My friend and former student Eli Dourado has gotten a lot of attention for his recent post, “The Short-Run Is Short.” Key passage:

Around 40 percent of the unemployed have been unemployed for six months

or longer. And the mean duration of unemployment is even longer, around

40 weeks, which means that the distribution has a high-duration tail.Now, do you mean to tell me that four years into the recession, for

people who have been unemployed for six months, a year, or even longer,

that their wage demands are sticky? This seems implausible.

What Eli doesn’t seem to consider, though, is the possibility of long-run unemployment when inflation is low. Akerlof, Dickens, and Perry’s “The Macroeconomics of Low Inflation” made a very strong case for this back in 1996. The last four years have strongly vindicated their position. Their key point: Firms are heterogeneous, so even when most firms are doing fine, a minority need to cut real wages. With modest inflation, these firms can cut real wages covertly via inflation. With low inflation, firms either have to cut nominal wages and incur workers’ wrath, or cut employment.

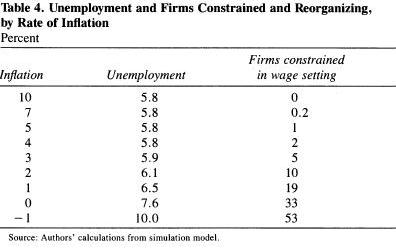

Akerlof, Dickens, and Perry’s paper is complex, but here are the results from a simple simulation. This table shows the fraction of firms that can only cut real wages by cutting nominal wages:

The result is a long-run inflation-unemployment trade-off at low inflation:

[T]he main problem isn’t that unemployed workers are “stubborn” about

their nominal wages. The crucial “behavioral postulates” are rather

that:1. Hiring new workers for lower wages provokes resentment and resistance from existing employees – the classic insider-outsider mechanism.

2.

At this point, the unemployed will probably say “yes” to jobs even if

they they perceive their nominal wages as “unfair.” But after a brief

honeymoon period, these new workers would probably have low morale.

This wouldn’t just hurt their productivity; it would also bring down the

productivity of their better-paid co-workers.

One further point: If the marginal value product of low-skilled workers is falling as rapidly as Eli says, the Akerlof-Dickens-Perry story has added force. Even if most of the economy is doing fine, low-skilled real wages need to steadily fall if low-skilled workers are going to remain profitable to employ. With low inflation, maintaining this steady fall is like pulling teeth, year after year. The facts Eli points to are just what you’d expect to see in an Akerlof-Dickens-Perry world with Dourado-type polarization of labor productivity.

READER COMMENTS

Tyler Cowen

Sep 19 2012 at 9:03pm

Nominal gdp is now above pre-crash peak by a few percentage points, and labor force participation is more or less flat, so squeezing in these workers should be doable, yes?

John Thacker

Sep 20 2012 at 1:10am

Doable, perhaps. I suspect that in the public sector (though not in some states like Virginia) average wages have risen by more than NGDP has risen compared to the pre-crash peak, as well as in other sectors where there have been long term contracts. I suspect that that means that the available NGDP for other workers isn’t necessarily really above the pre-crash peak.

andy

Sep 20 2012 at 2:26am

Thanks for posting this, I always had the same feeling as Eli does.

Why wouldn’t it be profitable to simply create a new firm? You can even create a new branch of a big company, change remunaration schemes, outsource many things and thus eliminate a lot of outsider-insider problem – after all there’s _a lot_ of workers sitting out there with flexibile wage demands. Or is 4 years still too short-term for such changes to occur?

Do we consider the low-productivity unemployed workers (are they all mostly low-productivity, btw?) employable only in settings that disallow such changes to occur?

There were examples even of very big companies cutting wages drastically during this recession. I guess lots of companies could cut variable parts of wages, postpone promotion, cut other benefits, outsource. Is it plausible to consider a 2% difference in inflation making unemployment 5% higher?

david

Sep 20 2012 at 4:48am

@andy

The sticky-wage-problem amongst the remaining employed is a coordination problem; until their wages fall, creating a new firm is unprofitable even at slightly lower wages for the same reason employing the now-unemployed is unprofitable at slightly lower wages.

