Renault and Géry among the Oulad-Sidi-Chikh, by Marey-Monge at Laghouat, deprived the enemy of every chance of succor from the Sahara populations. Abd-el-Khader still relied on the Moroccans, but these were repulsed in May and June, 1844, by Lamoricière and Bedeau, and finally conquered at Isly, Aug. 14, by Marshal Bugeaud.

—Nevertheless Abd-el-Khader could not be captured. If, during his absence in 1843, the Due d’Aumale deprived him at Taguin of his head-quarters, that great nomad town, the wandering capital of the emir, the latter, by a prodigious march executed the same year, over one-half of Algeria, eluded five army corps who were watching his passage. He came again in 1846 to Great Kabylia, which refused to rise up in his behalf. Having taken refuge in Morocco, he was afraid of being delivered up to France by the sultan of Fez. After the submission of his two lieutenants, Ben-Salim and Bel-Kacem, as well as Bou-Maja soon after, he surrendered to Gen. Lamoricière Dec. 23. 1847, at Sidi-Brahim, where two years before he had carried off Col. Montagnac and his column. The great African war came to an end with the downfall of the redoubtable chieftain. It only remained to finish the conquest and repress uprisings.

—In 1849, the taking of the oasis of Zaatcha after a siege of 52 days, the occupation of Bousada in 1852, the capture of Laghouat and the founding of Djelfa; in 1853, the creation of Géryville assured the French supremacy in the south. Great Kabylia, roused to rebellion from 1851 to 1853 by the cherif Bon-Barla, was finally subdued in 1857, under the government of marshal Randon. The posts of Tizi-Ouzon (1851), of Dra-el-Mizan (1855), and fort Napoleon (1857), now fort Republic, guarantees French rule in the interior of Great Kabylia.

—In 1859 the fruitless expedition of Gen. Martimprey, in Morocco, cost the lives of many thousand men from cholera. In 1864 a quarrel with the chiefs of Oulad-Sidi-Shikh, a tribe of Marabouts in the extreme south, whose religious influence is very great, brought about a war with the French of long duration. It caused an insurrection, the same year, in the Tell of Oran and in the south of the province of Algiers.

—It was hoped that the war with Prussia would be finished without an insurrection in

Algeria, though there was not a single regiment of French regulars in the country. There were merely native regiments and

gardes mobiles without military training and not feared by the Arabs. An order for the mobilization of the

spahis to France led to an uprising Jan. 23, 1871. At Ain Guettar, on the frontiers of Tunis, the neighboring tribes joined with the

spahis. Later, when peace was concluded, Mokhrani, grand chief of Medjana, who owed nearly a million at Constantine, rose up in his turn and carried with him all Great Kabylia. Soon the whole province of the east was in arms. The revolt was completely crushed only in November, 1871.

—French supremacy in Algeria is secured by three chains of posts, each extending from the boundary of Morocco to that of Tunis, the maritime line, the central, and the frontier line of the Tell. South of this last advance posts have been established in the Sahara.

—On the seaboard, from west to east, are the ports of Nemours, Mers-el-Kébir, Oran, Arzem, Mostaganem, Tenès, Shershell, Algiers, Dellys, Bouzie, Djidjelli, Collo, Stora, Phillippeville, Bona, and Calle. There are two fine natural harbors, Mers-el-Kébir and Bouzie; an excellent natural harbor, Arzem, which has been improved; two other natural harbors, Djidjelli and Collo, the latter of which is in good condition; the great harbor of Algiers, created, like that of Cherbourg, by means of dikes; that of Bona, less extensive, but which French engineers have made better than Algiers. The harbor of Oran was created by means of dikes. The harbor of Phillippeville has been greatly improved. There are no other real harbors, but merely foreign roadsteads, at other points on the coast.

—The central line of the Tell is the great strategic line of Algeria. The power that controls it is master of the country. The French hold it by virtue of a chain of settlements nearly all of which are situated at the points formerly occupied by the Turks and the Romans. On a line from west to east, the settlements are Lalla Maghnia, Tlemcen, and Bel-Abbes, the strategic centre of the province of Oran; Mascara, Relizane, Orléansville, Miliana, Médéa, Aumale, Bordj-bou-Arreridj, Sétif, Constantine, Guelma, and Souk-Ahras. The Arab invasions followed this line, from east to west, thence fell back to the northward and southward. The Romans, the Turks, and Marshal Bugeaud, conquered Algeria by occupying the central line as a basis of operations, while the Spaniards failed because they occupied the coast only.

