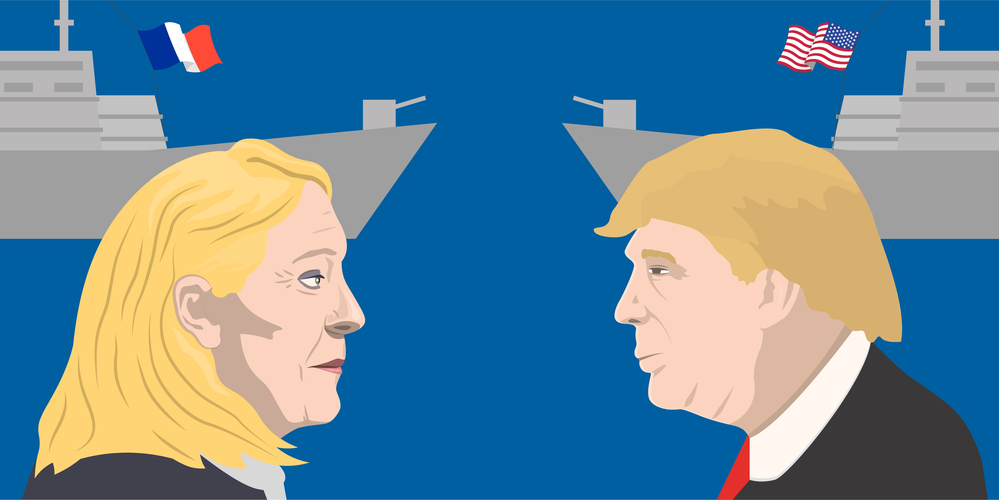

Marine Le Pen, the “far right” candidate who came close to Emmanuel Macron, the “centrist” one, in the first round of the French election said she wants to be “president of all the French.” In America, Biden similarly promised to be “president for all Americans,” but failed. Trump, more realistically (it did not happen often), promised to be the president of half the Americans. It is indeed impossible to be the president of all in America or France given what is now understood to be the job.

This can be seen with a simple model. Imagine a country where half the voters (plus or minus one) love wine and hate beer; and where the other half (plus or minus one) love beer and hate wine. Call that country “Syldavia” as in the adventures of Tintin (Hergé, Le sceptre d’Ottokar [Casterman, 1947], translated as King Ottokar’s Sceptre). We can also imagine that the voters in each group hide or supplement their tastes with strongly held values: the wine lovers strongly feel that wine production on family farms, being more labor intensive, creates more jobs; the beer lovers strongly favor the “good union jobs” in the beer industry.

Presidential candidate B (slogan: “Make Syldavian Beer Great!”) promises to ban wine and divert to beer all the resources currently devoted to wine production. At the opposite end of the political spectrum (who said voters had no choice?), candidate W (slogan: “Make Syldavian Wine Greater Still!”) promises to ban beer and divert to wine production all resources used in beer. As we say in French, “to govern is to choose” (gouverner, c’est choisir). Clearly, however, neither B nor W will be the “president of all Syldavians.”

Compromises can be imagined, including replacing beer and wine production by a single mixture made of X% wine and [100-X]% beer. But all voters would probably hate it and the compromise would make each of the candidates the president of zero Syldavian.

Assuming no “externality”—that is, no Syldavian is made miserable by the mere thought of somebody else drinking beer or wine—there is only one way for a candidate to be “the president of all Syldavians”: it is to let each and every Syldavian produce and drink whatever he wants; it is for the government to discriminate against no one. The model neglects a few other complications, but the general result seems unimpeachable.

The reader interested in more weighty complications should consider James Buchanan’s theories. My review articles at Econlib, “The State is Us (Perhaps), But Beware of It!” and “Lessons and Challenges in The Limits of Liberty,” may be helpful introductions.

READER COMMENTS

AMW

Apr 11 2022 at 5:23pm

Nice timing on your article: I just began reading “King Ottokar’s Sceptre” to my six-year old last week.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 11 2022 at 6:26pm

AMW: Great idea! He will love it.

Roger McKinney

Apr 12 2022 at 9:47am

Great points! Also, it was nice to remember Tintin. My kids loved him.

BS

Apr 12 2022 at 2:11pm

Kids, heck. I have the Tintin books and the Asterix books, and every couple of years read them through.

“There are no guilty pleasures; there are only pleasures.”

Sangam Rai

Apr 12 2022 at 9:51am

Simple but outstanding.

Jose Pablo

Apr 12 2022 at 1:00pm

One complication of your model is that neither candidate B nor candidate W truly believe in implementing the policies they themselves advocated during the campaing. After all, not even Trump built the wall or “reduced” taxes (increasing the deficit is not a way of reducing taxes, just of kicking them down the road, a very different kind of policy).

