Welcome to the first installment of the EconLog Reading Club on Ancestry and Long-Run Growth. This week’s paper: Putterman, Louis, and David Weil. 2010. “Post-1500 Population Flows and the Long-Run Determinants of Economic Growth and Inequality.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 125(4): 1627-1682. The authors’ data is here.

Summary

Putterman and Weil start by noting that – at least by some measures – economic success is persistent over the centuries. Countries that were advanced in the distant past tend to be richer today. But should we think of countries as locations or peoples? Economists routinely do the former, but maybe they shouldn’t.

[T]he further back into the past one looks, the more the economic history of a given place tends to diverge from the economic history of the people who currently live there. For example, the territory that is now the United States was inhabited in 1500 largely by hunting, fishing, and horticultural communities with pre-iron technology, organized into relatively small, pre-state political units. In contrast, a large fraction of the current U.S. population is descended from people who in 1500 lived in settled agricultural societies with advanced metallurgy, organized into large states. The example of the United States also makes it clear that, because of migration, the long-historical background of the people living in a given country can be quite heterogeneous.

To surmount this problem, P&W laboriously construct a country-by-country matrix of ancestry:

We construct a matrix detailing the year-1500 origins of the current population of almost every country in the world. In addition to the quantity and timing of migration, the matrix also reflects differential population growth rates among native and immigrant population groups. The matrix can be used as a tool to adjust historical data to reflect the status in the year 1500 of the ancestors of a country’s current population. That is, we can convert any measure applicable to countries into a measure applicable to the ancestors of the people who now live in each country.

How could one even begin to construct such a matrix? Whenever possible, P&W use actual genetic data, then supplements genetics with history. What does their matrix look like?

The matrix has 165 rows, each for a present-day country, and 172 columns (the same 165 countries plus seven other source countries with current populations of less than one half million). Its entries are the proportion of long-term residents’ ancestors estimated to have lived in each source country in 1500. Each row sums to one. To give an example, the row for Malaysia has five nonzero entries, corresponding to the five source countries for the current Malaysian population: Malaysia (0.60), China (0.26), India (0.075), Indonesia (0.04) and the Philippines (0.025).

The resulting matrix exposes two basic facts.

1. Long-distance migration is rare. Most modern countries are almost entirely populated by the descendants of earlier inhabitants of the region.

2. Long-distance migration is bimodal. When countries aren’t almost entirely populated by the descendants of earlier inhabitants of the region, those earlier inhabitants usually have almost no descendants left in the country.

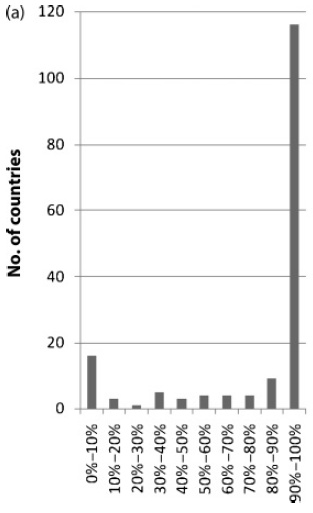

Check out the Distribution of Countries by Proportion of Ancestors from Own or Immediate Neighboring Country:

Here’s the Distribution of World Population by Proportion of Ancestors from Own or Immediate Neighboring Country:

Since migration history is bimodal, adjusting these measures for migration has a bimodal effect. Most countries are near the 45-degree line, but a few radically diverge. Here’s state history by location versus people:

Here’s agricultural history by location versus people:

After further checks, P&W switch gears to analyze how ancestry matters for current inequality. Punchline:

[T]he heterogeneity of a country’s population in terms of the early development of its ancestors as of 1500 is strongly correlated with income inequality. We also show that heterogeneity with respect to country of ancestry or with respect to the ancestral language does a better job than does current linguistic or ethnic heterogeneity in predicting income inequalities today.

This is an awesome paper. While I’m sure Putterman and Weil made countless judgment calls in constructing their migration matrix, I’d bet that if I re-did their work, my matrix would have at least a .8 correlation with theirs. This is a classic “obvious once you think about it” paper, because rich non-Eurasian countries are now largely inhabited by Eurasians. It is also a courageous paper. As far as I know, P&W were not tarred and feathered for racism, but they sure could have been. All political correctness aside, though, what is the reasonable way to interpret their results?