—The frontier posts in the province of the Tell bar the entrance against invasions from the southward. These posts, in the mountainous districts, guard the passes which give ingress to the Tell; and on the plains they occupy the points which command the great roads of the south. From west to east, the posts are Sebdon, El-Hacaïba, Daïa, Saïda, Frenda, Tiaret, Tenièt-el-Haad, Boghar, which covers the entrance into the Tell through the valley of the Chelif; and Batua and Tebessa. These posts close the Tell against invasions by the herders from the south, while they open it to trade with them. Through these posts the herders come to barter the dates of the oasis and the wool of their flocks, for the cereals of the Tell which afford food to the south.

—On the south of the frontier of the Tell and on the road to the Sahara, the French permanently occupy Djelfa and Boucaada; and within the Sahara they occupy the oasis of Laghouat and Biskra, together with the post of Géryville. This occupation is intended to protect and confine, by crowding them between the northern posts and the frontier of the Tell, the pastoral tribes which their geographical position renders dependent on the Tell for their natural market.

—GOVERNMENT. The character of the government of Algeria is one of instability, and its normal condition change of form. The following are its principal phases of transformation: 1st. A provisory organization (1830-34). Authority exercised by the commander-in-chief of the army of occupation, who had under his immediate control a council called successively government commission, committee, administrative commission, and administrative council of the regency. Marshal Clausel confided the presidency of the committee and the territorial administration to the military

intendant. The duke of Rovigo instituted a civil administration.

—2nd. Governor generalship. The ordinance of July 22, 1834, created a governor general of the French possessions in the north of Africa. The ordinance of April 15, 1845, changed this title to governor general of Algeria, divided Africa into three provinces, and each of these into a civil, an Arab and a mixed territory. It instituted a general mode of administration of civil affairs, an upper council, and a council of claims.

—In 1847 the ordinance of Sept. 1 inaugurated decentralization by appointing in each province a director of civil affairs and a council of administration. The progressive assimilation to France was commenced by the republic of 1848, which suppressed, on Dec. 9, the general administration of civil affairs, and created a department in each province with a prefect and a council of prefecture. Algeria had been in the jurisdiction of the ministry of war, where there had been created in 1837 a department under the name of division of Algiers, and later a department of the direction of affairs of Algeria, charged with the political and civil affairs, and besides a committee of consultation to examine all proposed laws, ordinances or regulations, as well as all affairs referred to it by the minister.

—3rd. Ministry of Algeria and the colonies, (decree of June 24, 1858). The governor general was replaced by a minister residing in Paris. The council of government was suppressed. Councils general were instituted. The jurisdiction of prefects in civil affairs and of generals of division in military affairs was amplified. Under the name of upper commandant of the land and sea forces, a general officer is made chief of the army of Africa.

—4th. Re-establishment of the governor generalship, (decrees of Nov. 24, and Dec 10, 1860).

The ministry of Algeria and the colonies was suppressed. A governor general is entrusted with the command of the land and sea forces, the government and administration of Algeria. This officer is tantamount to chief of the state. He prepares the budget to be approved and presented to the chambers by the minister of war, as an addition to the military budget, and orders what grants shall be allowed. He prepares the decrees which the minister of war submits to the chief of the state for his signature and countersign. He appoints to certain offices. But the administration of justice, and French public instruction, religious worship, the custom and postal service, and the treasury, are each under the jurisdiction of a special ministry.

—Under the authority of the governor general the administration of Algeria is divided between two high functionaries, a sub-governor and a director of civil affairs, independent of each other. The sub-governor, in addition to his duties as chief of staff of the army of Africa, governs the military territory through three generals of division, with generals of brigade or colonels commanding subdivisions, and chief commanders of circuits. Each of these officers continues to keep under his orders one of those bureaus celebrated under the generic name of Arab bureaus, and which are named according to their degree, descending from the sub-governor to the commander of a circuit.

—The director of civil affairs administers the civil territory through three prefects, with sub-prefects and civil commissioners. These unite in themselves in places where the commune has not yet been organized, the functions of mayor, sub-prefect, and, at certain points, those of justice of the peace.

—To sum up, a superior council, of which six delegates from three general councils form a part, prepares the project of the budget for the general government and the assessment of taxes. A consulting council gives its advice on all affairs placed before it by the governor.

