What Arnold Schwarzenegger Can Teach You About the Economics of Property Rights

By Rosolino Candela

However, private property rights are not abstractions that are created independent of the particular circumstances of time and place. Rather, “when we recognize that transaction costs do exist,” according to Armen Alchian, “it seems clear that the partitioned rights will be reaggregated into more convenient clusters of rights” (1965, p. 820). As profound and important as these insights may be, they require frequent reiteration and illustrations to realize their importance, both in the classroom and for the general public. Yet, I would never have suspected that I could find such an interesting example to illustrate (1) how property rights tie consequences to one’s actions, (2) how property rights affect relative pricing, and (3) how transaction costs affect the allocation of property rights in pricing goods and services, from none other than Arnold Schwarzenegger.

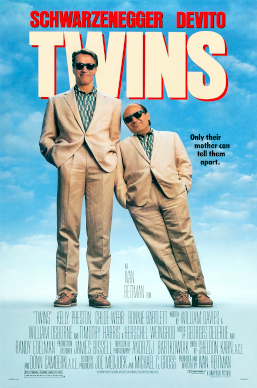

Among those of us who grew up watching Conan the Barbarian, The Terminator, Commando, Predator, True Lies, Eraser (the list can go on), Arnold Schwarzenegger is among the most iconic action stars of all time. However, one of my favorite Schwarzenegger films (co-starring Danny DeVito) is his 1988 blockbuster Twins. The relevance of that film for my point here comes not from the movie itself, but in an interview held by Graham Bensinger with Schwarzenegger,1 in which Schwarzenegger recounts the deals he had to make with the studio in order to be cast for the film.

The story of Schwarzenegger being cast for Twins, in so many ways, illustrates the three points I’ve outlined above. Although the director Ivan Reitman had wanted to work on a project with Schwarzenegger and to cast him in a comedy, the studio was highly reluctant to take the risk of Schwarzenegger starring in a comedy given his status as an action star. Stated in economic terms, over the course of the previous decade, Schwarzenegger had accumulated a valuable stock of asset-specific human capital as an action star, and the transaction costs of transferring such capital toward the production of another consumer service (in this case filming a comedy) seemed prohibitively high. In effect, there was a problem due to the high transaction costs of defining property rights between Schwarzenegger and the studio, specifically regarding the costs “of obtaining the information necessary to enter into and complete bargaining negotiations” (Kirzner, 1973, p. 227). Who would make the final choice about casting? Who would bear responsibility if the movie turned out to be a box-office bomb? Could Schwarzenegger reallocate his human capital as an actor toward producing a comedy? And, how would the contract be structured, between Schwarzenegger and the studio, to determine freedom of choice in casting, responsibility over the consequences of the film, and therefore residual payment for eventual profits or losses? Fundamentally, all of these questions illustrate that property rights pertain to defining a set of social relations, or defining rights over action (not defining rights over an object) regarding the expected ability to exercise choices over a good or service, including one’s own human or physical capital (see Furubotn and Pejovich 1972).

A clue to answer these questions can be found in Yoram Barzel’s Economic Analysis of Property Rights, in which he states the following: “The allocation of variability which maximizes the contractor’s wealth is the one wherein the ability of a contractor to affect the value of the mean outcome of the transaction is positively related to the share of variability he or she will assume” ([1989] 1997, p. 149).” Therefore, “if the party that will be more inclined to affect the outcome by varying the level of an attribute is put in control of that attribute, thereby becoming the residual claimant of its variability, losses will be minimized” ([1989] 1997, pp. 47-48). The unspecified “attribute” in this case that could vary the outcome of the film (in terms of its profitability), of which Schwarzenegger had particular knowledge (but the studio was unaware of) was his comedic ability. As he recounts in the interview, Schwarzenegger was so convinced of his comedic talent that he made an historic deal: he took no payment for his labor services as an actor in terms of a salary, thereby minimizing potential losses to the studio. Instead, he structured his contract with the studio in a manner that would assign him residual claimancy to any eventual profits. In effect, the uncertainty over the film’s success led Schwarzenegger to literally “take ownership of the situation” (to use an old phrase).

Ownership in this case was defined not by a right to an object, but in the appropriate sense in which property rights are understood, namely as a social relationship regarding who has the right to exercise choice and who bears the responsibility for such a choice. In effect, the presence of transaction costs, which could have otherwise prohibited a deal between Schwarzenegger and the movie studio, become an entrepreneurial profit opportunity that was monetized by Schwarzenegger by realizing an opportunity to restructure the allocation of property rights in a manner that was mutually beneficial not only between Schwarzenegger and the studio, but also director Ivan Reitman and co-star Danny DeVito.

More importantly, the lesson illustrated here has implications for understanding productive specialization under the division of labor. There is no inherently “exploitative” basis that predetermines the owner-laborer relationship, and therefore the structure of property rights. Rather, who is an “owner” and who is a “laborer” is a consequence of the manner in which property rights are structured. Rather than Schwarzenegger selling labor services to the studio, in which case the studio is the “owner” of the film, he instead became the “owner” by “selling” his property right to a salary from the studio for a share of potential profits (or potential losses) in the film. To be both free and responsible, therefore, requires knowledge that is context-specific to private property rights. In order to know whether an individual is responsible for an outcome (in this case attributing the success of Twins to Schwarzenegger), we must first know that he or she was free to exercise the choice that resulted in that outcome.

For more on these topics, see

- “Transaction Costs are the Costs of Engaging in Economic Calculation,” by Rosolino Candela. Library of Economics and Liberty, Jun. 3, 2020.

- Property Rights, by Armen Alchian. Concise Encyclopedia of Economics.

- “How Property Rights Solve Problems,” by David R. Henderson. Library of Economics and Liberty, Apr. 2, 2012.

Property rights are the institutional lynchpin in a free society that creates such context-specific knowledge, which is essential in order for individuals to learn and harness the potential of their creative powers through productive specialization under the division of labor. The point here is not that property rights were necessary for Schwarzenegger to be a comedic actor, but that property rights were necessary to learn if Schwarzenegger could become a successful comedic actor on the big screen. If he were not free to renegotiate property rights with the studio and put “skin in the game” in the manner he did, it would have been less likely (or perhaps taken longer) for both him and the movie industry to learn if he had what it takes. The realization of an extensive division of labor, one that facilitates wide-scale exchange, ultimately implies that individuals must also be free to divide and reshuffle property rights in a manner consistent with their particularized knowledge of time and place. Interestingly enough, that’s something that we can all learn from Arnold Schwarzenegger’s experience!

References

Alchian, Armen A. 1965. “Some Economics of Property Rights.” Il Politico 30 (4): 816-829.

Barzel, Yoram. ([1989] 1997). Economic Analysis of Property Rights, 2nd ed. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Furubotn, Eirik G., and Svetozar Pejovich. (1972). “Property rights and Economic Theory: A Survey of Recent Literature.” Journal of Economic Literature 10(4): 1137-1162.

Hayek, F.A. (1960). The Constitution of Liberty. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kirzner, Israel M. (1973). Competition and Entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Footnotes

[1] Bensinger, Graham. Interview with Arnold Schwarzenegger. YouTube (September 14, 2016).

* Rosolino Candela is a Senior Fellow in the F.A. Hayek Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, and Program Director of Academic and Student Programs at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University.