Price Discrimination and the Future of Movies

By Adam Martin

On September 4, Disney released Mulan on its Disney+ streaming service. Mulan’s release was delayed because of COVID-19. For about $30, depending on what country they are in, Disney+ subscribers purchase early “Premier Access'” to the movie before it becomes available to all subscribers. In some countries, including China and others that do not have (legal) access to Disney+, it will still play in theaters.

All eyes in Hollywood are on this move. A few movies have been released straight to video on demand or after a short theatrical run, including Trolls: World Tour and The Invisible Man. But this is the first major blockbuster going straight to streaming that had the potential to be a billion-dollar movie. It’s hard not to see this as a test for other big films like Black Widow. This plan could completely change how movies are distributed going forward. Economics alone cannot tell us whether Disney’s plan will pay off, but it can tell us something about what it will take to succeed. The key concept I want to focus on is price discrimination.

Nerdies and Normies

Imagine two types of consumers: Nerdies and Normies. Nerdies are particular. They like what they like, and they are less willing to accept substitutes for those goods. They like Coke, not Pepsi. Marvel, not DC. And whiskey, not vodka. Normies are more laid back. They care less about particulars. Soda is soda, comics are comics, and booze is booze. In real life, most of us are Nerdy about some things and Normie about most others. I’m a Normie about clothes, but very Nerdy about movies. Others might be the opposite.

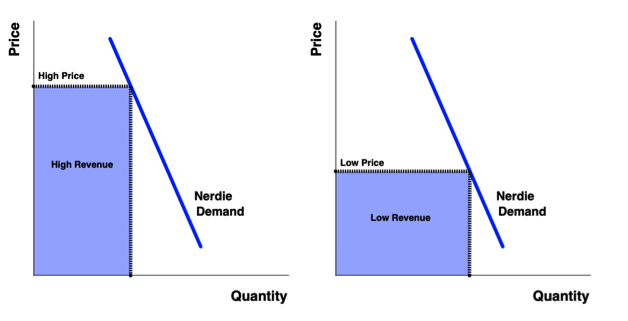

Nerdies and Normies react very differently to differences in price. Let’s take each in turn. The demand curve that Nerdies have for the things they nerd out about might look like the ones in Figure 1. They have what economists call relatively inelastic demand. At a high price, Nerdies are still willing to shell out to get the good. At a low price, they buy more, but not a lot more. If a bar doubles the price of whiskey, Nerdies still won’t switch to gin. Sellers can charge a high price per unit without scaring off the Nerdies, so (all things equal) they make more money selling to them at a high price.

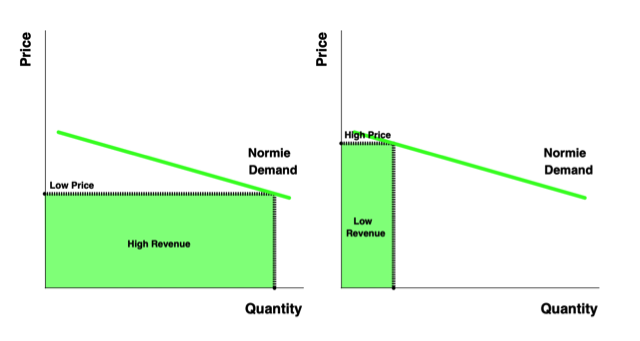

Normies are the opposite. Normie demand curves are shown in Figure 2. They have what economists would call relatively elastic demand. At a high price, Normies just buy other goods. But at a low price, they massively increase their purchases. If Pepsi goes on sale for 10% less than Coke, they switch to Pepsi, because soda is soda. Sellers can bring a lot more Normies into the market by offering goods cheap, so (all things equal) they make more money selling to them at a low price.

One of the problems many businesses confront is figuring out how many of their customers are Nerdies and how many are Normies. Without that information, it is hard to settle on a pricing strategy. Do you make your money offering a select product to Nerdies or selling in volume to Normies?

Why not both?

Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is when a business sells the same (or extremely similar) products to different consumers at different prices. It doesn’t take a lot of math to show that, if you can charge the Nerdies a high price and the Normies a low price, you can get the best of both worlds. High prices on some units, and high volume on others.

For this to work, though, a business needs to segment the market into Nerdies and Normies. If Professor Charles Xavier—the world’s most powerful telepath—ran a bar, he might be able to pull this off. You, a Nerdy whiskey connoisseur, saunter up to the bar. Professor X reads your mind and figures out that you are willing to pay $20.00 for a pour of Lagavulin. He offers to sell you a pour for $19. Your Normie friend can’t tell the difference between a Speyside scotch and an Islay scotch. (Is he really your friend?) Professor X reads his mind and charges him $10.00.1 Economists call this perfect price discrimination. Professor X knows exactly each customer’s willingness to pay.

Real world businesses don’t have Professor X’s amazing ability to read minds, so they have to use cruder methods to separate the Nerdies from the Normies. But while perfect price discrimination is fairly unrealistic (though universities get astonishingly close by charging the same tuition but offering different levels of financial aid), it highlights two important effects of price discrimination more generally:

- 1. With price discrimination, sellers get more of the gains from trade. The buyer of Lagavulin only gets $1 of consumer surplus, but Professor X gets $19—the price he paid for it.

- 2. Fewer consumers get priced out of the market. If Professor X had charged $12 for the scotch, your Normie friend would not have gotten any at all.

Focusing on the first condition, price discrimination strikes many first-time economics students as a bad thing. It’s another case of producers—especially Big Bad Corporations—extracting all the gains from economic cooperation for themselves. (This, of course, ignores the fact that consumers in one market are producers in another.) But taken together, the two conditions underwrite the greatest artistic achievement in mankind’s history: big budget comic book movies.

Fixed Costs and Price Discrimination

Tony wants to put on a puppet show. Putting on a puppet show involves fixed costs that only have to be paid once. To make the puppets, pay the writers, and create the sets costs Tony $8. Each performance adds $1 to his total cost. That includes wear and tear on the puppets and sets, contracting with a venue, and the (meager) opportunity cost of Tony’s time.

Tony has two potential consumers: Dan is Nerdy for puppet shows. He is willing to pay $8 to see one. Geoff is less enthusiastic. When it comes to puppets, he is a Normie who is only willing to pay $4.

What should Tony charge for a play? If Tony charges $4 per ticket, both Nerdy Dan and Normie Geoff are in. But he’ll only make $8, not enough to cover his fixed costs plus his cost per performance ($8 + $1 = $9). If he charges more than $4, Geoff isn’t interested. So the most he could make is $8 from Dan.

But what if Tony can price discriminate? If he can charge $7 to Dan and $3 to Geoff by offering two separate performances, he can make enough to cover his fixed costs and the cost per show. This is exactly how modern blockbusters work.

Separating the Nerdies from the Normies

The simplistic example of Tony’s puppet show illustrates exactly how big budget movies work. Blockbusters have a very high fixed cost. Large casts full of famous actors, expansive sets and props, and—in the past couple decades—armies of talented people and sophisticated machinery generating visual effects. But once the movie is made, the cost of an additional screening is much lower. To make back those fixed costs, movie studios need to separate the Nerdies from the Normies. How do they do this?

On opening weekend, Nerdies like me pay a premium price to watch the latest Marvel Studios production. In fact, my wife and I usually go twice: once on opening night, and again later in the weekend for brunch. This allows us to see the movie largely spoiler free and on the big screen. We usually buy whatever special pint glass the Alamo Drafthouse releases, with licensing fees going back to Disney.

These sorts of complementary goods also help separate the Nerdies from the Normies. The classic example is cheap printers with expensive ink refills, which allows heavy users to subsidize the printing of light users. For big blockbusters, this often takes the form of co-branded merchandise. Toys and apparel are the most conspicuous examples, but these days you can find nearly anything with a Marvel character slapped on it.