Bill Dickens

Sep 20 2012 at 5:43am

@Andy and David

Actually new firms do form in this environment (and we had that in our model). Also firms have several ways of circumventing DNWR (for example hiring new workers at somewhat lower wages than their current workers when workers quit or retire (and this too was in our model). Finally, workers are willing to accept wage cuts when a firm is in danger of going bankrupt and costing them their jobs.

So all this would slowly overcome the problem of DNWR in the long run except for the fact that even in times like these average wages are rising due to firm heterogeneity. Even if half the firms are in such bad shape that they aren’t giving wage increases the other half are. I’ve only seen one example where a recession was so bad that almost no one was getting wage increases and nominal wages were falling. That was Finland in the early 90s. Its the combination of downward nominal wage rigidity with the need for some firms to increase wages to quickly expand that keeps unemployment high in the ADP model.

Bill Woolsey

Sep 20 2012 at 8:26am

I don’t agree with theory that hiring new workers at low wages will reduce the morale of existing workers.

I don’t even agree that the new workers will be upset.

People naturally accept the seniority system.

Now, the employers would need to credibly promise to raise these new workers’ pay over time.

This doesn’t require a promise for “equal pay” to to more senior workers. That the senior workers also will be paid more, staying ahead, isn’t a problem. In a way, it is a good thing, showing the new workers that they can expect continual raises over time.

The reason for a long run phillips curve is that some firms that are reducing employment anyway, would reduce it more slowly if they could wages for existing employees. (New employees pay is not an issue.) Because cutting pay reduces morale, this strategy is not followed, and so more workers have to find new jobs. New jobs are being created all the time by new firms and by existing firms that are expanding employment. They can offer lower pay to these workers.

But this added “churn” compared with a situation where more people stayed at their jobs and received lower pay means that the unemployment rate is higher. Even if the wages are at market clearing levels, so there are vacancies for every unemployed person (and quantity of labor demanded and supplied match,) there are more vacancies and unemployed than in a scenario where people would take pay cuts to keep their current jobs.

As for the current situation, “the problem” is that firms don’t expect it to be permanent. The first best situation is to promise a prompt recovery in spending on output and deliver. The second best is to accept the lower growth path of nominal spending and adjust all prices and wages downward–alot. The worst situation is to promise a prompt recovery in nominal spending and not deliver. Firms are keeping a “nominal” structure of prices and wages that are appropriate if there is a nominal recovery.

Glen Smith

Sep 20 2012 at 10:16am

Bill,

You may not believe that hiring new employees at lower wages hurt morale of existing employees, but I’ve witnessed more situations where hiring new employees at lower wages hurt the morale of the old employees and never witnessed the reverse.

Costard

Sep 20 2012 at 12:21pm

If existing businesses would rather lose money than upset the “equilibrium” of the workplace, then we’re looking at an opportunity for startups. This on top of the incentives already in place for the unemployed to find a way to employ themselves, and the general truism that younger and smaller enterprises are better able to adapt to a changin environment.

So shouldn’t any discussion of persistent unemployment address the difficulty of starting a new business? The regulatory environment has shifted under the current administration – to put it mildly – and ZIRP favors larger companies with less risk (and greater subsidies), whatever securities the Fed is buying, and sure-fire arbitrage opportunies like IROR. The odds of succes for a small business in this environment are low and rates do not justify a loan to one. Have we ever witnessed such a spread between risk and risk premium?

Can we discuss the role of monetary stimulus in reducing the impetus for job formation? Or as Bill said, the role of deflation in forcing an adjustment and, I would add, bringing real interest rates to a point that favors some actual risk-taking?

andy

Sep 20 2012 at 1:44pm

Thanks for the answer. Still…I know I should probably read the paper (and I am downloading it right now, maybe I will answer my question when I read it..), but…

“run except for the fact that even in times like these average wages are rising due to firm heterogeneity”

“Its the combination of downward nominal wage rigidity with the need for some firms to increase wages to quickly expand that keeps unemployment high in the ADP model.”

I understand why downward rigidity is a problem. I understand the incentives problem. I don’t understand why the fact, that some firms need to hire workers who are in short supply – thus rising wages, thus maybe rising average wage – causes unemployment?

