The Natural Law of Money

By William Brough

William Brough was born in 1826 in Kelso, Scotland. In his early childhood, the family moved first to Canada and then to Vermont. He began to study medicine but gave it up for business. He moved to New York in 1849 and then to Pennsylvania, where he was a pioneer in the development of the oil industry. He became the first president of the Oil Producer’s Association, and was involved in some important U.S.-Russian oil ventures. He retired in 1885, devoting his time to the study of social and economic subjects and to the writing of two books on money. A chaired professorship at Williams College is named in his honor.In

The Natural Law of Money, William Brough argues forcefully that privately-supplied money offers benefits not offered by government-supplied money.Brough’s analysis includes a discussion of Gresham’s Law. Gresham’s Law is commonly summarized by the catchy phrase “bad money drives out good.” It is just as commonly misunderstood. To understand Gresham’s Law, just remember this one simple requirement for it to hold: Fixed exchange rates.Historically, coins minted of valuable metals like gold or silver frequently became “bad” when they were clipped or shaved, making them weigh less. Coin-defacers could profit by shaving bits off of good coins and then reselling the metal clippings. Shop-owners, too busy to weigh coins for every transaction, were generally content to accept clipped coins at face value, so long as they could later spend those coins at that same face value. In daily transactions, the clipped coins were identical to the unclipped coins–they traded 1 : 1. Once this cycle got started for a currency, the bad coins quickly replaced the good ones, as coin-defacers snapped up and clipped any good coins in circulation. Thus, a gold coin stamped by the government with the value of one dollar might typically contain increasingly less than a dollar’s worth of gold over its lifetime. Eventually a critical point would occur, as the holders of bad coins became worried that other sellers would no longer accept their degraded coin at face value. Those left holding the bag stood to lose a great deal.In the modern world of fiat paper currency, the exact same effect occurs if a money’s quantity is relatively increased by its issuing Central Bank. Its value declines in principle, but it may temporarily be accepted at its stamped face value by those using it for daily transactions or to purchase other currencies, in the expectation that it will retain or return to that stamped value so it can be spent without loss. If the government further requires that the bad currency be exchangeable with another (good) currency at face value (i.e., at a fixed exchange rate), the bad currency will most certainly replace the good one in circulation. Why not accept a piece of paper worth less than a dollar if you can instantly buy with it another currency worth a full dollar? Why not keep any good pieces of paper under your mattress, and simply spend–recirculate–the bad ones? “Good” currencies are hoarded by the knowledgeable or used in illicit trade (because black market transactions typically involve large quantities of cash, which has to be accumulated and held by someone, risking an interim decline in confidence in its value), leaving the “bad” currencies in daily circulation.Gresham’s Law, so obvious and disturbingly critical to daily life that it was discussed in the streets for centuries, does not seem very relevant today. Why not? Gold coins of verified weight are good currency–why do they not drive paper monies out of existence? Because Gresham’s Law requires fixed exchange rates–exchange rates between the “bad” and “good” money that are fixed either by law, custom, or expectations. When coins are clipped but their stamped values trade 1 : 1 with unclipped coins–a fixed exchange rate–the bad coins soon drive out the good ones. When fiat money values are eroded by the increased supply of one relative to the other, but their relative legal values for transactions are mandated by government restrictions, the inflated currency drives out any available uninflated one. If gold or silver coins are required by law–fiat–to exchange with paper money at a fixed rate, and afterwards the quantity of paper money increases relative to that of the precious metal, the paper money will supplant the coin in daily transactions. Many other historical examples abound. The key factor in every case is fixed exchange rates between the bad and good currencies.But if the currencies’ values are instead determined by the market–that is, if they “float” relative to each other–then the clipped or overly-supplied money simply loses value (“depreciates”). Instead of the bad currency supplanting the good one, both currencies can exist side-by-side in circulation, trading at the market rate of exchange. The market participants have an incentive to keep tabs on the relative supplies or market exchange rates because no one wants to accept at face value money that will be worth much less when it comes time to spend it.Consequently, today, flexible exchange rates, supplied by nations implicitly competing in world money markets and simultaneously allowing their citizens access to those international money markets, enable people to substitute quickly their holdings of their domestic currencies for other currencies if they lose faith. The euro competes daily with the British pound, the U.S. dollar, and the currencies of Asia, Eastern Europe, and any other currency that gains a reputation for retaining its value–all of which helps keep values and monetary policies in line. Having suffered through enough fixed-exchange-rate tribulations and inflationary crises, many nations float their exchange rates and allow citizens to hold and use other currencies, at least to limited extents. Emigration allows further competition in money choices; and improved communication via computers allows instant access to information about international conditions affecting money supplies and demands. Thus, Gresham’s Law does not often rear its head in discussions. But Gresham’s Law still holds when rates of exchange are fixed; and it remains an Achilles’ Heel in discussions of returns to gold standards, unified currencies, or fixed (including managed) exchange rates. In money, as in all goods, market competition helps keep supply and demand in line.Does international competition in currencies effectively substitute for private competition? What conditions optimally determine the areas over which a single currency–the most extreme example of fixed exchange rates–can effectively operate? These questions excite international economists today.William Brough is one of only a few writers from the late 1800s who correctly explained Gresham’s Law, as well as many other matters concerning money supplies and these exciting matters of competitively supplied money. For more works on money supply from the late 1800s-early 1900s, see:Primary resources (historical order):

