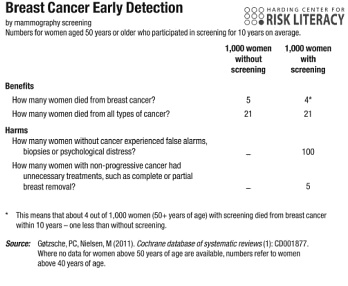

Gigerenzer’s Risk Savvy also presents transparent statistical evidence against routine mammograms. The presentation slightly changes, relying on a “fact box” rather than an icon box. But the idea remains the same: Clearly summarize outcome frequencies from women randomly assigned to either screening or no screening. Results:

At first glance, screenings save the life of one women in a thousand. On closer look, however, screenings only alter the kind of cancer that kills you, not overall cancer mortality. Whether they’re screened or not, 21-in-1000 women died of cancer within ten years.

Details on the benefits:

First, is there evidence that mammography screening reduces my chance of dying from breast cancer? The answer is yes. Out of every one thousand women who did not participate in screening, about five died of breast cancer, while this number was four for those who participated. In statistical terms that is an absolute risk reduction of one in one thousand. But if you find this information in a newspaper or brochure, it is almost always presented as a “20 percent risk reduction” or more.

Second, is there evidence that mammography screening reduces my chance of dying from any kind of cancer, including breast cancer? The answer is no…

In plain words, there is no evidence that mammography saves lives. One less women in a thousand dies with the diagnosis breast cancer, but one more dies with another cancer diagnosis. Some women die with two or three different cancers, where it’s not always clear which of these caused death.

Details on the costs:

First, women who do not have breast cancer can experience false alarms and unnecessary biopsies. This happened to about a hundred out of every thousand women who participated in screening… Second, women who do have breast cancer, but a nonprogressive or slowly growing form that they would never have noticed during their lifetimes, often undergo lumpectomy, mastectomy, toxic chemotherapy, or other interventions that have no benefit for them…

Furthermore, since diagnosis typically leads to treatment, the fact that more-diagnosed women don’t live longer is striking evidence that breast cancer treatments are, on average, ineffective. Hansonian medical skepticism may be overstated, but it is firmly grounded in fact.

READER COMMENTS

Michael Tontchev

Aug 12 2015 at 2:45am

Disclaimer: I know next to nothing on the science of cancer.

My question is: could they just be looking at the wrong time horizon? What if it saves lives 20 or 30 years out?

ThomasH

Aug 12 2015 at 7:36am

The facts presented seem to indicate a problem with the follow up to the screenings.

I notice this is filed under “cost benefit analysis.” has no one tried to conduct one on this or prostate cancer screening?

Pajser

Aug 12 2015 at 7:52am

Gigerenzer: “.. is there evidence that mammography screening reduces my chance of dying from any kind of cancer, including breast cancer? The answer is no…”

Maybe his “21” is 20.5 in one case and 21.4 in other. Beside already discussed objections, there is an improvement of the medical procedures with time. It appears Gigerenzer relies on Gøtzsche & Nielsen, 2011. Current version of that article analyzes eight trials, the earliest one 1963-67, the last one 1991-97, i.e. data seems to be relatively old.

dnagamoose

Aug 12 2015 at 8:21am

While I’m sympathetic to the data, I have one question I’d want cleared up before I tried to convince anyone not to get screening exams from these charts.

For the prostate screening, he generalizes from death from the specific cancer to all deaths. For the mammogram, he generalizes to all cancer deaths. Does he describe in the book the reason for this difference?

I can easily see it being just a result of using whatever data was available for each kind of screening, but it at least opens the possibility of cherry picking the data to make the argument.

Trevor H

Aug 12 2015 at 8:21am

I’ll share with you a little of my wife’s breast cancer story.

First, her cancer was discovered by a “hands-on” exam by her ob-gyn despite multiple prior mammograms. And fortunately she insisted on a full double mastectomy – the surgical biopsy revealed 5 cm of tumors in both breasts that had not been detected even by the more extensive imaging done prior to surgery.

As for adjuvant treatment, the recommendations we had from multiple oncologist ranged from – “just do the chemo” to “reduction of recurrence of 50%”. I told them I have a math degree, I can handle the numbers, didn’t matter. I found a website where, after registering as a doctor, I was able to get summary statistics based on the specific characteristics of her cancer. Chemo was indeed good for 50% – from 8% recurrence down to 4%. Considering that chemo itself kills 1 to 2% of patients, it was a straightforward decision to decline.

I still trust doctors for their ability to provide services, but not for decision-making. Just give me the data, I’ll make the decisions.

Sol

Aug 12 2015 at 8:36am

Okay, this post helps me put my finger on what I think is wrong with this approach. (I may just be copying the spirit of commenters from the last post, mind you.)

