Back in the fifties, kids didn’t even have seatbelts. My dad tells me that in 1971 I came home from the hospital the old-fashioned way: In my mother’s arms. Nowadays, in contrast, we transport our babies using special infant carriers – and face a lot of propaganda about the right way to use them. (Consumer Reports claims that 4 out of 5 seats are installed incorrectly; Wikipedia cites a piece asserting that “In 1997, six out of ten children who were killed in vehicle crashes were not correctly restrained.” Hmm.)

Since I’m collecting the basic facts on child safety, I decided to take a quick look into this. The results:

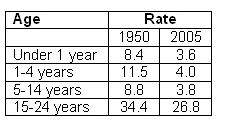

Youth Mortality from Motor Vehicle Accidents per 100,000

1. Motor vehicle safety has improved a lot less than you (or at least I) would have expected. In fact, it improved quite a bit less than average. The overall fatal accident rate for kids today is about a quarter of what it was in 1950. The motor vehicle rate is about 40% of its 1950 level.

2. Contrary to what you’d expect, infant car safety has not improved a lot more than the safety of older children. Dubner and Levitt sharply distinguish infant seats – which they consider a big improvement over “riding shotgun on mom’s lap” – from child seats – which they argue are no better than seatbelts. Looking at the raw facts makes me wonder.

3. Safety improved about as much for older kids (who usually just use seat belts) as it did for younger kids. So there must be many reasons why car travel is safer than it used to be; car seats can’t be more than one piece of the puzzle.

Suppose that 25% of the improvement in infant safety came from child seats. That’s 1.2 fatalities per 100,000. If you plug in a conventional $7M “value of life,” that comes out to $84 of value for your baby’s first year. Legality aside, it’s still probably worth installing a cheap child seat. But it’s probably not worth spending hours doing what I did six years ago: perfecting your installation technique. (Now, of course, that’s a sunk cost!) And if your cousin offers to take your kid to a movie, it’s almost definitely a mistake to refuse out of fear that you won’t transfer the seat correctly.

If the average American read this, I suspect that he’d consider me a bad parent just for thinking such thoughts. My response: A good parent is prudent, not paranoid. While you should put a high value on your child’s safety, it’s OK to find facts and weigh trade-offs. Would you be willing to drive an extra five miles with your child every week to save a little money at Walmart? If so, you probably shouldn’t be ashamed to learn that your seat installation technique is only average.

READER COMMENTS

David

Aug 22 2009 at 12:36pm

I think Dubner & Levitt concluded that most of the effect was due to getting kids in the back seat, car seat or not.

My impression from the data is that 15-24 is a bad age grouping. Persons age 15-24 being driven around by experienced drivers probably have a mortality rate around 4, or maybe closer to 8 for front seat. But 15-24 includes inexperienced drivers and the circumstances behind a lot of those crashes includes very high speeds, etc. I’d be interested to see the stats for say, age 35-44 and how that mortality rate improvement compares to 15-24.

John Thacker

Aug 22 2009 at 1:06pm

It’s possible that child seats and infant seats have improved the safety of children and infants, while at the same time wider use of shoulder belts and air bags that aren’t appropriate for children have improved the safety of older people.

David N. Welton

Aug 22 2009 at 1:35pm

> Motor vehicle safety has improved a lot less than you (or at least I) would have expected.

That number coming down by half probably doesn’t look so bad once you start considering the increased number of vehicles on the road, the average distance traveled, and the average speed. That’s my guess at least, I don’t have time to go look those things up, but the first one at least has to have increased a great deal, and I can’t believe the last one has decreased in all but the most congested areas.

Walt French

Aug 22 2009 at 2:08pm

Of course, these stats don’t tell us anything about non-fatal accidents, and the extent of injuries.

Restraints aren’t terribly significant in 65 mph head-ons. They can reduce death to survivable injury at 30 mph (roughly, the stats shown); and they can mean injury versus none for the 15 mph fender-benders. Those are the most likely scenario for a parent slamming on the brakes a bit late while shuttling kids to pre-school, friends, etc.

Meanwhile, you have a contract with your society, perhaps also with your God, to exercise prudent care with the little life entrusted to you. The $7mm figure notwithstanding, skipping obvious precautions as cost-inefficient is itself cost-ineffective in preserving your place in society. Save your breath for something more valuable.

RL

Aug 22 2009 at 2:14pm

Clearly some people think we should lock up our parents and grandparents en masse for reckless endangerment…

Mark Denovich

Aug 22 2009 at 2:31pm

Average vehicle miles per captia 1950: 3017

Average vehicle miles per captia 2005: 10,103

From: http://www-cta.ornl.gov/data/chapter8.shtml

Brandon Berg

Aug 22 2009 at 2:41pm

The meaningful statistic is deaths per million (or whatever) passenger miles. The lackluster decline in the 15-24 age group is almost certainly due to a dramatic increase in this group’s access to cars.