Bagehot, Walter,

Lombard Street (first published 1873)

Jevons, William Stanley,

Money and the Mechanism of Exchange (first published 1875). See, on Gresham’s Law,

Chapter 8, pars. 27-34.

Newcomb, Simon,

The ABC of Finance (first published 1877)

Laughlin, J. Laurence,

The History of Bimetallism in the United States (first published 1885). Empirical evidence on Gresham’s Law.

Brough, William,

The Natural Law of Money (first published 1896)

Fisher, Irving,

The Purchasing Power of Money (first published 1911). See, on Gresham’s Law,

Chapter 7.

Mises, Ludwig von,

The Theory of Money and Credit (first published 1912)

Cannan, Edwin,

“The Application of the Theoretical Apparatus of Supply and Demand to Units of Currency” (first published 1921)

Suggested Secondary Resources (alphabetical by author):

Mundell, Robert, Optimum currency areas. Online, see

International Economics, particularly Chapter 12,

A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas.

Timberlake, Richard H.,

“The Government’s License to Create Money” (

Cato Journal, The Cato Institute, Fall 1989). Online pdf file with helpful discussions of Brough, plus useful bibliography.

White, Lawrence H.,

“Competing Money Supplies,”The Concise Encyclopedia of Economics. Online at the Library of Economics and Liberty.

White, Lawrence H. and George Selgin,

“Why Private Banks and Not Central Banks Should Issue Currency, Especially in Less Developed Countries” Online at the Library of Economics and Liberty, April 19, 2000.

Lauren Landsburg

Editor, Library of Economics and Liberty

August, 2003Special thanks to George Selgin, Associate Professor of Economics at the Terry College of Business, University of Georgia, for biographical information on William Brough.

First Pub. Date

1896

Publisher

New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons

Pub. Date

1896

Copyright

The text of this edition is in the public domain.

CHAPTER V.

THE MONETARY SYSTEM OF CANADA AS CONTRASTED WITH THAT OF THE UNITED STATES.

CANADA to-day, with a gold basis of about thirteen million dollars, supplies all her monetary needs with great efficiency; she is not only able to supply all her own legitimate wants, but has for many years rendered substantial aid to our western people in the movement of crops in the autumn; this was notably the case in regard to the heavy crops of 1891.

