I’m currently polishing up my behavioral health economics book The Seven Deadly Sins. The first five chapters discuss the core health concerns of diet, exercise, drinking, smoking, and sex. The last two “sins” are using heroin and climbing Everest. I included these chapters for the sake of entertainment; I doubt many of my readers will be weighing the pros and cons of engaging in these activities. However, I discovered that these two ways of getting sky high could be used to illustrate a lot of important economic principles.

Here is a short excerpt from the chapter on Everest.

Why do people climb Everest? One possibility is that they seek a little fresh air and wish to enjoy the great outdoors. This seems doubtful. Alternatively, people might climb Everest out of pride or as a way of gaining status. Evidence for the status-seeking theory can be seen by looking at what peaks are climbed in the Himalayas. All things being equal, going higher means increased risk and physical suffering. However, the climbs that garner the greatest prestige are the fourteen peaks that are higher than eight thousand meters. If status is important, then climbing mountains just over 8000 meters will be much more desirable than climbing mountains just under 8000 meters. Even if the peaks just under 8000 meters are similar in deadliness, there is no simple shorthand way to communicate your achievement.

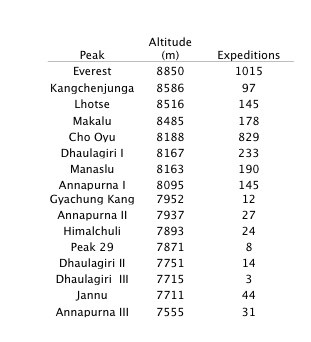

Elizabeth Hawley has been cataloging Himalayan expeditions for decades; her data is as close as there is to an official record. Her records provide information about eight of the fourteen peaks higher than 8000 meters. (She doesn’t concern herself with the peaks in the Karakoram nor does she disclose data for Shingapanga which is completely in China.) I’ve extracted the following chart from Hawley’s dataset. It shows the sixteen highest peaks in her data: eight above and eight below the 8000 meter threshold.

The drop off in expeditions at the arbitrary cutoff of 8000 meters is striking. In fact, every peak over 8000 meters has more expeditions than any of the eight peaks just below 8000 meters. In the chart, there are two obvious outliers with the most expeditions: Everest and Cho Oyu. The appeal of Everest is obvious; climbing the highest peak in the world confers a type of status that is universally recognized. Cho Oyu’s popularity can also be explained by status seeking. It is generally considered the easiest of the eight-thousanders to climb.

If high-altitude mountaineering had been pioneered by Americans instead of Europeans, would the arbitrary threshold have been set in feet? If the artificial bar for acquiring glory had been set higher than Annapurna I, many fewer people would be tempted to climb what is considered by many to be the deadliest of the eight-thousanders. Alternatively, the bar could have been set lower and many more climbers would have scaled the rather obscure Gyachung Kang. In another alternate world, alpinists would brag about climbing the world’s 10 highest peaks; a distinction never mentioned in my readings. (The arbitrary cutoff of the 8000 meter peaks finds a parallel in modern long distance running. There are a great many races that are 26.2 miles long, but not races that are, for example, 25.8 miles long. The first few marathons had varied distances before the length became standardized. A long run with an unspecified distance could never confer the same status as a marathon.)

To the extent that climbing Everest is primarily motivated by status, it might be wasted effort from a social standpoint. Status is by its nature a positional good; someone who gains status by climbing Everest likely detracts from the status of lesser achievements such as marathon running.

READER COMMENTS

Shane L

Feb 12 2014 at 5:10am

Nice bit of thinking about it, I enjoyed that!

I’d add, though, that there might be more to it than just status. I can imagine an individual feeling an important sense of accomplishment, or even some kind of spiritual connection with the earth, in climbing Everest and knowing that this is the highest point on the planet. Supposing someone was going to climb a major mountain, but nobody else would ever hear about it. Would he or she be content with a lower peak? I suspect many would still yearn to reach Everest, even if they could expect no extra status for the achievement.

