Orthodox Jewish Healthcare During the COVID-19 Pandemic

By Rachael Behr LaRose

It is important here to distinguish between economic and technical solutions in response to crises. Technical solutions often tend toward a single solution for all, but economic solutions often direct scarce resources to the pursuit of multiple and complementary rather than competing ends. Governmental recovery efforts tend to involve technical solutions or allocating a scarce means toward one centrally defined end. Community recovery efforts then produce economic solutions by valuing a spectrum of ends, including physical health, mental health, religious practices, and community, among others. This approach fosters a more comprehensive and adaptable recovery because it recognizes that people rationally value multiple and complementary ends more than the single end defined by authorities. For example, in response to a deadly and infectious virus, government efforts produce technical solutions that primarily address public health concerns through lockdowns and shutdowns to contain cases, hospitalizations and deaths. While potentially crucial for controlling the spread of diseases, these measures can overlook the broader array of community needs, and importantly, contain large tradeoffs (e.g., the toll lockdowns in 2020 had on mental health3, women exiting the labor force at higher rates4, high learning deficits among underprivileged children5, and many more). People rarely value one sole end, but instead seek to meet a variety of ends with scarce resources. It is likely incorrect to assume that pandemics are any different, even if the ends sought by communities may vary and change.

Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, it is unsurprising then that communities emerged as vital agents in disseminating accurate information and implementing localized responses, playing a crucial role in the recovery process. Co-production became particularly relevant during the pandemic as communities actively engaged in the production of essential healthcare services. Communities’ deep understanding of local contexts allowed for the development of context-specific measures, ensuring that recovery efforts were tailored to the unique challenges faced by each community.

For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Orthodox Jewish communities throughout the world provided a plethora of private health services, despite the stigma that Orthodox communities disregarded health concerns at this time.6 My coauthors and I researched Orthodox Jewish communities within the greater New York City area, investigating their endogenous responses to the pandemic. To do so, we designed a content-analysis of several large, New York City-based, Orthodox Jewish newspapers.7 My coauthors and I found that emergent narratives in Orthodox communities emphasized their care for health, building upon the literature of communities’ robust responses during crises. In particular, we found that rabbis and rabbinical councils provided private healthcare guidance; private, Jewish ambulances and medical response teams provided culturally and religiously sensitive healthcare; and, private, Jewish day schools provided ‘traditional’ public health services, like testing and tracing, while also prioritizing religious education.8

First, rabbis, rabbinical councils, and other Jewish advisory boards played a crucial role in providing health guidance during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City and surrounding areas by leveraging their trusted positions within the community to disseminate accurate information.9 Their influence extended beyond religious matters, fostering a sense of communal responsibility and adherence to health guidelines. Rabbis consistently conveyed a message which emphasized that, in adherence to elements of the Orthodox Jewish faith, one should prioritize health and the sanctity of life over religious practices, like in-person worship. This principle, known in the Jewish religion as pikuach nefesh, roughly translates to “saving a life”, and advocates that when in contention, preserving life must come before religious duties and observances. Many rabbis throughout the greater New York City area issued warnings to the community about distancing and masking, and many chose to close synagogues to in-person worship voluntarily. For instance, one Manhattan synagogue decided to close all services and classes, and the leading rabbi issued the following statement, justifying their closing by placing an emphasis on pikuach nefesh: “We strongly believe that safeguarding health is a Halakhic10 priority, one that requires us to act boldly to protect our community, our neighborhood, and beyond. We know that this requirement supersedes any requirement of congregational prayer.”11 One well-known rabbi in New York City wrote publicly, in the New York Jewish Week, that Torah readings and other Jewish thinkers like Maimonides show the Jewish people that “Halacha calls on us to be more careful with protecting our lives than with fulfilling ritual obligations.”12 Through my coauthors’ and my content analysis, we found several other instances in which rabbis directly refer to pikuach nefesh and the necessity to put the sanctity of life above religious obligations.