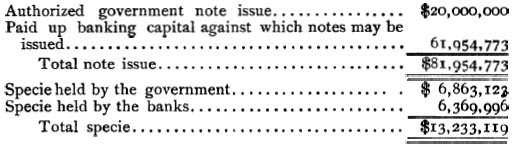

Canada’s total authorized banking capital is something over seventy-five million dollars, and the paidup capital a little less than sixty-two million dollars. The banks are permitted to issue notes equal to the amount of their unimpaired capital; the average circulation of bank-notes is about thirty-five million dollars, and the till-money is about fifteen million dollars, leaving twelve million dollars in reserve for extraordinary contingent demands. The demand

for money during the harvest months is increased about twenty-five per cent., and the large bank-note reserve enables the banks to meet this special call for money without adding a fraction to the rate of interest; for when these notes are not in service, they are lying in the vaults of the banks without cost to the banks or to their customers.

There is no bond security for the bills; the only security is a first lien on the assets of the bank and on the double liability of the stockholders, the total amount of which security averages four or five times the total possible circulation, and seven times the average circulation. There is, besides, a note-redemption fund, contributed by the banks and held by the government for the immediate redemption of the notes of insolvent banks. This fund amounts to five per cent. of the total sum of notes in circulation during the previous year, each bank being required to keep its proportion good. The holder of a failed-bank bill has, besides, the guaranty of every solvent bank for the payment of his bill; the result is that every Canadian has a sense of complete security in the money of the country.

There has been no bank failure in Canada during the term of the present or of the preceding Banking Act (which latter dates from 1880), in which the

assets of the insolvent bank were not sufficient to pay all the bill-holders. So far as can be ascertained, there has been no general suspension of specie payment in Canada within the past forty years; there was certainly no suspension there in 1857, when the banks of the United States suspended, nor has there been any since that time.

In submitting Canada’s monetary system to the test of fundamental principles, the only defects we find are those which arise from legislative interference: her government has reserved to itself the right to issue legal-tender paper-money; the limit of such issue, as at present fixed by statute, is twenty million dollars, and of this total about nineteen million dollars has been put out. The government has also established a number of post-office and other savings-banks, competing with the corporate banks for the deposits of the people, thus crowding up the rate of interest upon the whole Dominion. As might be expected there is a bond security to the government paper-money. Gold being the only standard of value in Canada, this paper-money has for its basis of redemption fifteen per cent. in that metal, and for security ten per cent. in Dominion bonds guaranteed by the British government, and seventy-five per cent. in Dominion bonds not so guaranteed. The

government retains to itself the issuance of all paper-money of a lower denomination than five dollars; it also requires each bank to carry forty per cent. of its reserves in Dominion notes; there are, however, no statutory restrictions on bank reserves, that matter being left very properly to the judgment of the banker. A reserve that is fixed by statute may operate as an embarrassment, but cannot as a security. Bank auditing, bank statements published monthly, a strict holding of the banks to their obligations under penalty of forfeiture of their charters, and, added to these, individual punishment for irregular or criminal banking, are the best securities the public can have, and these Canada has provided.

No better example can be found to illustrate the divergence in monetary ideas between the banker and the politician than is furnished by Canada. In all the essential characteristics of banking, the former is abreast with the intelligence of his time, while the latter still clings to the old notion that the State can arbitrarily enforce credit. By making the Dominion notes legal tender, and then compelling the banks to carry forty per cent. of their reserves in these notes, the Canadian government has needlessly burdened the banks, and in so doing has betrayed ignorance of monetary law. The same principles govern the relation between debtor and

creditor, whether a State or an individual is the debtor; these principles operate with equal force in either case, and cannot be set aside with impunity.

There is no such thing as compulsory credit; the whole banking system of Canada rests upon a foundation of confidence; hence when the government exacts from the banks an enforced credit of forty per cent. of their reserves, it weakens this foundation, and with it the whole fabric of credit of the Dominion. But as the banks are amply able to meet every legitimate demand upon them for coin, the enforcing enactment is practically inoperative so far as the people are concerned, since no judicious banker would force these notes upon a customer who needed coin; and it is to intelligent and upright banking that Canada owes her great advantage in the possession of an ample currency which is at once safe, stable, and elastic. The large measure of individuality and freedom conferred by the Banking Act of Canada has evidently been inspired by bankers, as the government’s own monetary methods, if carried to their logical conclusion, are calculated to undermine credit.

