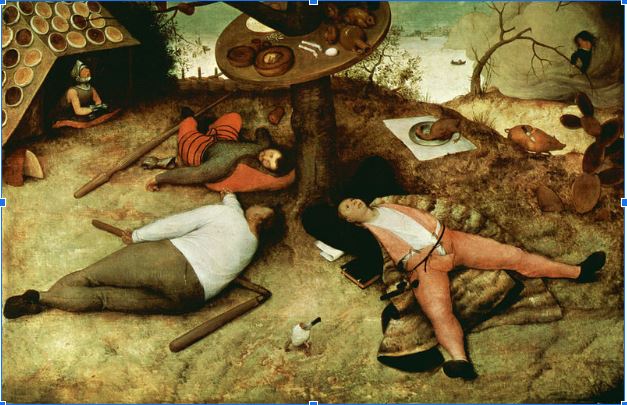

This week I’m heading to Arizona State University to give a talk that explores, among other things, medieval poems about the imaginary Land of Cockaigne and the way they tie in to the way we think about urban and rural labor today. So it was with no small measure of delight that I came across this piece by Matthew H. Birkhold about “The Myth of Blubber Town” at the eccentric and wonderful website, Public Domain Review.

Unlike the imaginary Land of Cockaigne, which is famed in medieval legend as a land where no one needs to work–chickens fly through the air, already roasted and roofs are tiled with pastries–Blubber Town is a legend built on work. There was a real Dutch whaling station in the Arctic called Smeerenburg, where whalers processed blubber for shipping back to the mainland. Current estimates state that no more than 200 men, and no women, stayed at Smeerenburg at one time, and that there were only nineteen or fewer buildings. It was an outpost.

But something about Smeerenburg inspired the same dreams of plenty that spurred the invention of the Land of Cockaigne. From the bare bones reality of Smeerenburg, explorers and scientists created a fantasy of a town of thousands of people, full of shops, pubs, dance halls, and–in some accounts–even a brothel. In a nod to the Land of Cockaigne that I suspect may not be accidental, this fantasy version of Smeerenburg is famed for its bakeries as well. While pies aren’t used as roof tiles, there is so much bread produced in Smeerenburg that the bakers blow a horn every morning to tell the sailors that fresh bread is coming out of the oven.

Birkhold suggests several possible reasons for the out sized legend that attached itself to Smeerenburg. It could be the result of bad history done by lazy historians, a bit of advertising by whalers, a mistaken notion that the lucrative 19th century whaling industry had been as lucrative since its beginnings, or possibly–like the Land of Cockaigne–a bit of wishful thinking on the part of sailors who had an exhausting, grimy, and lonely job.

Don Boudreaux observes in his discussion of a “Quote of the Day” from The Rise of Silas Lapham, that “any value that any human attaches to, or perceives in, the natural environment is necessarily the product of his or her own mind and judgment.” The world is worth what we make of it, with our actions, our choices, and our minds. The medieval workers and the 17th century whalers who looked at the scarcity and grueling labor that ruled the worlds that they inhabited, produced visions of wealth and surplus that–to them–seemed possible only in their wildest imaginings.

But the joy of human history and progress is that as our clever and often very practical ideas about improving humanity’s condition all get tested against each other under the right institutions, we slowly discover ways of making our wildest imaginings come true.

Today, while travelers still can’t get to Cockaigne, they can take a luxury cruise to Smeerenburg on a ship with crystal chandeliers, bars, saunas, and–I’m willing to wager–plenty of freshly baked bread.

Land of Cockaigne, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1567

Comments are closed.