In addition to messages from individual rabbis, rabbinical councils often provided health guidance and chastised communities who did not adhere to guidelines through the pandemic, again largely basing their guidance on pikuach nefesh. Indeed, this was one of the more commonly cited reasons rabbinical boards put out for why they closed synagogues and encouraged at-home worship. For example, Rabbi Joseph Potasnik, President of the New York Board of Rabbis, stated that “Halachically… the preservation of life—maintaining health—is of paramount concern.”13 The New York Board of Rabbis, the Rabbinical Council of Bergen County, New Jersey, and the Long Island Board of Rabbis were just a few of the rabbinical boards issuing statements and advice through the pandemic; of course, nation-wide councils, like the Rabbinical Council of America, issued statements; so too did small, local councils across the country. These councils not only issued advice, but also chastised communities who did not place the sanctity of life above religious observance. For instance, the New York Board continued to issue guidance and criticism throughout the pandemic when Orthodox communities in Brooklyn broke crowd limits. In response to a Borough Park protest of COVID-19 public health restrictions in October 2020, the Board called the protests “shameful.”14

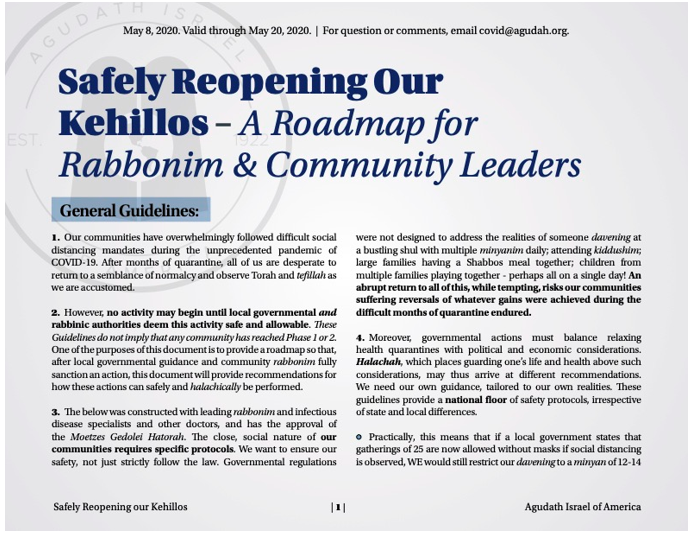

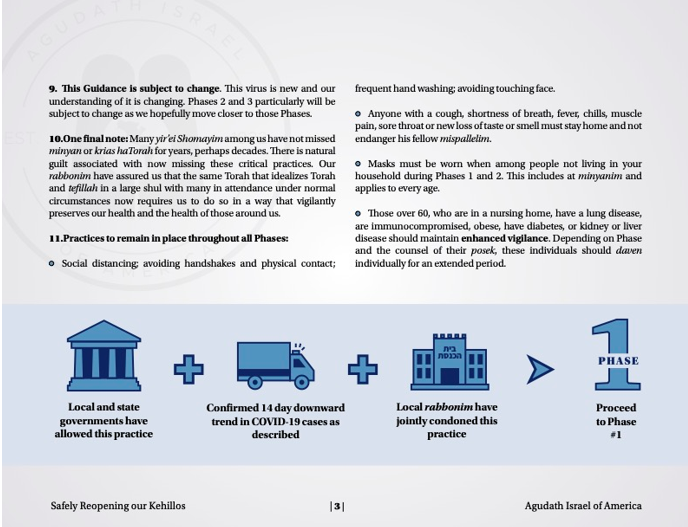

Last, these councils were also important in the re-opening process. Several large councils released their own guidelines for reopening synagogues and other areas related to worship, such as high-holiday worship and religious bathhouses called mikvahs. Importantly, each council tailored reopening guidelines to their communities’ needs. For instance, informed by a medical advisory panel and the guidance of Jewish religious-legal scholars (called Poskim), the Agudath Israel of America released an 11-point guide for gradually reopening synagogues (see Figure 2). Through our research, we found several other reopening guides that all mentioned the necessity for integrating local, on-the-ground knowledge into decisions around reopening.

