Monopoly and Barriers to Entry: Old Wine in New Bottles

By Rosolino Candela

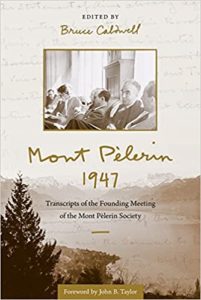

The year 2022 marks the 75th anniversary of the founding meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society organized by F. A. Hayek. What is particularly interesting is the fact that—as highlighted in the transcripts of that meeting recently published by Bruce Caldwell as Mont Pèlerin 1947 (2022)—the role of public policy in regulating market power and the necessity of laws enforcing competition remain a current academic debate.

The purpose of this essay is not to make any policy recommendations of my own, per se, in light of renewed calls for regulation against monopolies, particularly with respect to the rise of platform economies. Rather, it is to point out, as Mark Twain once put it, that “history never repeats itself, but it does often rhyme.” Therefore, my point is simply to render explicit some of the underlying assumptions upon which calls for anti-trust regulation are based. In doing so, I will highlight that—in the case for regulation of platform economies—this represents a new application of an old argument, one that had been discredited by economists working in the tradition of the Austrian school (Kirzner, 1979; Armentano, 1982), the Chicago school (Brozen, 1982), and the UCLA school of economics (Demsetz, 1973, 1982). This particular argument is the justification of regulation for the purpose of correcting a “market failure” associated with monopoly power based on economies of scale, which are regarded as a barrier to entry.

My argument can be distilled into three particular questions regarding the relationship between digital platforms and antitrust policy:

- (1) First, are markets “imperfect”?

- (2) Second, what is the relationship between entrepreneurship and barriers to entry associated with economies of scale?

- (3) Third, what role does limited liability play in reinforcing or eroding the conditions for corporate power, particular with respect to digital platforms?

I have argued elsewhere what it means for markets to be “imperfect,”1 but it is nevertheless relevant to highlight that the word “imperfect” is not only a by-product of our understanding of economic theory, but also has subtle yet important implications for public policy. Most economists would conclude—regardless of where they lie on the political spectrum—that because markets are “imperfect,” this means that they are flawed or suboptimal when compared to an “ideal market” of perfect competition in which no firm or group of firms can exercise monopoly power.

According to this narrative, government intervention is the deus ex machina that saves the market from its own “imperfections” through regulations that enforce “competition.” But rather than claim that a particular market is flawed, suboptimal, or non-ideal, another way to interpret the meaning of “imperfect” is as an act or process that is not thoroughly done, or incomplete. So, indeed, markets are imperfect, but precisely why they exist in the first place. They serve as a mechanism for error correction, learning, and entrepreneurial discovery.

None of this implies that markets operate outside of an institutional vacuum. Rather, it raises a particular conclusion with public policy implications. That is, if a market is imperfect due to monopoly power, representing a future profit opportunity for entrepreneurs to enter a particular market or industry, and if such an imperfection persists, then a barrier to entry must be stifling competitive entry.

One might argue therefore that monopoly power can persist due to barriers to entry not set up as a result of government privilege. This brings us to the second question: what is the relationship between entrepreneurship and barriers to entry associated with economies of scale? According to the argument first popularized by economist Joe Bain (1956, 1968) incumbent firms, by virtue of their ownership of capital, are able to enjoy a monopolistic or oligopolistic position—particularly if such a resource is prohibitively costly to purchase by many potential competitors. Capital requirements to realize economies of scale may serve as a barrier to entry, and therefore operate to confer imperfectly competitive market structures upon industries.

Thus, the most plausible argument in favor of regulation of digital platform economies is based on the notion of market imperfections due to barriers to entry associated with capital ownership and economies of scale, which in turn create the conditions for monopoly power. The role of digital platforms—such as Airbnb, Amazon, eBay, Google, and Facebook—is not to offer a specific product per se. Rather, such digital platforms serve to reduce transaction costs by acting as a connector between sellers that would otherwise compete separately with potential buyers (see Munger, 2018). Markets in which digital platforms have become important players are often characterized by a tendency towards concentration (Haucap and Heimeshoff, 2014). The implication here is that monopoly power is secured by the necessity for a firm to incur high fixed start-up costs in order to take advantage of the economies of scale due to the network effects provided by a platform.