Canada’s monetary system is a complete refutation of the argument so persistently advanced among us that there is not enough gold in the world to supply the money needs. The per-capita statisticians would

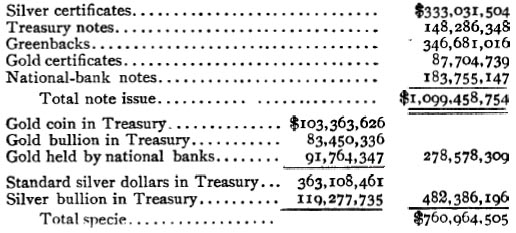

have us believe that we are helplessly dependent upon the volume of the precious metals for our medium of exchange, and yet here is a country that maintains a paper circulation of $16.40 per head on a metallic base of only $2.64 per head, without the least strain to her credit

*8; while our paper-money averages $16.40 per head with a metallic base of $11.36 per head, $7.20 of which is silver and $4.16 gold.

*9 In computing this ratio of $11.36 to $16.40,

silver is taken at its nominal value; but as the object is to show the very large proportion of metallic money used by us as contrasted with the proportion used by Canada, we must reduce our silver to its gold basis of sixty cents to the dollar, in order to make a uniform basis for comparison. Our ratio would then be $8.48 of metal to $16.40 of paper, as contrasted with the Canadian ratio of $2.64 of metal to $16.40 of paper. In computing the amount of metallic money in each country, only that is taken into the account which is held by the government and by the note-issuing banks of each country.

The fact that Canada’s medium of exchange is maintained at a proportionate cost of two-thirds less than ours costs us, is evidence in itself that her monetary system is in advance of ours; for, as has already been shown, the trend of improvement in money is now wholly towards the enlargement of credit and the relative lessening of the use of the precious metals. As the proportion of metallic money to credit-money is three times greater in the United States than it is in Canada, this difference against us, amounting to $378,673,350, may be regarded as just

so much productive capital abstracted from industry and converted into dead capital, for no one can doubt our ability to maintain as large a proportion of credit-money as Canada, if we will but adopt the proper legislative measures. The abstraction of this large sum from productive industry would be justified if it contributed to enhance the efficiency of our medium of exchange; as it does nothing of the kind, there is no way in which it can make the least return to the people from whom it is taken.

As all our paper-money is either government or national-bank money—and this latter is practically a government issue,—it does not come into commercial use until it is weighted with its nominal value in gold; whereas sixty-eight per cent. of the paper-money of Canada in commercial use represents credit. In so far as the business interests of our country are concerned, we have no credit-money, and the only possible advantage derivable from the use of paper-money is that it is more convenient than the metals. Whatever profit accrues from the issuance of paper-money, over and above the amount of metal held for its redemption, goes to the government, and operates as a direct tax upon the medium of exchange, and an indirect tax upon productive industry. As no bank in the United States has,

aside from its deposits, a dollar of paper-money which has not cost a dollar in gold or its equivalent, it cannot afford to keep such money idle; whereas, out of the total issue of eighty-two million dollars of paper-money in Canada, the banks hold about fifty-six million dollars, which represent credit, and which they can issue to their customers as required, or can carry in their vaults without cost to either bank or customer.