The Economist has a very interesting article on the “lies and fears”-based “modern democracy” and the increase of its prevalence:

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2022/04/09/fearmongering-works-fans-of-the-truth-should-fear-it

Apart from being “free to choose” the amount of wine or beer they want to consume, individuals should be “free to totally ignore” this bunch of disgraceful, unreliable, egocentric, self-serving people we use to call “politicians”.

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 13 2022 at 6:32pm

Jose: You may be right in your last paragraph, although replacing “totally” by “partially” might be prudent. The danger is that, otherwise, our current lying politicians will be replace by the Putin or Orban type. We know that they exist. (Thanks for the linked article, which I had missed.)

Weir

Apr 12 2022 at 6:26pm

Just want to point out that the president who said “we’re gonna punish our enemies and we’re gonna reward our friends” was Barack Obama. And the next guy said this instead: “It’s time to remember that old wisdom our soldiers will never forget: that whether we are black or brown or white, we all bleed the same red blood of patriots, we all enjoy the same glorious freedoms, and we all salute the same great American flag. And whether a child is born in the urban sprawl of Detroit or the windswept plains of Nebraska, they look up at the same night sky, they fill their heart with the same dreams, and they are infused with the breath of life by the same almighty Creator. So to all Americans, in every city near and far, small and large, from mountain to mountain, and from ocean to ocean, hear these words: You will never be ignored again.”

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 13 2022 at 6:19pm

Weir: I would argue that both statements are collectivist. Obama could avoid this criticism (if he wanted to) by replying that “our enemies” are thugs who want to abolish our common liberty. I don’t know how Trump’s logorrhea could avoid my criticism. It is not true that “we all bleed the same red blood of patriots.” Some Americans are not patriots in Trump’s sense. Most don’t bleed the same blood if only because they have different blood types. At worst, his cheap, cheesy, poetry-fake discourse reflects primitive social organicism. Each individual bleeds his own blood. Not all Americans “salute the same great American flag”: some burn it–even if Trump, in his 2016 campaign, suggested that they should lose American citizenship, despite the Supreme Court having ruled that flab-burning is protected by the Second Amendment. And he should have known that it is still very much a work in progress that all Americans may “enjoy the same glorious freedoms.” (By the way, you have a link to this interesting words from Trump?)

Weir

Apr 14 2022 at 9:00am

It was from Trump’s inauguration speech, when Hillary supporters with crowbars and hammers were smashing windows one mile away from the National Mall.

So at the very moment when Trump was saying “we must speak our minds openly, debate our disagreements honestly, but always pursue solidarity” you had the Hillary supporters proving your point with arson and rioting.

The Associated Press reports that they “smashed the windows of downtown businesses including a Starbucks, a Bank of America and a McDonald’s as they denounced capitalism and Trump.” They set fire to someone’s limousine.

The Associated Press: “Some protesters picked up bricks and concrete from the sidewalk and hurled them at police lines. Some rolled large, metal trash cans at police.”

I notice Hillary’s claim that foreigners and traitors had conspired together to steal the election from her was, of course, a prominent theme: “Outside the International Spy Museum, protesters in Russian hats ridiculed Trump’s praise of President Vladimir Putin, marching with signs calling Trump ‘Putin’s Puppet’ and ‘Kremlin employee of the month.'” And sadly it remains the case that Hillary is still insisting, even now, that the man in the Kremlin “pulls his strings” and that Trump is “beholden” to him.

Thomas Lee Hutcheson

Apr 13 2022 at 7:32am

“President of all ….” presumably just means that the politician is claiming to think that (almost) all citizens have common interests in a relevant range of policies. I think that is in fact the case. Freer trade, higher immigration of high-skilled people, lower deficits, cost effective reductions in net CO2 and methane emissions, maintaining democratic governance have very widely dispersed benefits and costs are potentially compensable. The problem arises when the politician in question has an incorrect model of which polices DO have widespread benefits (or is just lying and fully intend to govern in the interests of a certain subset of citizens’ status or income relative to others).

Pierre Lemieux

Apr 13 2022 at 4:45pm

Thomas: Two points: (1) “Common interests in a relevant range of policies” are less common as the “relevant range of policies” increases. (2) As Buchanan and Hayek have emphasized, common interests in rules are much easier to find than common interests in policies. In Syldavia, it would be conceivable to find a common interest in a rule saying that “Any Syldavian has the right to drink what he wants”; it would be impossible to find a common interest in candidate B’s or candidate W’s policy.

Comments are closed.