This fall, LIFE magazine has published a special issue commemorating the 50th anniversary of the movie M*A*S*H. Despite the hook, the issue focuses on the ensuing TV series, which ran from 1972 to 1983. Though the show has often been characterized as being politically left-wing, it actually is heavily classically liberal, celebrating the individual, civil liberties, and the market, and harshly criticizing anti-individualism, government compulsion, and government decision-making. In a series of essays, I examine the classical liberalism of M*A*S*H. This is Part 4. Part 1 is here. Part 2 is here. Part 3 is here.

When M*A*S*H debuted, the U.S. armed forces still used conscription to fill out its ranks. The peacetime draft began in 1948, following the expiration of World War II conscription, and included a special “doctor’s draft” for medical personnel. Selective service was vital to staffing up the U.S. military for both the Korean and Vietnam wars and was particularly despised by Vietnam protesters. Partway through M*A*S*H’s first season, the Pentagon announced that it would shift to an all-volunteer force, with the last inductions occurring before the TV season ended.

Among government institutions, conscription is one of the most disturbing. People of a particular demographic group — young men — are taken from their private lives and forced to work and live under strict government direction, at great risk to life and limb. The draft is regularly derided on M*A*S*H; as Hawkeye explains about his draft board in “Yankee Doodle Doctor” (s. 1), “When they came for me, I was hiding, trying to puncture my eardrum with an ice pick.”

No element of the show better represents opposition to the draft than the character Klinger. The show’s first seven seasons depict his many schemes to get discharged from the Army: trying to hang-glide out of Korea (“The Trial of Henry Blake,” s. 2), preparing to raft across the Pacific to California (“Dear Peggy,” s. 4), threatening to immolate himself (“The Most Unforgettable Characters,” s. 5), attempting to eat a jeep (“38 Across,” s. 5), pretending to believe he’s back home in Toledo (“The Young and the Restless,” s. 7). In “Mail Call” (s. 2), he claims his father is near death, hoping for a hardship discharge. Blake then flips through Klinger’s file:

BLAKE

Father dying last year.

Mother dying last year.

Mother and father dying.

Mother, father and older sister dying.

Mother dying and older sister pregnant.

Older sister dying and mother pregnant.

Younger sister pregnant and older sister dying.

Here’s an oldie but a goody: half of the family dying, other half pregnant.

Klinger, aren’t you ashamed of yourself?

KLINGER

Yes, sir. I don’t deserve to be in the Army.

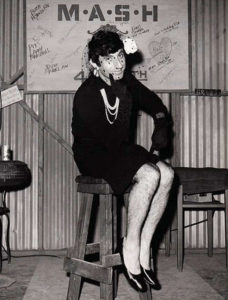

Klinger’s longest-running scheme is pretending to be a transvestite in the hope of earning a “Section 8” psychiatric discharge. Among the outfits from 20th Century Fox’s wardrobe shop that Farr wore (sometimes while puffing on a stogie) were Ginger Rogers’ Cleopatra costume (“April Fools,” s. 8) and a woolen coat of Betty Grable’s (“Major Ego,” s. 7), as well as reproductions of Dorothy’s pinafore dress from the Wizard of Oz and a Scarlett O’Hara gown from Gone With the Wind (“Major Ego,” s. 7), and a flare-torched Statue of Liberty get-up (“Big Mac,” s. 3).

Klinger usually provides comic relief, but in “War of Nerves” (s. 6) he delivers a serious condemnation of the draft. Confiding in Sidney, who previously knocked down several of Klinger’s Section 8 schemes, he says he really does fear he’s going crazy because of his attempts to get out of the Army. Sidney asks Klinger why he wants out:

KLINGER

Why? Well, there’s — there’s lots of reasons.

I guess death tops the list. I don’t want to die.

And I don’t want to look at other people while they do it.

And I don’t want to be told where to stand while it happens to me.

And I don’t want to be told how to do it to somebody else.

And I ain’t gonna. Period. That’s it. I’m gettin’ out.

SIDNEY

You don’t like death.

KLINGER

Overall, I’d rather lay in a hammock with a couple of girls than be dead — yes.

SIDNEY

Listen, Klinger. You’re not crazy.

KLINGER

I’m not? Really?

SIDNEY

You’re a tribute to man’s endurance. A monument to hope in size-12 pumps.

I hope you do get out someday. There would be a battalion of men in hoopskirts right behind you.

Comments are closed.