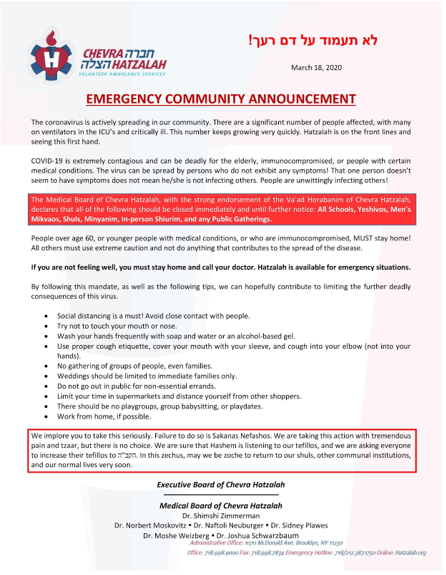

Another common theme from our content analysis were the services provided by Hatzalah. With origins in 1960s New York City, Hatzalah are community-based, volunteer, emergency medical organizations that provide ambulance and healthcare services that would become vital during COVID-19. Hatzalah provide swift and culturally sensitive responses in Orthodox Jewish communities, which during the pandemic, alleviated strain on the broader healthcare system. There are approximately nine Hatzalah chapters in New York, some of which have multiple divisions that serve numerous communities. For example, the Chevra Hatzalah chapter has fifteen branches throughout New York. A female counterpart to the Hatzalah in New York formed during the pandemic as well. After attempting to get approval from the state for years, the Ezras Nashim finally received approval to operate an ambulance during the pandemic. It is largely important for the same reasons the Hatzalah is important: certain groups prefer culturally sensitive medical care. In this case, many Orthodox women “might not wish to be treated by male staff for modesty reason.”15 These services were essential during the pandemic not simply because they provided culturally and religiously sensitive healthcare, but also because Orthodox communities, which already felt alienated and disliked during the pandemic, had access to healthcare providers they could trust.

In addition to providing ambulatory and healthcare services, Hatzalah also served as a general source of information and guidance for Orthodox communities. In August 2020, for example, amidst escalating outbreaks in Orthodox communities in New York City, local Hatzalah branches issued warnings about surging case rates and provided guidance to community members on appropriate courses of action. Figure 3 shows a common example of statements released by Hatzalah branches throughout the pandemic. What seems clear is that these services, existing in some places since 1965, are essential for public health provision, especially when healthcare must be provided with cultural and religious sensitivity. Throughout the pandemic, these bottom-up, organic, healthcare services were essential for Orthodox Jewish communities.

At the same time, Jewish schools also proved indispensable by implementing proactive measures such as testing and safety protocols, all while upholding the significance of Jewish faith and traditions within schools. This dual commitment to Jewish education and public health underscored the communities’ ability to pursue economic solutions rather than technical ones. Furthermore, it showcased the capacity of Jewish institutions to tackle pandemic-related challenges through bottom-up, community-based solutions rather than top-down, governmental measures.

While the Jewish community was criticized for being unwilling to shut down schools, a narrative that emerged from our analysis was that schools understood that to remain open, they must prioritize health. Orthodox Jewish schools implemented similar measures to other schools, such as keeping desks spaced apart, requiring masking, and adding plexiglass enclosures at tables. Moreover, some schools even provided and required COVID-19 rapid testing, despite pushback from parents who feared if too many students tested positively, the school would be forced to close. Like rabbis, rabbinical councils, and Hatzalah organizations, schools published guidance for parents on how to keep case rates down in order to keep schools open. Importantly, schools not only tried to limit the spread of COVID-19 within their premises, but also helped limit the spread throughout the larger community. For instance, some Orthodox schools urged caution amid the Jewish holidays: in a joint letter from Orthodox high schools across the United States, including several in New York City, administrators urged parents not to “schedule sleepovers” and to “[r]equire masks even for outdoor play dates. Remind children to keep their distance from one another. And forget about traveling during the upcoming Jewish holidays.” They continued, stating that their rationale was to ensure community safety and to keep schools open: “[W]e are writing this letter to communicate with you a number of important communal norms that must be adhered to in order to minimize the spread of COVID, thus preserving the health of our community and the viability of our schools.” In some cases, schools even asked children to quarantine if they knew that the family had attended large weddings.16