The thing is this: it doesn’t address how long you lived; it only considers whether or not you were dead of cancer in ten years. It would be entirely consistent with these statistics if among those who died of cancer, those who had the screenings on average had five more years of life than those who didn’t. While that arguably might not be that important in the big medical picture, it can be wildly important to those affected by cancer.

(Also unless they’re randomly choosing who gets / does not get screening, we should almost certainly expect that those who get screening have a higher cancer risk…)

Michael B.

Aug 12 2015 at 9:54am

I wonder how much of the ineffectiveness of early detection is caused by the many months it can take to actually have a diagnosis confirmed and begin treatment due to long waiting periods.

KLO

Aug 12 2015 at 10:17am

Mortality rates are age-adjusted, so these stats do look at how long people live.

As with prostate cancer, the problem here is not so much that treatment does not work, but rather that overtreatment imposes mortality costs that are close to the benefits of treatment. If we could determine which cancers should be treated and which ones should not be treated, screening would produce better results.

BD

Aug 12 2015 at 10:32am

I agree with the direction of this post 100%, BUT you really need to clarify your first sentence.

It should read that this data “presents transparent statistical evidence against routine mammograms in women over 50“.

wd40

Aug 12 2015 at 10:37am

People with a history of cancer deaths in their family are more likely to die from cancer than those who do not have such a history. And people with a history of cancer deaths in their family are also more likely to undertake procedures to detect cancer (e.g., mammograms and PSA tests). Unless there were randomized controlled experiments or Gigerenzer was somehow able to accounted for such a possibility, I remain skeptical of Bryan’s argument.

Hazel Meade

Aug 12 2015 at 11:01am

Same objection as before.

The 21-in-100 number doesn’t tell us how old those 21 women were other than that they were “50+”. It tells us that they died within 10 years after the start of the study, but not how old they were at the start of the study or whether they had prior screening. It also doesn’t tells if the people who died were the *same* people who would have died absent screening. It could be that 3 fewer 50 year olds died and 3 more 80 year olds died. Maybe the negative effects of biopsies and screening are harder on older age groups, so past a certain age you want to stop bothering. But they could still be beneficial to younger age groups.

To make this point more broadly, lets say we made the age cohort 20+ years, and then said “what’s the utility of bike helmets?” And answered it with “Look 5% of all 20+ people are going to die within the next 10 years of some blunt trauma accident. Therefore bike helmets are useless.”

You would instantly wonder whether that 5% skewed younger or older in the two cases, wouldn’t you?

ThomasH

Aug 12 2015 at 2:29pm

Considering that judgments based on risk analysis are central to physicians’ practice, why is statistics not an important part of Medical school education. It’s more likely to be of long term benefit that many facts that will learned only to be forgotten.

John

Aug 12 2015 at 2:30pm

Given that some treatment “skews” the age of death, then given this data I would instantly wonder why no part of that “skew” extended past my time horizon–that is, if bike helmets really do reduce the risk of death in years 0-n, but have no effect on the risk of death in years 0-10, then they must necessarily increase the risk of death in years n-10. If the overall risk is identical but the risk in lower years is lower, the risk in other years must be correspondingly higher. Otherwise the overall risk will be lower!

With cancer, it’s possible to construct a model where we do see this, but treatment is still effective: there is some subset of people who are doomed to die of cancer by year 9, without exception, but screening and treatment means they die later. This model means it’s a good idea to get screened.

But that 9-year requirement is absurd (it requires that the risk of cancer be determined by the *year you join a study*, for god’s sake), and it’s crucial–if anyone gets cancer in year 9.5 and the treatment group has a reduced risk of death for the next 6 months, we’ll see a reduction in overall risk in the treatment group. We don’t see that.

Hazel Meade

Aug 13 2015 at 10:38am

@John – however in this case (50+) the “n” is infinity. It’s “until death”. But we don’t know the average life exepectancy of two groups. “n” could be larger in the screened group than in the unscreened group.

Vacslav

Aug 15 2015 at 3:16am

Gigerenzer analysis is surely incomplete: one can’t deduce whether this or that treatment is needed without supplying the definition of a “need”. One can’t make decisions based on purely statistical manipulations.

Population-centric cost-benefit analysis based on the expected balance of costs and benefits is also insufficient/incomplete because it ignores personal preferences and tastes.

Patient-centric analysis whereby individual costs and individual benefits and tastes and preferences are include is a bit more involved but offers a much richer decision-making framework than anything based on pure statistics or on the expected cost/benefit balances.

I studied breast cancer and prostate cancer screening from the patient-centric perspective in my Medical decision making: an introduction for medical professionals, scientists and health care policy makers

Comments are closed.