Nathan

Aug 22 2009 at 3:30pm

Walt–could you please explain what you mean by your comment that skipping cost-inefficient precautions is itself inefficient? Life is full of trade-offs. Even the most prudent parent can’t do everything to protect the life of his/her child. As Brian alluded to, driving is dangerous in itself. If you really wanted to take every precaution, you’d hire a baby sitter every time you went to the grocery store rather than take your kid with you. (Or hire a personal shopper, so you can stay safe at home too.)

The fact that Brian is willing to look logically and mathematically at the trade-offs he’s willing to make rather than just trying to eyeball it, as most people do, is praiseworthy.

TomB

Aug 22 2009 at 3:48pm

I would be interested in seeing how the average speed limit has changed. I was told by a trauma physician that when your speed reaches 70 miles per hour, the death rate from accidents spikes up dramatically. The reason is that the force of the sudden deceleration rips the aorta right off of your heart. No safety equipment can really stop it. Kind of gruesome. I am not a doctor, but I would imagine that for children the speed at which this is possible is much lower.

eccdogg

Aug 22 2009 at 3:58pm

The correct stat to measure the effectiveness of child seats has to be per vehicle mile traveled not per capita.

In the 50’s many women did not drive at all and many families had only one car (that dad took to work) plus cities were less dispersed. I am guessing that children particularly infants were in cars much less than they are today.

I know this would have been the case for both of my parents (who were children in the 50’s) families. Neither of their mothers drove until my parents were in highschool.

Milton Recht

Aug 22 2009 at 4:32pm

Motor vehicle accidents and fatalities are directly related to miles driven. For example, teenage girls have the same accident rate per mile driven as teenage boys but teenage boys drive more miles than girls drive and have more accidents and higher insurance rates.

In 1950, the vehicle miles per capita was 3029. In 2005, it was 10,087. See: http://www1.eere.energy.gov/vehiclesandfuels/facts/2007_fcvt_fotw469.html

All other things being equal, we would expect the fatality rate for infants and the other categories to be 3.3 times higher in 2005 than in 1950 (10087/3029). If one adjust the 2005 expected fatality number by the 3.3 factor, the improvement in fatalities is tremendous for infants and young children. Fatalities are one eight to one tenth of expectations.

I would even venture a guess that young children are driven in cars more today than in 1950. More live in the suburbs and more are driven to play dates, nursery schools, daycare and enrichment activities than ever. The improvement in fatalities rates for infants and young children is most likely even better than the one eight to one tenth rate.

Wilmot

Aug 22 2009 at 5:09pm

Walt thinks I have a contract with society to keep kids safe.

Why? Presumably because he, like most people, thinks children are important beyond anything else.

The problem I have with that is simply due to the fact that I don’t believe this. I hate the little buggers, actually.

Brandon Berg

Aug 22 2009 at 6:36pm

The reason is that the force of the sudden deceleration rips the aorta right off of your heart. No safety equipment can really stop it. Kind of gruesome. I am not a doctor, but I would imagine that for children the speed at which this is possible is much lower.

Neither am I, but I’m skeptical. Granted, it’s reasonable to assume that a child’s heart, being smaller than an adult’s, will not be able to absorb the same amount of force without fatal damage. But a child’s heart is lighter than an adult’s, so it will be subjected to proportionately weaker decelerating forces.

All else being equal, a small person should be able to withstand at least as much deceleration as a large person, if not more (because of the square-cube law. But a child isn’t just a small adult, so maybe not.

Brandon Berg

Aug 22 2009 at 6:38pm

Mark:

Vehicle miles per capita is helpful, but it doesn’t tell us exactly what we want to know, which is passenger miles per capita. Vehicle miles is a reliable proxy for the latter only insofar as the average number of occupants per vehicle has remained stable, which I doubt.

Dr. T

Aug 22 2009 at 8:12pm

Reasons why safety gains for kids in cars were not as great as suspected:

1. Wrong metric. As others above commented, we need to know deaths and accidents per mile travelled, not per 100,000 kids.

2. Average speeds are higher now than in 1950. Impact force goes up with the square of the speed.

3. Failure to use the safety devices. I have seen many unbuckled child passengers, some of whom roamed freely throughout the car. Presence of safety devices doesn’t equate to use.

4. Vehicle mix differed during the time period, with heavier cars the norm until the mid-seventies when more light cars were on the road. Heavier cars were the trend in the 1990s, and now the mix favors heavy cars. The worse mix is 50% light and 50% heavy because half the collisions will be light-heavy.

I did part of my pathology training in a medical examiner’s office. All the vehicular fatalities I saw were people who were not wearing their lap belts and shoulder harnesses. Child seats and lap belts + shoulder harnesses are remarkably effective in most crashes.

