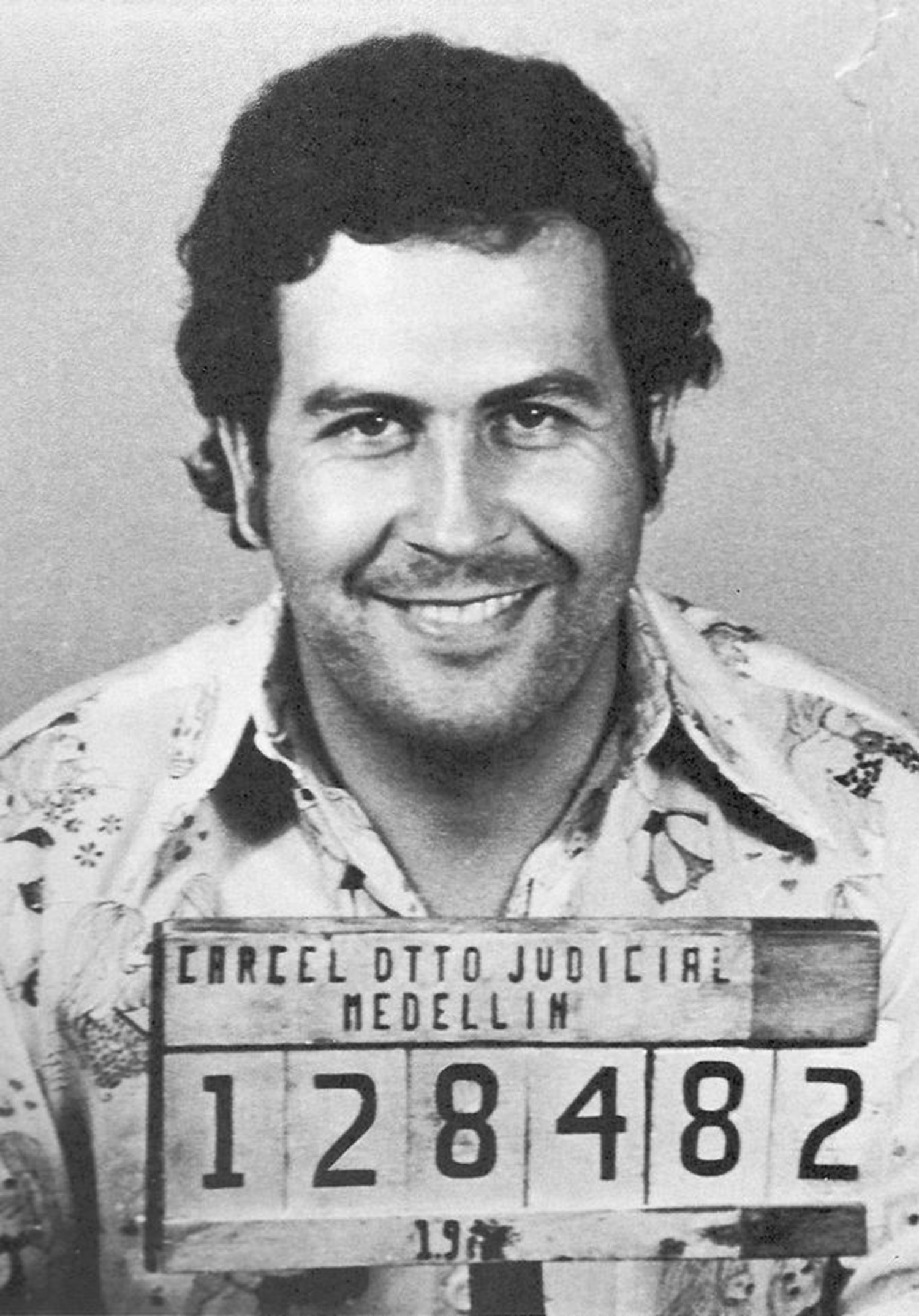

While vacationing in LA, I saw Escobar: Paradise Lost. Not great, not bad, but I did learn something: drug lord Pablo Escobar was beloved as well as infamous. His massive charitable giving won him a mass following: About 25,000 people attended his funeral, and his grave continues to attract admirers. Escobar’s ardent fans don’t deny that he murdered hundreds or thousands. But they think his philanthropy far outshines whatever he did to earn his riches. A fascinating unpublished paper, “Robin Hood or Villain: The Social Constructions of Pablo Escobar” explores the tension:

Pablo Escobar was a Colombian drug lord and leader of the Medellín Cartel which at one point controlled as much as 80% of the international cocaine trade. He is famous for waging war against the Colombian government in his campaign to outlaw extradition of criminals to the United State and ordering the assassination of countless individuals, including police officers, journalists, and high ranking officials and politicians. He is also well known for investing large sums of his fortune in charitable public works, including the construction of schools, sports fields and housing developments for the urban poor. While U.S. and Colombian officials have portrayed Escobar as a villain and terrorist who held the entire nation hostage, many people among the Colombian popular class admire him as a generous benefactor, like a Colombian Robin Hood.