A comparison of the practical working of the two banking systems, as applied to agricultural industry, will illustrate more clearly the superiority of the Canadian system. Our western farmers and southern planters, as a rule, have not sufficient capital to carry on their work throughout an entire year without aid; they are consequently dependent for supplies between spring and autumn upon the local storekeeper and the local banker. Few of them indeed can get through the winter without using their credit; but when autumn comes and they have marketed their crops, there is an all-round settling of accounts. This necessarily calls for a much larger amount of money in the autumn than is required at any other time of year. As these conditions are fixed by the seasons, it becomes necessary that all business dependent upon or accessory to agriculture

shall be made adaptable to it. The country store-keeper, recognizing this fact, brings his business into conformity with it, and so does the local banker, as far as he can; but as he cannot exercise his functions with the same freedom as the store-keeper or the Canadian banker can, his ability to serve his customers is greatly curtailed. The Canadian banker makes his own paper-money, which, though in the form of bank-notes, because of their greater convenience, is nothing more than checks upon his own bank;

our local banker is compelled to get his money from the national government, and pay therefor its full denominational value in gold; and this is the case whether his bank is national or state.

The effect of this difference is that it costs the Canadian banker little or nothing to keep an ample supply of money on hand awaiting the contingent needs of his customers, while it costs our banker the full average rate of interest on the money so held; he is therefore obliged to keep his lendable money constantly employed in order to make it pay. Hence, when the demand for money is light at home, he sends his surplus to his corresponding bank say in Chicago or New York, where he is allowed interest upon it at a rate of a third to a half the average prevailing rate. Thus it is that the money of the in

terior drifts to the great commercial cities, where it can always find employment in speculative ventures, if not in legitimate commerce. A million bushels of wheat transferred speculatively ten times will lock up in margins as much money as the wheat is worth; and when these transactions are all liquidated, the result in wealth production to the nation at large is

nil.

But it is not necessary to own wheat in order to sell it speculatively; all that is needed is money. It would tax the ingenuity of man to make a money less fitted for industrial purposes and more easily drawn into these whirlpools of unwholesome speculation than our government money is. A money that has no local ties, no specific qualifications for definite work, but that is a “Jack of all trades,” will always elude supervision; and all paper-money, to be industrially productive, must have personal supervision. But as this implies an acquaintance with the workers and a knowledge of their work, the area of supervision is naturally circumscribed by individual limitations. While the bankers of the great cities where this money accumulates may, from their more commanding position, have a larger general knowledge of the monetary needs of the country than the interior banker can have, in the essential details of

lending money they are equally confined to their own field of supervision. What, for example, can a New York banker know of the qualities of the local commercial paper and collateral that is brought to him for re-discount by a Georgia banker? Practically nothing; he has to take the word of the Georgia banker, and however highly he may estimate that word, his mind is still impressed with the difference between a loan made at home upon his own judgment and knowledge, and one made at a distance upon the judgment of another; and this risk, whether real or imaginary, not only limits the disposition to lend, but raises the rate of interest charged.

The centralizing tendency of our money operates as another disadvantage to the rural banker by reducing his deposit account (a chief source of profit to the metropolitan banker), thus leaving the former mainly dependent for his profits upon the rate of interest charged. Hence we find that the Dakota farmer pays two to three per cent. per month for the money he borrows, while the Manitoba farmer pays three-quarters of one per cent. Notwithstanding the fact that our banks have relatively more capital than the Canadian banks have, they are not able to fully meet the legitimate demands made upon them. Dotted all over the West and the South are these in

dustrial banks at local centres, with veritable capital and under excellent management, which are yet unable to supply money that they would gladly lend if they could. Yet in the eastern States there is a prevalent belief that the call for more money which comes from the West and the South, comes only from those who have nothing to give in return for it; for it is said: “As money is always seeking a level, by flowing from points where it is in excess to points where it is in demand and can find safe employment at higher rates of interest, any one in good credit, or who has the proper security to offer, can always borrow what he needs.” Under a natural monetary system this would be so, but under our present artificial system it is not so. What better collateral security can there be than the products of the farm and of the plantation, and who more competent than the local banker to judge of the character of such security? Give him the same freedom as the local store-keeper, and he will serve his customers with the same thoroughness; it will not then be a question with the farmer as to how he shall get money to carry on his legitimate undertakings, but there will be a competition among bankers to serve him.