—In this organization the civil and the military authority were independent of each other, and each free on its own territory. Marshal Pélissier used to say, “I am neither civil nor military governor; I am governor general.”

—By the decree of July 7, 1864, the civil was everywhere subordinated to the military authority. The generals commanding the three divisions took the title of commanders of provinces. The prefects were placed under their authority. received their instructions from them and addressed their reports to them. Algeria was subjected to a purely military government, which had, under its orders, a certain number of civil agents. Nevertheless, two decrees of 1866 and 1870 made the municipal and general councils elective.

—5th. A civil governor generalship, (law of Oct. 24, 1870). By this decree the delegation of Tours founded in principle the civil government such as it still exists, at least in form.

—The civil governor general retains the political, military and administrative powers of the military governor. He administers the former civil territory through a secretary general and three prefects, and the military territory through a chief commandant of the land and sea forces, who has under his orders as administrators of these territories, three generals of division, with commandants of subdivisions and circuits.

—To sum up, a superior council of government and a consulting committee are appointed, the first with more elective members than formerly, the second with some elective members, which was not the case in the council of the previous government.

—During the war with Germany, this government, as a whole, existed only on paper. The councils-general of Algeria had been dissolved simultaneously with those of France; the superior council could not be brought together for lack of members. Besides, the delegation of Tours, on account of representations from Algeria, had, in November, decided in principle on the abolition of the governor generalship, with the attendant offices which had been established or retained by it in October. Algeria was to be assimilated to France and its local institutions were to disappear. A decree had already deprived the chief commandant of the army and navy of authority over the tribes of the military territory, and another decree suppressed the special budget of Algeria by distributing it among the budgets of the different ministries. Of the institutions founded by the decree of Oct. 24 some could not come into existence, others existed only temporarily, and deprived of all assistance from the councils-general and the superior council could not come into regular operation.

—The government of M. Thiers retained the governor generalship and the superior council; it abolished

de facto the office of commander of the army and navy and re-established the special budget of Algeria. Algeria has retained the six representatives in the national assembly accorded it by the delegation of Tours. Natives appointed by the government form a part of the general councils, in which the great majority are Frenchmen, and are elected. The natives have a deliberative voice. This has given rise to formal protests in the three councils.

—It would be difficult to define and classify the actual government of Algeria (1872.) Let it suffice to state that it bears the name of civil government and has as chief a naval officer who governs the regular military territory, that is, almost all of Algeria, through officers of the army.

—TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION. Before the revolution of September it had as basis the division of each province into two territories, one civil which constituted the department and was governed by a prefect, the other military and governed by the general commanding the military division. The decree of Oct. 24, 1870, has in principle suppressed the military, but in fact it has left the administration of the government to the officers who exercised it before without subjecting them to the prefect. The original military territory is yet (1872) in practice outside the authority of prefects. Officers manage it, under the direct

authority of the civil governor general. The original civil territory forms but a diminutive part of Algeria. The administration of the country, as we see, has remained military in fact, although the governor bears the title of civil governor, and the designation ‘military territory’ no longer exists. The situation is undefined. There is no correspondence between things as they exist and the words which describe them. Algeria is in a state of transition between the military régime existing in fact and the civil régime which exists only in name. It is intended to increase the number of Algerian departments. The councils-general and municipal have the same attributes as in France. The councils-general have native members appointed by the government. The municipal councils are made up of members native and foreign, both elected, like the French council. There are no councils of the

arrondissements.

—The Arab and Kabyle tribes of the original military territory are governed as formerly by military commandants who have Arab bureaus at their disposal. The title of these French agents has changed, but their powers have remained the same. They continue, among the tribes, to take charge of politics, the administration, the legal police, the assessment of taxes. They have always native chiefs at command called

caïds, who, each in his own tribe, see their orders executed and collect the taxes.

—FINANCE. The Arab taxation has retained its former character. 1st.

Achour, or tithes of grain, the taxable unit being the plow, (

djebda), that is to say, the area which it is possible to cultivate annually with one plow. Every year the tax on a

plow is determined by the amount of the crop. 2nd. The

zekkat, tax on flocks and herds; the rate is fixed annually. 3rd. The

hockor, or rent of lands,

azel, belonging to the state and worked on a permanent lease by the natives. 4th. The

lezma or obligation. It is collected in different ways. 5th. In the south, various taxes on trade, on the purchase of grain, on date palms.