DougT

Feb 12 2014 at 5:12am

I’m so disillusioned! “Because it is there” had been seared into my memory forever. Now Mallory and Hillary are just the same as status-seeking politicians and bloggers. Bummer.

James Schneider

Feb 12 2014 at 5:21am

@ Shane L I agree.

In a strange way, I think these arbitrary designations can make it easier to communicate our achievements to ourselves. For example, if you ran 25miles did you “quit” when you got tired? But running a marathon proves to yourself that you’ve reached a goal.

Shane L

Feb 12 2014 at 9:35am

Good point, James. Goals already set in the past, however arbitrary, can become convenient targets for us. (A Catholic trying to live with a more healthy diet, or without smoking, might find the pre-ordained structure of Lent handy as a target for his or her own goals.)

blink

Feb 12 2014 at 9:43am

Fun points to consider; you make a strong case for signaling with Everest. It would be interesting to test your change-of-units story. If Americans set the bar, it would probably 25,000 feet — between Jannu and Annapurna III.

I am less convinced that 26.2 is due to signaling; it is simply focal. By comparison, there are good reasons that McDonalds has a “Dollar menu” in the US, but it would not make sense elsewhere.

RPLong

Feb 12 2014 at 10:06am

DougT makes an important point. Schneider writes, “…out of pride or as a way of gaining status,” and then spends the rest of the post discussing status. To be sure, some who climb Everest do so for status, but we can’t ignore pride, AKA a sense of accomplishment.

I can’t help but conclude that Schneider does not climb many mountains or run many marathons. We run marathons because there is a great folklore story that goes with it. I wouldn’t run a 25-mile race because it takes exactly the same amount of race preparation and effort, and race organization, and everything else… but then you lose out on the folklore. And what is this folklore, nothing more than status? Or is it being a part of a great human tradition, testing our limits, and seeing whether we can rise to the occasion? Is there value in romance, or is it all just status-seeking?

Finch

Feb 12 2014 at 10:16am

> I am less convinced that 26.2 is due to signaling

“No one would run marathons if you had to sign a confidentiality agreement first.”

– traditional saying

Daniel Kuehn

Feb 12 2014 at 11:34am

DougT – But that’s not the point. You climb “because it’s there”. The question is, in selecting your peaks why do you select what you select?

Everest is a superlative. That’s why it has over ten times as many climbers as the next highest peak. But people climb more than just Everest. What determines what they climb other than Everest? Clearly not height because there is a discontinuity in climbing that you don’t observe in height.

Is there another explanation for the discontinuity besides the nice round number of 8,000 that lots of people have fixated on? Perhaps there’s another explanation, but none come to mind.

This is evidence that status matters. There is no claim I can discern in the post that nothing else matters.

Pajser

Feb 12 2014 at 11:37am

The scientist who publish anonymously doesn’t improve his status but he doubles his sense of accomplishment: as an author and one who overcame the vanity. Conclude for yourself.

Blakeney

Feb 12 2014 at 11:47am

Actually, I don’t think it would have made any difference. It just so happens that the 8km cutoff in your list (between Gyachung Kang and Annapurna I) corresponds to a 5-mile cutoff in English measurement:

Alex Godofsky

Feb 12 2014 at 12:23pm

This is ridiculous. Pride/status/prestige are society’s tools for promoting virtuous behavior.

If a health insurer gave a rate cut for exercising and eating healthily, would you deride its customers for just doing it for the money and not really caring about their health?

RPLong

Feb 12 2014 at 12:25pm

@ Daniel Kuehn

Can you explain how simply observing which peaks were selected answers this question?

Daniel Kuehn

Feb 12 2014 at 12:35pm

RPLong –

re: “Can you explain how simply observing which peaks were selected answers this question?”

See the rest of the comment.

There’s presumably lots of reasons why peaks are chosen. But revealed preference often gives us clues about the structure of preferences. If the only thing different between otherwise similar peaks is that they are above or below an otherwise arbitrary threshold, it’s reasonable to infer that threshold is significant.