Over the coming weeks, slightly less Nerdy Nerdies catch the movie on T.A.C.O. (Tickets Are Cheaper On) Tuesday or a matinee showing. Matinee showings are price discrimination par excellance: those who can see a movie during the day have more flexible schedules and thus more substitutes for how to spend their time. Those who work regular hours are constrained to the evenings, so theaters discount daytime showings to fill as many seats as possible during the day. A few months later, second-run theaters (known as dollar theaters when I was growing up, but I bet that has changed) show the movie at an even lower price.

The whole process repeats itself with the home video release.2 First it comes out to buy. Nerdies like me have it preordered (usually in SteelBook form that costs $5 more). The sticker price is higher for a blu-ray than a theater ticket, but the price-per-viewing drops dramatically, especially for families with kids. After that, it becomes available rent on-demand. For $6 or so, the entire family can watch it once. Then it lands on an all-you-can-watch monthly streaming service, like Netflix or Disney+, or to a premium cable channel like HBO. Regular cable channels get to show it after that, and eventually it comes to free over-the-air network television.

At each step of the way, the movie becomes an attractive purchase to buyers that are progressively more Normie. Time serves as the instrument of market segmentation, allowing studios to charge a high price to the Nerdies and a low price to the Normies. These days, most tech-savvy consumers can wait until a movie hits streaming before watching it because most consumers are Normies about most movies. But thanks to the exuberance of Nerdies like me, for only pennies they get to see spectacularly crafted and very expensively produced movies.

The Streaming Gambit

That brings us back to Mulan. Will Disney’s plan succeed? It depends. Can studios, going straight to streaming, still sort out the Nerdies from the Normies? Will the Nerdies pony up an extra $30 to watch the movie now, while the Normies wait to have access as part of their normal $7 a month subscription? Dozens of factors are at play.

By going straight to online, studios give up a number of steps in market segmentation. They effectively collapse the opening weekend and digital purchase markets into one. A $30 price point will scare some Nerdies away, while appealing strongly to those with families. For a family of four, $7.50 per person—and popcorn purchased at the grocery store instead of at theater prices—will be a steal.

Some Nerdies are Nerdy about the cinema experience, others only about seeing the movie as soon as possible. Those attitudes have probably shifted as the quality of televisions and home theater setups has dramatically increased over the past two decades. Variety recently ran a survey that suggests most people would be willing to watch upcoming blockbusters at home, even if they might prefer the theater. Trolls: World Tour did remarkably well, making over $70 million off of content-starved, sheltered-at-home families. Disney needs more sales than that for Mulan to turn a profit. But the Mouse has one key advantage: it owns its own streaming service.

When a moviegoer buys a ticket, 60% of the ticket price typically ends up with the studio. This number varies from one country to another. The rest goes to the theater and any third-party ticket merchants, such as Fandango. By offering Mulan through Disney+, Disney gets to keep a much bigger percentage of the ticket sales.3 Mulan was projected to have an $85 million domestic opening. With over 60 million Disney+ subscribers, Disney needs less than 5% of its subscribers to buy Premier Access to match the return on that opening (since they keep a larger revenue share). That’s only opening weekend, and only domestic (the numbers are much more complicated for international because of the different share in ticket prices), but it shows that the gambit might well pay off.

Of course, price discrimination is far from the only economic concept at play in this move. Other factors include:

- • Opportunity cost: When it comes to blockbusters, one resource is fairly fixed: release dates. Blockbusters rarely go head to head, because they need the Nerdies to turn out in big numbers on opening weekend across as many screens as possible. If studios hold onto the big blockbusters they have made, they forego potential release dates for future blockbusters.

- • Economic profit: If opportunity costs are fully accounted for, the profit maximizing strategy is the same as the loss minimizing strategy. Instead of the dawn of a new business model, this may be a stopgap to stem the bleeding during the pandemic.