I hope to find the answer in the paper 🙂

Mr. Econotarian

Sep 20 2012 at 3:59pm

I think the problem in the US is not “sticky wages” but “sticky unemployment benefits”.

If unemployment benefits did not last so long, I suspect many unemployed would quickly adjust to new lower wages, potentially by moving into new fields of work.

andy

Sep 20 2012 at 4:43pm

Ok, I think I understand – is there the idea that some firms will raise wages because of a temporary scarcity of workers – and later, when the markets calm, they won’t be able to lower the wages.

I don’t know. Shouldn’t we expect enterpreneours to know better?

@david

The sticky-wage-problem amongst the remaining employed is a coordination problem; until their wages fall, creating a new firm is unprofitable even at slightly lower wages for the same reason employing the now-unemployed is unprofitable at slightly lower wages

Why? Isn’t it the same as claiming that a discriminating monopoly won’t sell for slightly more than MC because they already sold to some customers for twice the MC?

Chris H

Sep 21 2012 at 1:01am

An interesting article, but I do have a bit of a bone to pick with the morale lowering issue. I won’t deny that it can be a real concern, but I think you need more than that to show how it leads to unemployment issues this persistent.

The main issue I have is why this morale attacking effect can’t be priced into the new workers’ wages? The morale problem seems to me to be more based on the existence of a wage lowering of the new workers rather than necessarily the degree of that lowering. It could very well be that a 10% wage cut for new workers has similar effect on morale of existing workers as a 25% wage cut (the existing workers aren’t the ones with the lowered wages after all). However, that difference in wages could very well be the difference between the worker being worth while to hire with this morale dampening effect or not. Now it could be that there are other limitations on how far you can cut these wages. The minimum wage is one of these of course, which if that was blocking a market clearing price for some wages we’d expect people who likely have lower productivity have higher unemployment. A lower education is one of the best predictors for that especially below college entrance and thus we’d expect high school dropouts and high school graduates to have higher unemployment. Low and behold, that is the case: http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_chart_001.htm

This point also works with unemployment insurance which should tend to tempt those who already would be making low wages more than those who make more (as the difference in income would be greater for those who’d tend to make more) to remain unemployed and hold out for higher wages.

Both of these cases however are arguments for removing laws and entitlements rather than QE3.

Now as for the inflation as solution argument, have you taken into account the degree to which workers do recognize the difference between nominal and real wages? While I readily admit the average store clerk or doctors office secretary probably doesn’t have a great grasp of the concepts of QE3 or market clearing wages, they can recognize when it costs more to buy all the food for the week or to get new clothes. They’ll feel the extra squeeze that’s been put on and can adjust wage demands accordingly. If the increase in wage demands do not remain below the increase in inflation don’t we enter a situation where inflation loses it’s ability to reduce unemployment?

Forgive me if that is a complaint that’s been dealt with before in other similar topics, but I’m new to the blog.

Jim Glass

Sep 21 2012 at 6:34pm

I don’t understand why the “sticky wages” issue is so hard to understand. We have obvious examples of it in action all around us.

Take a labor union whose members are asked to vote on the proposition: “To save all our jobs we can all take a 5% pay cut, or else we can keep all our pay and just lay off the 5% most junior of us.” This happens all the time — and the vote is near always “We keep our pay, goodbye to you junior 5%” by a typical vote of 95-5.

The union mechanism makes it more visible to the naked eye, by the same incentives and pressures exist in non-union work forces.

Try to force an across-the-board pay cut on a non-union workforce and morale will be hammered with the *first* employees to bolt to the competition or to other opportunities will be your *best* employees, among many other unhappy consequences.

I don’t agree with theory that hiring new workers at low wages will reduce the morale of existing workers. I don’t even agree that the new workers will be upset.

Oh, I’ve got a career as an entrepreneurial employer and you are simply *wrong* about that.

Try hiring different people to do the same job and tell them publicly to their faces: “Yes you are doing the same job at the same quality, the very same thing, but I am paying you all very differently, you guys here are getting *30% less* than them for no reason other than that’s all I’m going to pay you, tough, lump it, deal with it.”

You will be lucky if they deal with it by quitting and badmouthing you and your business — because if they stay on the results will be toxic among *both* the high-paid and low-paid workers.