The situation in Canada to-day is that every legitimate demand for money is supplied. To be assured

of this fact it is not necessary for us to know the details of the actual transactions, for conclusive evidence is furnished in the published statements of the banks, which show that they have at all times a surplus of bank-notes in their vaults awaiting employment. While money is just as available at one point of the Dominion as at another, the rate of interest, although not the same at all points, is uniformly steady, and the difference in rate between one point and another is due to the difference in cost of conducting banking at different points. The merchants of Winnipeg borrow money at about the same rate of interest as is paid by the merchants and manufacturers of Montreal, the financial centre; and the farmers of the far West pay about the same rate that is paid by the farmers of Ontario. The importance of an ample supply of money and a stable rate of interest, in encouraging and aiding industrial productiveness, can hardly be over-estimated; for obviously no intelligent person will risk his credit and property in industrial operations that cannot possibly yield him any return within a year, unless he can know beforehand where he is to get his money and how much he is to pay for it.

But how can any one know anything about the future of

our money? It may have the intrinsic

value of gold to-day, and before the year expires be down to the price of silver; it may be abundant at six per cent. per annum when a business operation is undertaken, and be scarce at thirty-six per cent. before it is closed. These are the conditions that environ the workers, the wealth-producers of the United States, and they are the result of the government’s undertaking to be banker-in-chief for the nation. The demoralizing tendency of such conditions, which stimulate speculative ventures and discourage legitimate industry, needs not be pointed out. Nor need we be surprised that the farmers and planters are impressed with the belief that there is a moneyed conspiracy against them. In the interest of the whole country, is it not well that there should be a “greenback craze,” a “silver delusion,” and a continued agitation, until the most productive of all our industries is relieved from the incubus of a false monetary system, since these are the surest signs that there is an evil that needs correction?

If any more evidence is needed to prove the inability of our local banks to perform their proper functions, we have it in the fact that our western grain dealers are obliged to resort to Canadian banks for monetary aid. It is estimated that in the autumn of 1891 more than three million dollars were bor

rowed from these banks for use in Minnesota and Dakota alone. It may be said that the grain-dealers resort to the Canadian banks only because they can borrow at a lower rate of interest; but is not this of itself a full concession of our contention that our local banks are unable to perform their functions? It is solely because they are deprived of the right to issue their own notes on the security of the grain, as the Canadian banks do, that they are unable to compete with these banks. On what better security could paper-money be issued than on a bill of lading, or a warehouse receipt with accompanying insurance policy, which is the collateral given by the grain-dealer? The Canadian banks do not send gold into the United States to perform these services; they are able to come to our aid simply because their implement for effecting exchanges is of higher refinement than ours, and it is so by reason of its having less gold in its composition and more intelligence and integrity.

The idea which prevails among us that in some exceptional sense Canada is backed up by British capital, ignores the established principle that capital is not limited by nationality. The motives that move English capital are a sense of security and a higher rate of interest or of profit than

can be realized at home, and it will come to the United States on these terms just as readily as it will go to Canada. It was reported last July (1893) that Canadians “loaded with English capital” had appeared at Duluth as buyers of grain, when prices had broken in consequence of the hoarding of our currency. Now, we venture the assertion that if, as stated, Canadians went to Duluth to buy grain, they employed neither English capital nor English credit. A sight draft of the Bank of Montreal on its representative in New York for the purchase money would be a satisfactory form of payment to the seller of the grain; we may suppose the grain then shipped via the Lakes and St. Lawrence River to Liverpool, where it would be immediately convertible into English money; the bank meantime being in secure possession of the grain by bill of lading. But the bank could realize upon the grain before it arrived in Liverpool; it could authorize its agent in New York to draw a sixty-days’ bill of exchange on its agent in London, and this it could convert immediately into cash in New York, even in time to pay the draft from Duluth. It will be seen that the only capital that appears in this transaction is the grain itself, the credit of the Bank of Montreal being the medium of exchange.

The population of Canada is computed at five millions.

The amount of gold held by the national banks is from the report of the Comptroller of the Currency for the year ending October 31, 1893.

The population of the United States is estimated at sixty-seven millions.