While the argument that capital requirements constitute a barrier to entry is strengthened by the existence of scale economies, since these will increase the amount of capital needed to compete effectively, the argument does not depend on the superficial identification of large size with monopoly power. This is because entrepreneurial profits are not discovered by virtue of the fact that firm owners are owners of capital (Kirzner, 1979). Indeed, capital is required to later realize an entrepreneurial opportunity to enter a market, but the ownership of capital is a consequence of having first discovered that a profit opportunity exists, and therefore concentration of capital ownership does not necessarily constitute a barrier to entry that would cause monopoly profits. If this were the case, then every industry could realize higher profits simply by becoming more concentrated. Superior economic efficiency in pursuit of profitability tends to produce market concentration. Therefore, if concentration is a by-product of profitability—not necessarily its cause—due to the realization of efficiency gains, antitrust policy may have the counterproductive result of sacrificing the efficiency gains platform economies realize and raising prices for consumers (see Demsetz, 1973).

The conceptual distinction between entrepreneurship and capital ownership is particularly important, for it leads to the third question I raised: what role does limited liability play in reinforcing or eroding the conditions for corporate power, with particular respect to digital platforms? To address this question, let me begin by quoting economist Ronald Coase, who in his Nobel Prize address states that “a large part of what we think of as economic activity is designed to accomplish what high transaction costs would otherwise prevent or to reduce transaction costs so that individuals can freely negotiate and we can take advantage of that diffused knowledge of which Hayek has told us” (1992, p. 716).

According to the thesis first raised by Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means in their book, Private Property and the Modern Corporation (1932), since there is a separation of ownership among a diffuse group of shareholders—and since decisions are not made by such owners (i.e., shareholders) to whom profits accrue, but instead by a new class of corporate managers who control the firm—they find little personal incentive in providing corporate profits to shareholders. This separation of ownership and control in the corporate structure of firms creates the potential basis for corporations to exercise political power and influence (see Zingales, 2017).

However, the role of limited liability, which may be regarded as the source of corporate power, is also the very basis for its discipline and erosion. This is because “limited liability considerably reduces the cost of exchanging shares by making it unnecessary for a purchaser of shares to examine in great detail the liabilities of the corporation and the assets of other shareholders” (Demsetz, 1967, p. 369). Otherwise, “any extension of liability beyond the assets of the firm to the personal (extra-firm) assets of the shareholders must, in order to be enforceable, impair transferability of shares” (Woodward, 1985, p. 601). Although limited liability facilitates a distinction between ownership and control of the firm, this should not be regarded as a source of market power. Rather, limited liability becomes the source of market discipline of corporate management since it facilitates the ability of shareholders to buy and sell ownership shares on the stock market, deflecting corporate management from indulging preferences inconsistent with maximizing profit (see Demsetz, 1983).

In effect, limited liability allows potential entrepreneurs, who would otherwise be constrained if limited in their ownership of capital, to reduce the transaction costs of raising capital as a by-product of their entrepreneurial insight This allows markets to take advantage of the dispersed and tacit knowledge of potential competitors eroding the potential of corporate power. The point I am raising here is best stated by Israel Kirzner, who argued “where the corporate form of business organization permits a measure of independence and discretion to corporate managers, this is an ingenious, unplanned device that eases the access of entrepreneurial talent to sources of large-scale financing. Instead of the entrepreneur having to borrow capital—with all of the transaction costs we have seen this to involve—the corporate form of organization permits would-be entrepreneurs to hire themselves out to owners of capital as corporate executives. The capitalists retain formal ownership, permitting them, if they choose, to divest themselves easily of their shares in badly managed firms or, in the last resort, to oust incompetent management” (Kirzner, 1979, p. 104).