It should be noted that not all schools and school leaders complied when shut down by city or state mandates. During both the spring and fall of 2020, several predominantly Orthodox schools defied closure orders, resulting in tension between Orthodox communities and Mayor DeBlasio, as well as between Mayor DeBlasio and Governor Cuomo. This discord centered on differing perspectives regarding the strict enforcement of pandemic-related regulations.17

That said, it must be stressed that all the organizations that emerged in our content analysis (rabbis, rabbinical councils, Hatzalah, and Orthodox Jewish day schools) released guidance and health advice on how to keep communities safe. This advice was typically based on care for life (pikuach nefesh) and care for maintaining religious practices, such as continuing Jewish education. Importantly, these were the dominant themes that emerged from our content analysis of several large Orthodox newspapers. While we did find evidence of discord between Orthodox communities and government health authorities, the primary messaging from key leadership areas, including rabbis, rabbinical councils, Orthodox Jewish ambulatory and healthcare service organizations, and schools, all centered around ensuring the health and wellbeing of the community so that religious practices could continue. Leaders recognized that the Orthodox community would be unable to continue their religious practices as normal unless they provided for public health. Importantly, my coauthors and I found substantial evidence that emergent, community-driven public health institutions helped pursue local and public health goals.

For more on these topics, see

- “Public Health from the People,” by Byron Carson. Econlib, Feb. 5, 2024.

- A Guide for the Perplexed, by Moses Maimonides. Online Library of Liberty.

Emily Oster on the Pandemic. EconTalk.

Emily Oster on the Pandemic. EconTalk.

This discussion here has many important implications. First, Orthodox communities were singled out during the pandemic as caring little for public health and instead caring solely for religious observances. We find evidence that points to a different story: Orthodox community leaders stressed adhering to public health guidelines, and Orthodox private health services (like Hatzalah and schools) helped facilitate this, so that Orthodox communities could continue religious observances. Second, it is important to ask what ‘optimal public health policy’ truly is. Is it policy that follows what communities want and need, or is it policy that is dictated without regard for the multiple ends valued by the people it affects, and instead acts to solely meet one end? Future outbreaks may need to be informed by considerations of individual and community values and their resulting endogenous public health rules to avoid clashes between communities and public health authorities, and perhaps to provide more sustainable, effective recoveries.

Footnotes

[1] Elinor Ostrom, Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990).

[2] For a discussion of co-production during the pandemic, see Pedro Paniagua and Vishnu Rayamajhee, “A Polycentric Approach for Pandemic Governance: Nested Externalities and Co-production Challenges,” Journal of Institutional Economics 18, no. 4 (2022): 537-552.

[3] See, for instance, Vahia, Ipsit V., Dilip V. Jeste, and Charles F. Reynolds III. “Older Adults and the Mental Health Effects of COVID-19.” JAMA 324, no. 22 (2020): 2253-2254. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.21753. PMID: 33216114.

[4] Claudia Goldin, “Understanding the Economic Impact of COVID-19 on Women,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. w29974 (2022). She finds, in particular, that African American women excited the labor force at the highest rates, highlighting concerns of racial and gender disparity stemming from the pandemic and its related policies.

[5] See, for instance, B.A. Betthäuser, A.M. Bach-Mortensen, and P. Engzell. “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Evidence on Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Nature Human Behaviour 7 (2023): 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01506-4.

[6] New York City Mayor De Blasio, for instance, tweeted a message to the entire “Jewish community” that they needed to heed local rules, or they would be arrested. This led to large backlash from Jewish communities, since at this time, there was no data indicating that Jewish communities violated distancing and other local orders at higher rates than non-Jewish communities. See Matt Katz, “Jewish Americans Feel Scapegoated for the Coronavirus Spread,” NPR, May 13, 2020, https://www.npr.org/2020/05/13/854852779/jewish-americans-feel-scapegoated-for-the-coronavirus-spread.