Furthermore:

Pablo Escobar’s most famous personality traits were his extreme ruthlessness and his great generosity, as attributed to him by his enemies and admirers, respectively. Each of these traits has some evidence to support it. It is unclear exactly how many murders can be attributed to him because he employed numerous sicarios (assassins) to carry out his orders for him and was always careful to avoid anything that would directly link him to the crime. However, he and his associates were probably responsible for hundreds, if not thousands, of deaths, including police officers, journalists, and high-ranking officials and politicians. He also funded social programs and housing projects to benefit the poor, such as Barrio Pablo Escobar as it is called today, a neighborhood he had constructed in Medellín to house the poor living in the city’s dump that still has nearly 13,000 residents. There he is still remembered as a great man and referred to as “Don Pablo”. It was Semana magazine in 1983 that first described him as a “paisa Robin Hood,” praising his charity work.

You could minimize all this as a sign of Colombians’ depravity, but you probably shouldn’t. Human beings deeply admire philanthropists. It brings tears to our eyes to see a rich man share his bounty with widows and orphans. Once the tears start, objectivity ends. If the philanthropist has feet of clay, we yearn to show him leniency, to give him the benefit of the doubt.

Even if he’s a mass murderer, a strong record of charitable giving makes us want to call him “complex” rather than wicked. The families of the slain will never love him, but their neighbors will rush to excuse his “excesses.” And his cheerleaders will hardly be limited to the direct beneficiaries of his largesse: Charity melts the hearts of witnesses as well as recipients.

You could of course object, “Escobar wasn’t really charitable. The money he handed out was never his in the first place. He extorted and stole his ‘donations’ from others.” But my point is about moral psychology, not moral philosophy: Even “fake” charity inspires affection.

So what? Libertarians often argue that welfare states, like Pablo Escobar, are not really “charitable.” Whether or not they’re right, the fact remains: Welfare states seem charitable to almost everyone. School-lunch and old-age programs inspire the same emotions as uncontested charity: Admiration, affection, gratitude. And these emotions have the Escobarian downside: They melt people’s consciences, leading them to excuse and minimize the most horrible of crimes.

This doesn’t mean we should lament Bill Gates’ philanthropy because it will lead jurors to show leniency on the off-chance that he commits a murder. For a nice guy like Gates, this is a small downside. But when organizations that kill people for a living – like crime families or governments – loudly help the needy, we should indeed shudder. Why? Because their perceived philanthropy makes it easy for them to get away with murder. Maybe they’ll use their power over life and death wisely and fairly. But they probably won’t – especially if they’re surrounded by devoted fans eager to excuse their… shortcomings.

READER COMMENTS

david

Jul 7 2015 at 9:19pm

like Robin Hood, for Robin Hood to be heroic, both the governing authority (Prince John) and their local enforcers (the Sheriff) must be illegitimate. Prince John is illegitimate because he schemes against the rightful King Richard, away on crusade. The Sheriff is illegitimate because he abuses his power.

Pablo Escobar can be rendered a hero because the government in Colombia has weak legitimacy; the money Escobar handed out wasn’t his, but it often also wasn’t those he stole from, at least in the eyes of Escobar’s fans

legitimization precedes property rights, not the other way around

KLO

Jul 7 2015 at 9:22pm

George Mason owned a very large number of human beings. He knew it was very wrong. They named a university after him. You may have heard of it.

People cannot but overlook the moral failings of their heroes.

JLV

Jul 7 2015 at 10:53pm

The last paragraph is empirically testable, but anyone care to bet whether Caplan would update his priors if welfare states were less violent?

Pajser

Jul 7 2015 at 11:48pm

It is maybe opposite – moral behaviour of the nation in one area maybe causes increased expectations that it should behave morally in other areas. Maybe, after one problem is solved (“poor Americans”) active people tend to pick other problem to solve (“poor Africans.”)

Mike H

Jul 8 2015 at 2:10am

JLV,

Perhaps a welfare state can become less violent, but can it become non-violent? Their charity requires theft. And theft is an inherently violent crime.

Pajser

Jul 8 2015 at 5:42am

Mike H. Property is violent, redistribution of property is not violent. You have TV, that means I cannot use it without your approval. And if I try, people with big guns will come after me. I didn’t started violence, they did. I only want to watch TV. What redistribution means? That people with big guns will be against you and not against me. Amount of violence in the system is exactly the same. Only its direction changes.

Granite26

Jul 8 2015 at 7:26am

I’ve seen the opposite scenario as well…people who did undeniably horrible things having their lesser positive achievements and contributions…black washed?

‘oh no, we can’t credit them as being part of that…they were a Nazi’ in reference to the space program, at least.

guthrie

Jul 8 2015 at 1:56pm

Granite26 has a point. This can be a two way street.

At what point or under what circumstances do the ‘credits’ and ‘debits’ of an individual or organization ‘balance’ or tip? Would people be as charitable toward Escobar if he set out to slaughter Jewish people (as opposed to the list of innocents posted above)? Hitler and Lenin both have a lot of innocent blood on their hands, yet who is more reviled?

ThomasH

Jul 8 2015 at 2:47pm

While even one admirer of Pablo is one too many, admirers were a minuscule part of the Colombian public and I’d argue that the admiration such as it was did little to make it easier for him to get away with his crimes.

Jacob Aaron Geller

Jul 10 2015 at 11:41pm

Granite’s comment reminds me of the fact that Bill Cosby’s standup and sitcom have suddenly vanished from cable.

The police definitely get away with a lot of awful things, by fighting crime… Or, Granite might say, they don’t get enough credit for fighting crime, because of all the awful things they do.

Comments are closed.