To conclude, I want to return to Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom, in which he refers to the law “as a kind of instrument of production” ([1944] 1994, p. 81). This is a particularly timely quote given the theme of the most recent meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society: Renewing the Infrastructure of Liberty. If the legal framework governing competition is analogous to a factor of production—such as land, labor, and capital—what we all wish to avoid is turning a legal of framework of rules (shared and enforced impartially across all competitors) into a framework of discretion for the sake of expediency to combat what appears to be a threat to open competition. If rules are abandoned for discretion, then the law will become a scarce factor of production—and like with any scarce resource, competition will result, only such competition will manifest itself in politics rather than markets in the form of rent-seeking and regulatory capture.

For more on these topics, see

Michael Munger on Antitrust. EconTalk.

Michael Munger on Antitrust. EconTalk.- “The Entrepreneurial Justice of the Market Process,” by Rosolino Candela. Library of Economics and Liberty, Jun 6, 2022.

- A Conversation with Ronald H. Coase. Intellectual Portrait Series, Liberty Fund Video.

Indeed, the surest way to secure a monopoly is the monopolization of a particular resource or factor of production, for such a barrier to entry can effectively preclude access into a market from new competitors. But such a condition can only be created if we open Pandora’s box by abandoning the framework of rules that constrain policymakers from exercising discretion. This will create the worst source of monopoly: control over legal discretion by firms through rent-seeking and regulatory capture. The implication here is that what entrepreneurs will identify as a profit opportunity will be contingent upon the relative returns to entrepreneurship, which are shaped by public policy. That is, public policy based on discretion will decrease the returns to productive entrepreneurship, which excludes potential competitors by learning to satisfy consumer preferences and increase the relative returns to unproductive entrepreneurship, which excludes potential competitors by learning to capture regulators.

References

Armentano, Dominick T. Antitrust and Monopoly: Anatomy of a Policy Failure. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1982.

Brozen, Yale. Concentration, Mergers and Public Policy. New York: Macmillan, 1982.

Bain, Joe S. Barriers to New Competition: Their Character and Consequences in Manufacturing Industries. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1956.

Bain, Joe S. Industrial Organization. New York: Wiley & Sons, 1968.

Berle, Adolf A., and Gardiner C. Means. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1932.

Caldwell, Bruce (ed.). Mont Pèlerin 1947. Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 2022.

Coase, R. H. “The Institutional Structure of Production.” The American Economic Review 82, no.4 (1992): 713–719.

Demsetz, Harold. “Toward a Theory of Property Rights.” The American Economic Review 57, no. 2 (1967): 347–359.

—— “Industry Structure, Market Rivalry, and Public Policy.” Journal of Law and Economics 16, no. 1 (1973): 1–9.

—— “Barriers to Entry.” The American Economic Review 72, no. 1 (1982): 47–57.

—— “The Structure of Ownership and the Theory of the Firm.” The Journal of Law & Economics 26, no. 2 (1983): 375–390.

Haucap, Justus, and Ulrich Heimeshoff. “Google, Facebook, Amazon, eBay: Is the Internet Driving Competition or Market Monopolization?” International Economics and Economic Policy 11 (2014): 49–61.

Hayek, F. A. The Road to Serfdom. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, [1944] 1994.

Kirzner, Israel M. Perception, Opportunity, and Profit: Studies in the Theory of Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1979.

Munger, Michael C. Tomorrow 3.0: Transaction Costs and the Sharing Economy. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Woodward, Susan E. “Limited Liability in the Theory of the Firm.” Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 141, no. 4 (1985): 601-611.

Zingales, Luigi. “Towards a Political Theory of the Firm.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 31, no. 3 (2017): 113-130.

Footnotes

[1] See “Are Markets Imperfect? Of Course, But That’s the Point! by Rosolino Candela. EconLog, May 18, 2020.

* This essay is based on remarks delivered on October 6, 2022 at the 75th Anniversary General Meeting of the Mont Pèlerin Society in Oslo, Norway (October 4–8, 2022). I am particularly grateful for comments and feedback offered by Peter Boettke, Don Boudreaux, Christopher Coyne, Larry White, and Amy Willis. Any remaining errors are entirely my own.

Rosolino Candela is a Senior Fellow in the F.A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, and Program Director of Academic and Student Programs at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.