[7] The content-analysis evidence discussed in this piece draws from my current research with Trey Carson, Tony Carilli, and Justin Isaacs, and is produced here with their permission. Running a content analysis involves systematically and objectively examining the characteristics and meanings of textual, visual, or audio content to identify patterns and themes. In our case, we examined prominent Orthodox Jewish newspapers, including the Jewish News Week, The Jewish Press, and Hamodia. Importantly, our research found further themes than what is discussed here, such as religious communities altering religious observances (like funerals) for these to be observed safely, but we only include three themes here for brevity.

[8] It should be noted that the Jewish community has traditions dating back thousands of years that emphasize health. See, for example, N.L. Muravsky, G.M. Betesh, and R.G. McCoy, “Religious Doctrine and Attitudes Toward Vaccination in Jewish Law,” Journal of Religion and Health 62, no. 1 (February 2023): 373-388 for a discussion on vaccinations and Jewish law.

[9] See Figure 1 for a typical example of statements from rabbinical councils during the pandemic.

[10] Halakhic refers to matters related to Halakha or Halacha, which is the collective body of Jewish religious law.

[11] Steve Lipman, “Chabad Rabbis Shut Down Brooklyn Synagogues,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, March 18, 2020. https://www.jta.org/2020/03/18/ny/chabad-rabbis-shut-down-brooklyn-synagogues

[12] Rabbi Noah Gradofsky, “To Protect Life During a Plague, Build Yourself a Fence,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, May 11, 2020, https://www.jta.org/2020/05/11/ny/to-protect-life-during-a-plague-build-yourself-a-fence.

[13] Stewart Ain, “Jewish Community Grinding to a Halt as Coronavirus Spreads,” NY Jewish Week, March 13, 2020, https://www.jta.org/2020/03/13/ny/jewish-community-grinding-to-a-halt-as-coronavirus-spreads, accessed October 11, 2023.

[14] David Israel, “NY Board of Rabbis: Violent Chasidic Protests ‘Shameful,'” The Jewish Press, 2020, https://www.jewishpress.com/news/us-news/ny/ny-board-of-rabbis-violent-chasidic-protests-shameful/2020/10/09/.

[15] Cnaan Liphshiz, “Brooklyn’s Orthodox Women’s EMT Service Gets Right to Operate an Ambulance After Years of Lobbying,” JTA, August 14, 2020, https://www.jta.org/quick-reads/brooklyns-orthodox-womens-emt-service-gets-right-to-operate-an-ambulance-after-years-of-lobbying.

[16] Quoted and drawn from articles by Shira Hanau, “Orthodox Day Schools Urge Covid Safety Ahead of High Holidays,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, September 17, 2020, https://www.jta.org/2020/09/17/ny/26-day-schools-urge-covid-safety-ahead-of-high-holidays, “‘This Is What We Expected’: Covid Closures and Quarantines Already Widespread at New York-Area Jewish Day Schools,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, September 15, 2020, https://www.jta.org/2020/09/14/health/this-is-what-we-expected-covid-closures-and-quarantines-already-widespread-at-new-york-area-jewish-day-schools, and “Messages in Jewish New York City School Parent Chats Advise against COVID Testing to Prevent Shutdowns,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, September 24, 2020, https://www.jta.org/2020/09/24/health/parents-at-jewish-schools-in-new-york-city-advised-not-to-test-for-covid-to-prevent-shutdowns.

[17] Shira Hanau, “In a Repeat of the Spring, Yeshivas in Brooklyn Are Operating despite School Closure Mandate,” Jewish Telegraphic Agency, October 15, 2020, https://www.jta.org/2020/10/15/united-states/in-a-repeat-of-the-spring-yeshivas-in-brooklyn-are-operating-despite-school-closure-mandate.

*Rachael Behr LaRose is Teaching Professor of Economics at Xavier University Department of Economics, Cincinnati, OH.

This article was edited by Features Editor Edward Lopez.