Dr. T

Aug 22 2009 at 8:35pm

“The reason is that the force of the sudden deceleration rips the aorta right off of your heart. No safety equipment can really stop it. Kind of gruesome. I am not a doctor, but I would imagine that for children the speed at which this is possible is much lower.”

I’m a pathologist, so I’m qualified to answer. The deceleration force required to tear the aorta is large. I did see one such death: the guy was driving over 100 mph and had a head-on crash with a semi going 60 mph. The car actually embedded itself into the engine compartment of the truck. Even so, the aorta was only partly torn (but enough to cause rapid death). In most auto collisions, aortal tearing is not a factor. Modern autos crumple at impact, and the engines break away downward so the cars ride over them. Both actions lessen the impact transmitted to the passenger compartment. Shoulder harnesses lessen deceleration because they stretch a bit. Air bags also reduce deceleration body trauma (though they are primarily designed to keep you from diving into the windshield).

Children are less susceptible to aortic shear tears than adults because children’s arteries are more plastic. As our arteries stiffen with age, we become more susceptible to shear injuries. Children do get more deceleration heart bruising, because their hearts aren’t as tightly anchored as adult hearts. Heart bruising doesn’t cause acute deaths, though in rare circumstances heart bruising can cause fatalities days later.

Brandon Berg is correct about the square-cube law and injury. It applies to children but not infants. Infants have such large heads and small bodies that they are highly prone to neck injuries. Plus, their skulls are thin and still partly cartilage, so they are highly prone to head and brain injuries. Toddlers can withstand more injurious force (on a pound-for-pound or square inch-for-square inch basis) than people of any other age.

Mark F

Aug 22 2009 at 8:54pm

Hold on a second, if we assume motor vehicle crashes are not influenced by the installation of child seats, and “Consumer Reports claims that 4 out of 5 seats are installed incorrectly”, if this statistic is roughly the same as it was in 1997, and “in 1997, six out of ten children who were killed in vehicle crashes were not correctly restrained”, then does correctly installing your child seat make them more likely to die??? If correct restraint made them safer wouldn’t you expect more than 8 out of 10 to die in vehicle crashes?

I’m not seriously arguing child seats will kill your kids, but the numbers are odd and amusing.

Zubon

Aug 22 2009 at 10:44pm

I do statistics and evaluation for one of the state highway safety offices, to provide context for the uncited statements that follow.

What you want to check is A-level (incapacitating) injuries, or better yet the MAIS level, not fatalities. As Levitt and Dubner say, the fatality effect is small, with the main benefit being having kids in the back seat (and adults had greater gains from being in the back seat).

The belt should be enough to keep the kid alive, if that is possible. The booster seat or child restraint may help a little there at the margins, but its main effect is to reduce injury severity. Considering booster seats, the belt rides on the neck and abdomen of a small child, rather than on the hips and shoulder. The kid will not fly around (or out of) the car in the event of a crash, but the damage to the soft tissues in the abdomen can be ugly.

To go back to the original question, the marginal benefit is primarily injury reduction or prevention, not fatality prevention, so you have the wrong metric. Unfortunately, you will need to look at state-level data, because the federal statistics collect only fatalities. This is probably why Levitt and Dubner looked at fatalities rather than injuries: the data is there to see. Checking to see if the child restraints do what they are supposed to requires gathering other data.

David

Aug 23 2009 at 6:42pm

Here’s a question—what fraction of auto fatalities have at least one participant driver who is not allowed to be driving a car for a non-transient reason? e.g.

Has a suspended or nonexistent license or

Doesn’t have auto insurance or

Isn’t a legal resident of the US

Perhaps better enforcing these rules could give us a more economical dollars spent for lives saved ratio?

The Cupboard Is Bare

Aug 24 2009 at 11:31am

“3. Safety improved about as much for older kids (who usually just use seat belts) as it did for younger kids. So there must be many reasons why car travel is safer than it used to be; car seats can’t be more than one piece of the puzzle.”

As someone who grew up during the 50’s and 60’s, I can assure you that neither I nor any of my friends wore seat belts. As a matter of fact, some families were so large, that it was not uncommon to see children sitting on each other’s laps as they were being driven to and from the movies.

As for car seats. When I babysit, I install my neighbors’ car seats in my vehicle. It’s a little tough on the back when you’re trying to install the carseat on the back seat of a tiny sports coupe, but it can be done. I think there are a number of benefits to car seats for things other than the prevention of injuries from car accidents. First of all, if you have to stop short, the child doesn’t end up on the floor stuck between the front and back seats. Secondly, you can keep tabs on what they’re doing at all times. Finally, I find that the design of the seats are such that they seem to provide the kind of comfort children need to fall off to sleep easily.

Tre Jones

Aug 26 2009 at 5:36pm

Doesn’t this analysis only make sense if you are comparing per-miles-ridden data? I’m guessing there are differences in childhood car ridership for a child in the ’50s versus ’00s.

Comments are closed.