Of course James gave another reason that you wouldn’t know about just by looking at the heights. It’s of course a complex story, but revealed preference should inform how you think about it.

Daniel Kuehn

Feb 12 2014 at 12:38pm

Agree with Alex Godofsky. I wouldn’t be very hard on status or even just apparently arbitrary choices. There is a possibility that it’s a wasted effort from a social standpoint for the reasons stated, but only a possibility.

Granted, I wouldn’t be too hard on James either. I assume that’s why he said “might be wasted effort”.

Aaron Zierman

Feb 12 2014 at 12:41pm

@Alex Godofsky

Status here is not claimed as the only factor, but rather it is shown as being a factor.

You said: “If a health insurer gave a rate cut for exercising and eating healthily, would you deride its customers for just doing it for the money and not really caring about their health?”

The incentive of the rate cut might push some from not excercising or eating healthy to being healthy. I don’t think that you’re saying that the incentive of money has no effect, are you? Did they not care about their health before? Well, not enough to do anything about it until the extra incentive arrived.

The same can be said of climbing Everest. A contributing factor in choosing to climb Everest seems to be increased status. Not the only reason, but certainly part of the motivation.

RPLong

Feb 12 2014 at 1:05pm

@ Kuehn (and others)

No, I still feel we have more work to do here. This looks like Curry’s Paradox to me:

If peaks under 8000m are climbed much less frequently than peaks over 8000m…

(If this statement is true…)

…then status is the reason people climb Everest.

(…then Germany borders China.)

No, it simply won’t do to affirm the consequent. If we want to establish that status is the motive for why climbers summit peaks over 8000m more frequently, then establish a link between peak selection and status, not a mere tally of peak selection.

There is no “revealed preference” here, other than a revealed preference for peaks over 8000m. I don’t dispute that those are the preferred peaks, what I dispute is that status, specifically is the reason they are preferred.

Can anyone substantiate this?

Daniel Kuehn

Feb 12 2014 at 1:13pm

RPLong –

I am inferring that you don’t like making inferences…

If your only point is that neither direct evidence nor a logical proof (presumably we are more interested in the former) has been provided, I don’t think there is a single person here that isn’t aware of that. I also don’t think there is a single person here that claimed direct evidence or logical proof was provided. We are making inferences from persuasive indirect evidence.

If you have another point then I might be missing it.

Daniel Kuehn

Feb 12 2014 at 1:22pm

RPLong –

As for Curry’s paradox, I think you’re trying too hard. I’m no logician, but as far as I can tell the problem with Curry’s paradox is that it is self-referencing. That doesn’t even come into play here. What James is referencing is a variety of intuitions, experiences that we have with human motivation, knowledge we have about the significance of round numbers, etc. I don’t see where the problems of Curry’s paradox come into play at all.

Daniel Kuehn

Feb 12 2014 at 1:38pm

RPLong –

Ya the more I think about it I have no idea why you’re bringing up Curry’s paradox. Could you explain a little more?

The way the first half is constructed the sentence has to be true. That’s the whole point. The way your first half (“If peaks under 8000m are climbed much less frequently than peaks over 8000m”) is constructed in no way guarantees the sentence is true. So what’s the tie-in?

I don’t want to get too far afield. I don’t think you should be thinking in terms of logic when what we’re doing is musing on whether indirect evidence is persuasive. No one is suggesting that a proof has been offered. But given that you wanted to go down that road I don’t really understand how your argument makes sense.

RPLong

Feb 12 2014 at 2:01pm

Kuehn – No need to draw inferences from data points that have voices.

— Sean Burch, Hyperfitness

That’s why people climb 8000m peaks. Maybe you’re right that fixating on the logical shortcomings of the analysis was the wrong way to make my point. But when something is neither logically consistent, nor consistent with the reasons people actually say they run marathons or climb mountains, it’s time to check your premises. This would be more obvious if you had run a marathon or something. I highly recommend you read the first two chapters of Hyperfitness. It might not change your life, but it’s inspiring nonetheless, and a great exposition on why people like to rise to challenges.