People naturally accept the seniority system.

Which is why the junior workers get fired — or don’t get hired, which amounts to the same thing.

GinSlinger

Sep 22 2012 at 9:16am

Try hiring different people to do the same job and tell them publicly to their faces: “Yes you are doing the same job at the same quality, the very same thing, but I am paying you all very differently, you guys here are getting *30% less* than them for no reason other than that’s all I’m going to pay you, tough, lump it, deal with it.”

Do you not give annual raises/increases? Or, do new hires actually get the same salary/wages as someone who you’ve employed for 20 years? Either of those I could see causing a lot of morality reduction.

J.V. Dubois

Sep 24 2012 at 8:37am

GinSinger: you are changing the point of the excercise. Imagine that you have two people: one is your internal employee with 15 year experience in a field out of which he spent 5 years in your company. He is considered senior.

Then you have candidate who is equally capable with 15 years experience in the field. He does not know exactly how it “works” within the company, but that could actually be a boon.

It is of course normal to announce that you will hire him with a somewhat lover salary for probation period (let’s say 3 months) and after that you will sign a 1 year contract for somewhat lower paycheck. But then, if the person learned all there is with regard to internal specifics in a company he should be considered an equal to anyone of your internal employees with the same ammount of experience. If he does not, you are either doing cutting-edge research or reevaluate your internal training programme.

So to make it simple: if you have two persons in a company who do about the same ammount of work with about the same ammount of quality, you cannot maintain any significant salary difference and not suffer morale deterioration. It is entirely possible that the new hire will slack his work so that he “earns” the salary he actually gets, but then you did not get anywhere. Your costs per output are the same as before and you are still in trouble.

But most of the time this just causes destructive spiral as other people see that thay can “buy” slacking with somewhat lower performance, that lower performance is tolerated. Givent that there are only rare situations when business owner has 100% control over the ammount of effort that was put into work of his employees, this leads to general fall in productivity and much worse outcome.

Bill Woolsey

Sep 25 2012 at 9:27am

Glass:

I think sticky wages and prices are serious problems.

I don’t agree that lowering the starting pay of new workers causing poor morale for anyone is a problem.

Cutting pay for existing workers is a problem.

In real labor markets, the choice isn’t cut everyone’s pay 5% or lay off 5% of the workers.

It is, continue to raise everyones pay by 3% on average, and hire many fewer new workers, so that production fails to grow like usual or even shrinks as total employment shrinks due to attrition, or else, give up part or all of the wage increase, or many even go so far as to cut wages, so that the total employment at the firm will shrink less or even grow, in the limit as much as usual (or more, I guess.)

I think the usual approach is cut back net new hires, reduce employment by allowing attrition, reduce pay increases, no pay increases.

Only then to we get to the choice of layoffs or pay cuts.

Anyway, at stop one, fewer new hires, we start getting growing unemployment. The labor force is growing.

Then, when we get to attrition, that is greatly reduced from normal levels because people quit less.

It seems to me we are in an “equilibrium” where firms are giving slighly lower pay increases, and are hiring much less, quits are low, so there is less attrition than usual.

Starting pay is being reduced. That may be a key reason why average pay rates are growing slightly less.

What “should” happen is that the unemployed workers undercut the wages of the employed. The firms tell their current employees to take pay cuts, or be replaced. The current employees have to suck it up because they don’t want to quit. No job opportunties else where. (Quits are rate, duh.)

That is the break down. The firms aren’t telling their current employees they have to take pay cuts, because they have no option. They can’t quit because they have no good alternatives.

I think the reason firms don’t do this is that they expect this entire situation to be reversed before too long. And so, they would be making temporary profits until either other firms copied them or else nominal expenditure recovers. In the scenario where other firms don’t copy them, it is likely that they will be considered “bad” employers and so the strategy fails. If all the other firms did it too, that wouldn’t be a problem.

Of course, for employment and production to be maintained with the spending decrease we had, an immediate cut in prices and wages would have been needed.

By now, we would be close to equilibrium if they had just immediately gone with no pay increases.

But instead, they go with no new hiring and continue to with pay increases.

The least bad solution in my opinion is to generate the nominal recovery that firms expect will happen sooner or later.

Comments are closed.