- • Complements: Disney probably has mountains of Black Widow merchandise sitting in warehouses. That merchandise will move a lot faster if the film comes to Premier Access rather than again delaying its theatrical release.

The real billion-dollar question may be piracy. When a movie releases first in a theater, the only pirated copies that are readily available are handheld camera recordings of the screen in a theater. The picture is bad. The sound is worse. And if someone in front of the camera gets up to use the restroom, home viewers get the real thrill of the theatrical experience. But once Mulan goes live on September 4—unless Disney has perfected a secret and miraculous encryption technology—there will be virtually perfect clones of the file that Disney is streaming to its customers available the same day.

Piracy is a real concern. But it is important to remember that the market for digital music and movies arose after widespread file sharing was already common. Digital media distribution has been so successful that some worry that the future of physical media is in jeopardy. Some consumers object to piracy on principle. Some simply value the convenience and safety of buying through official channels. And some are willing to pay to support content creators that they particularly like. If studios want to release blockbusters straight to streaming, they are probably banking on their Nerdy customers falling into that last group. But the fact remains that the higher the price, the more people will pirate a film. Is Mulan‘s $30 price point low enough to mitigate piracy and high enough to cover Disney’s fixed costs? We will see.

The Future of Movies

What happens after the pandemic has subsided? Will movie studios return to the older model, or will there be a new normal? One possibility is that COVID-19 has accelerated changes that were already on the way.

Over time, the window of time between the theatrical and the home release of films has shrunk. When I was growing up it would typically take about 6 months. Now 3 months is closer to the norm. How small might that window get? It might shrink to zero. A week before Mulan‘s scheduled release, Bill and Ted Face the Music will release simultaneously in theaters and on video on demand. While it does not have nearly the budget Mulan does, it is another experiment that studios will be eagerly watching.

Money has value over time. If studios can compress the time separating the Nerdies from the Normies—while still keeping them separate—they might be willing to take a small hit from piracy. While the standard window between theatrical and home releases may not shrink all the way to zero, it is highly likely that it will shrink more as studios such as Disney and Warner Brothers develop their own streaming services.

Theaters are the obvious losers from this trend. Variety‘s report suggests that many consumers still prefer to see blockbusters in a theater, but many consumers will choose to stream from their couch rather than going out. For someone like me, who wants to see a Marvel movie opening night but finds the behavior of other theater-goers generally obnoxious, the chance to stream at home from opening day would be a no-brainer. To get movie goers into the cinema, theater chains are going to have to offer service above and beyond the movie itself. I predict that, as these trends continue, the share of premium movie experiences as a percent of the total will increase. A higher share of screens will be IMAX or Dolbyvision and a higher share of theaters will offer table service, alcoholic beverages, and other amenities.

But a recent legal change might slow this move to streaming. In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled, on anti-trust grounds, that movie studios could not own theaters. That ruling was recently reversed.4 If studios can get a higher share of revenue from both streaming and from owning theaters, the calculus driving the Mulan decision might change. But ultimately, of course, this will depend on consumers: if other companies are offering straight-to-streaming blockbusters, studios might have no choice but to follow suit. Even the most powerful media companies have to mind the gap between the Nerdies and the Normies.

Footnotes

[1] Professor X’s ability to know you and your friend’s willingness to pay is not a sufficient condition for price discrimination. He also needs to make sure your friend doesn’t pay the lower price for two scotches and share one with you. This is sometimes called the no arbitrage conditions.

[2] A puzzle for my price-theory savvy friends. The digital release of modern blockbusters to own at home usually precedes the physical media release by one week. Why?

[3] The exact amount depends not only on payment processing charges, but also on whether Disney will allow purchase directly in-app. If that is the case, some app stores take a cut of the purchase.

[4] See “Studios Can Now Own Movie Theaters Following Judge’s Ruling,” by Jeff Sneider, Collider, Aug. 7, 2020, for more information.

*Adam Martin is Political Economy Research Fellow at the Free Market Institute and an assistant professor of agricultural and applied economics in the College of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources at Texas Tech University.