Daniel Kuehn

Feb 12 2014 at 2:16pm

RPLong –

You seem to be thinking that I am disputing what you’ve written there. I’m not clear why. It’s a little off subject, no? We were discussing whether status plays a part in these decisions, not whether other factors do.

I have not run a marathon. I do know why sought out the challenge of rowing crew, or why I sought out the challenge of a PhD program. I am sure it’s great reading but I think I will take a pass on Hyperfitness for now particularly as it seems to confirm what I already think is an important part of why people embrace challenges.

Daniel Kuehn

Feb 12 2014 at 2:19pm

RPLong –

re: “Maybe you’re right that fixating on the logical shortcomings of the analysis was the wrong way to make my point.”

Just to be clear, that was not my point. If there are logical shortcomings, by all means fixate on them. I don’t think that’s what you were doing and I think in fact there were big problems with your logic.

RPLong

Feb 12 2014 at 4:39pm

Okay, Kuehn, here’s my last attempt:

1. My first comment was an assertion that status plays a rather minimal role in peak selection.

2. My second comment was a rhetorical question designed to help you see that simply tallying summit counts says nothing about status motives.

3. My third comment highlights the logical problems of affirming the consequent in a stand-alone if-then logical statement. I further added: “I don’t dispute that those are the preferred peaks, what I dispute is that status, specifically is the reason they are preferred.”

4. My fourth comment provides a specific example highlighting the fact that status plays a minimal role in the decision to summit tall mountains.

Either I am pretty close to right, or I am embarrassingly wrong. Either way, I probably won’t get any more right or wrong with additional comments, so I’ll leave it at that.

I will end, though, by saying that I think Schneider’s main point is that Everest summits offer a good opportunity to demonstrate economic principles, and I think he’s absolutely right about that. And I think that I probably owe him an apology for getting caught on a tangent, so here it is: I am genuinely sorry. That was dumb of me.

Steve Sailer

Feb 12 2014 at 5:38pm

Where’s K2, the second highest peak at 8611 meters and widely believed the hardest? It’s also extremely inconvenient merely to get to the base.

I’m not just niggling, but I want to raise a general point of there being different spheres of status. Climbing Everest would give you higher status in, say, your alumni newsletter, while climbing K2 would give you higher status within the small community of dedicated mountaineers.

James Schneider

Feb 12 2014 at 6:00pm

@Steve K2 is not in Hawley’s data because it is one of the 8000ers that is in the Karakoram. Ideally, I would have data on all 14 8000ers and then the 14 peaks below 8000.

I’m pretty confident that doing the above and below 8000 meters would be even more impressive if you just looked at the Karakoram peaks in isolation (if the data were available). Quite a few elite climbers go to the Karakoram to climb the 8000 peaks (since climbing as many 8000ers as possible is a recognized goal). I don’t remember reading about people going to the Karakoram for general hiking or to climb a peak less than 8000 meters.

Andrew

Feb 12 2014 at 10:21pm

I think there must also be an element of path-dependence to this (pun intended). Once a peak becomes marginally more popular, experienced mountaineers are more likely to return to lead others to the top. Moreover, indigenous guides would make themselves available where demand is strongest, and keep to those peaks they know best. Wouldn’t climbers be less likely to attempt peaks where fewer guides are available?

Steve Sailer

Feb 13 2014 at 1:14pm

There is an enormous literature by climbers, probably the largest for any sport by the sportsmen themselves. And they are not inarticulate on their own motivations, which can be multi-dimensional.

James Schneider

Feb 13 2014 at 4:56pm

@Andrew

Wouldn’t climbers be less likely to attempt peaks where fewer guides are available?

This is definitely the case with Everest and Cho Oyu the two peaks on the list with an organized guide industry.

I think the other peaks are rarely if ever attempted by anyone other than elite mountain climbers.

Comments are closed.