In my previous post, I described the effects of the oil reseller boom to explain why U.S. consumers paid record-high prices—even approximating the price of world oil—despite maximum price regulations at every transaction point to ensure the opposite result during the oil shortages of the 1970s.

Despite years of regulatory tailoring and thousands of committed administrators (consolidated in the U.S. Department of Energy in 1977), the gasoline lines reappeared in 1979 with oil cutoffs from the Iranian Revolution. Enough was enough even for President Carter, whose National Energy Plan of two years earlier was in shambles. With support from Democrats, a phased decontrol bill was enacted with a windfall profit tax that was accelerated into full decontrol by President Reagan upon taking office in early 1981.

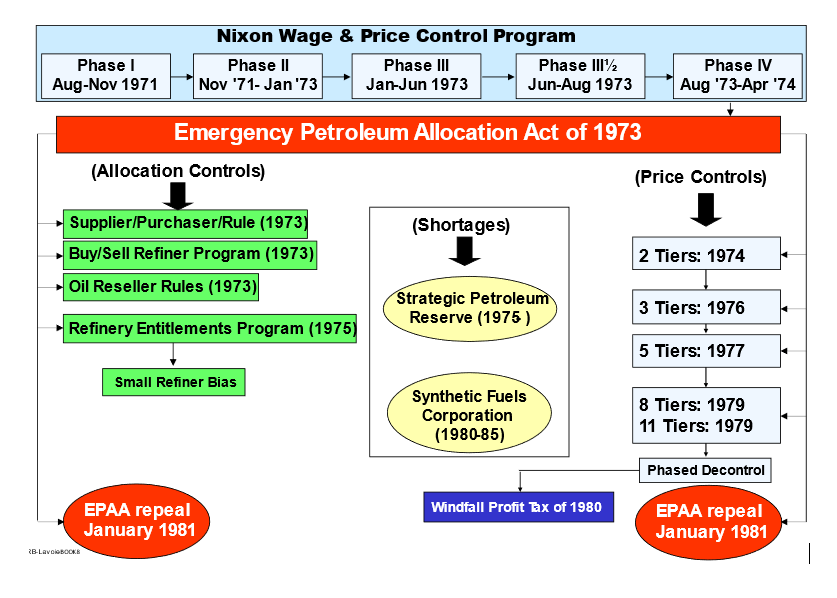

It had been planned chaos, to use a term of Ludwig von Mises. The initial EPAA regulations covering 27 pages in the Federal Register would be supplemented by more than 5,000 pages of amendments in its first two years. Under this law, there would be “no fewer than six different regulatory agencies and seven distinct price control regimes, each successively more complicated and pervasive.”[1]

The unprecedented peacetime exercise in cumulative intervention went far beyond the EPAA. Between 1977 and 1980, more than three hundred energy bills were considered in Congress. State legislatures considered many more. Before it was over, even the most anti-oil politicians had regrets. Senator Edward Kennedy (D-MA) complained about the “outrageous weed garden of regulation.”[2] James Schlesinger, the first head of the U.S. Department of Energy (created in 1977), called the experience “the political equivalent of Chinese water torture.”[3]

The regulatory tsunami included dozens of state and federal mandates for energy conservation. In the name of energy security, the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (1975) and the Synthetic Fuels Corporation (1980) were born, each introducing their own issues and challenges. “Gapism”—regulation, taxation, and subsidization intended to either increase supply or decrease demand—threw good money after bad in the price controls-shortage program.[4]

Conclusion

In reference to the 1970s oil crisis, Milton and Rose Friedman wrote,

The peacetime experience of oil shortages is a case study of public policy gone wrong, and predictably so. The good news is that maximum price controls as an energy policy was driven from the debate and is a political nonstarter today. The bad news is that so much damage was done in a futile quest to plan petroleum from the center. Additionally, a policy of “energy security” (in wait for a third oil shock, the gasoline lines of which would not come without price controls) created new bureaucracies and new programs that remain to this day.

History matters, and regulatory history informs public policy toward business. Never again.

Robert L. Bradley is the founder and CEO of the Institute for Energy Research.

[1] Joseph P. Kalt, “The Creation, Growth, and Entrenchment of Special Interests in Oil Price Policy,” in The Political Economy of Deregulation: Interest Groups in the Regulatory Process, ed. Roger G. Noll and Bruce Owen (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1983), p. 98.

[2] 124 Cong. Rec. S17071 (daily ed. June 9, 1978) (statement of Sen. Kennedy).

[3] Quoted in Daniel Yergin, The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991), p. 659.

[4] Edward Mitchell. U.S. Energy Policy: A Primer (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1974), pp. 17–26.

[5] Milton and Rose Friedman, Free to Choose (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1979), p. 219.

Comments are closed.