—One-tenth of the Arab tax goes to the native chiefs who collect it, four-tenths of the remainder goes to the state, and six-tenths to the departmental budget.

—There has been long under consideration a project to replace the

achour and

zekkat, the tax on grain and cattle, by a land tax. Lands belonging to Europeans are not taxed, but registration dues, stamp dues, the customs, licenses, indirect taxes, postal and telegraphic charges, come almost exclusively upon Europeans. The budget of the governor generalship of Algeria furnishes the following figures:

| 1865, receipts… | 17,713,804 francs. |

| 1865, expenses… | 25,350,000 “ |

| 1870, receipts… | 16,500,000 “ |

| 1870, expenses… | 14,616,000 “ |

| 1872, receipts… | 17,043,000 “ |

| 1872, expenses… | 22,615,014 “ |

The following are the chief items in the budget of 1872:

| Registration, stamps, domains and forests, | 5,647,500 francs. |

| Customs… | 2,351,000 “ |

| Income from various sources… | 7,421,500 “ |

| Four-sixths of the Arab tax accruing to gov… | 4,605,000 “ |

| Post office… | 1,000,000 “ |

| Receipts from various sources of which 535,000 francs are from the telegraph… | 623,000 “ |

| Central administration… | 514,500 francs. |

| Departmental administration… | 969,660 “ |

| Prisons… | 973,200 “ |

| Telegraphic service… | 1,041,700 “ |

| Administration and management of Arab tribes… | 1,586,390 “ |

| Financial service… | 3,122,762 “ |

| Maritime and military service… | 500,000 “ |

| Colonization… | 1,325,600 “ |

| Topography and land registers… | 1,035,500 “ |

The budget commission of 1872 estimates that by transferring the collection of the Arab taxes which, on the average, yield ten millions, from native to French financial agents, the product of these taxes would be perhaps doubled, while the burdens of the Arab tax payer would be at the same time decreased.

—Maritime duties, imposed on the frontier and collected by the custom house for the benefit of Algeria, yield on an average four millions net. Of this, four-fifths, distributed according to the number of the population,

*6 go to the municipal budgets, the rest to the departmental budgets, which are mainly supplied by the six-tenths of the Arab tax which the state has surrendered to them.

—The administration of justice in the case of the Europeans is the same as in France. The natives remain, so far as the civil law is concerned, under the law of Islam; but crimes and misdemeanors committed by Mussulmans are punished according to the French law. Civil cases are judged in Kabylia by the djemmâa, everywhere else by the

cadis. Councils called

Medjelès may revise the judgment of the

cadis, but an appeal, properly speaking, is only made to

the court of appeal at Algiers, and tribunals of the first resort at Oran and Constantine to which are attached, for this purpose, Mussulman assessors. Imperial legislation has forbidden appeal in questions of state and of marriage. It does not permit a case to come directly from the

cadis to a French judge unless with the consent of both parties. Complaints are raised against these two regulations and against the institution of the

Medjelès.

—RELIGIONS. To the three religions in France, where ministers are paid by the state Mohammedanism is added in Algeria. The government has appropriated the estates of the mosques, the property which before the conquest contributed to the support of public instruction, charity and pilgrimages to Mecca.

—Algeria has an archbishop and two bishops. There is a Protestant and a Jewish consistory in each province.

—PUBLIC INSTRUCTION. The academy of Algiers embraces three departments. Its rector is aided by two inspectors. There is a lyceum at Algiers and communal colleges at Oran, Constantine, Bona and Phillippeville, and a secondary school of medicine at Algiers. In 1870 the municipal council withdrew everywhere their aid from clerical schools. The communal are lay schools.

—MEANS OF COMMUNICATION. Algeria had neither roads nor bridges; many of both have been constructed, but the military government has neglected to build a road from Constantine to Algiers. The more important half of Algiers is connected with the centre of administration only by sea, and Constantine is in more frequent connection with Marseilles and even with Paris than with Algiers. Neither is there a road between Bona and Constantine. On the other hand, roads have been built along lines which are little frequented (1872).

—The railroad from Algiers to Oran unites the east with the centre of Algeria. Constantine is put in communication with the sea by the Phillippeville railroad.

—COMMERCE. The principal articles of exportation are winter wheat, wool, and sheep, which the steppes of the south produce in almost unlimited numbers, tobacco, oil, alfa, oranges, mineral ores. Algeria imports textile fabrics, iron, sugar, coffee, soap, spirits, etc.