1. While Garett Jones sees ancestry research as very damaging to the case for free migration, Putterman and Weil acknowledge that most historical migration was anything but free. Indeed, demographic change largely reflects conquest, genocide, and slavery.

Conquest, colonialism, migration, slavery, and epidemic disease reshaped the world that existed before the era of European expansion. Over the last 500 years, there have been dramatic movements of people, institutions, cultures, and languages among the world’s major regions.

In other words, civilized migration – where people voluntarily move to a new country to peacefully improve their lives – is an extreme historical rarity. While this doesn’t prove that civilized migration has better long-run effects than conventionally brutal migration, it is plausible that dramatic long-run differences exist. Most obviously, civilized migration is an effective way to sincerely culturally “convert” people – and their children. Enslaving them, not so much.

2. P&W also detect a surprising benefit of ancestral heterogeneity:

We find that, holding constant the average level of early development, heterogeneity in early development raises current income, a finding that might indicate spillovers of growth-promoting traits among national origin groups.

3. While it doesn’t affect their case, P&W use extremely low populations for the New World in 1500. Is 1491 – and all the research upon which it builds – wrong? According to Wikipedia’s summary of current research, P&W are off by a factor of three or more.

4. The time discounting of state history is worrisome. Putterman and Weil use Chanda and Putterman’s 5% per half-century discount rate, but was this rate cherry-picked to make the results come out right?

5. On Twitter, Garett has been using the literature P&W jump-started to dissuade Western countries from admitting Syrian refugees. But by Putterman and Weil’s agricultural measure, Syrians (and every else in the Fertile Crescent) are the most awesome people on the planet. Here’s who the Syrians are, in case you’re curious:

The vast majority of Syria’s population is Arab, and is assumed to be indigenous to the country. There are also some Palestinian (2.8%) and Lebanese (0.5%) refugees living in the country (NE, WCD). Some Kurds (4%) have lived in the country for generations, but others (4%) came from Turkey in the early 20th century (LC, EV). The majority of Syria’s Armenians (0.2%) and Turks (0.3%) also came from Turkey during the first half of the 20th century as refugees (LC, EV,WCD). The Bedouin Arabs (7.4%) are believed to have emigrated from the interior of the Arabian peninsula between the 14th and 18th centuries; thus, the ancestors of about two-fifths of the Bedouins are treated as having lived in Saudi Arabia (3%), which constitutes the vast majority of the peninsula. There is also a small population of Azerbaijanis (0.7%) whose ancestors are assumed to have lived in present-day Azerbaijan (WCD).

Estimate:

Azerbaijan: 0.7%

Israel/Palestine: 2.8%

Lebanon: 0.5%

Saudi Arabia: 3%

Syria: 88.5%

Turkey: 4.5% (4% as ancestors of Kurds, 0.2% as ancestors of Armenians)

6. P&W are writing in a field where the effects of geography are well-established. They aim to show that ancestry matters even controlling for geography – and they succeed. But geographic variables remain highly potent. Who cares, when you can’t change geography? Well, you can’t change the geography of places, but you can change the geography of people. How? Migration!

Look at column (6) of their Table IV above. State history ranges from 0-1. Moving from the minimum to the maximum state history score predicts a +1.24 change in log GDP – an increase of about 350%. But you can get the same bonanza by moving 37 degrees away from the equator. If you go from a landlocked country to a non-landlocked country, a 20 degree move suffices.

Results for agriculture are similar. The variable ranges from 0-10.5. Moving from the minimum to the maximum agriculture score predicts a +1.61 change in log GDP – an increase of about 500%. You can get the same bonanza by moving 40 degrees away from the equator – or 26 degrees if you journey from a landlocked country to a non-landlocked country.

Taking P&W’s results literally, then, this is a radically pro-immigration paper. Let mankind move away from the tropics and toward the coasts, and the predicted net effect is cornucopian. This would be true even if all migrants’ ancestors were complete savages in 1500 AD. And if you look at P&W’s numbers, you’ll learn that even sub-Saharan Africans were well-above the minimum by 1500 AD, with state history scores around .2 and agriculture scores around 2. The implied long-run payoff from relocating humanity from poor countries to rich countries is plausibly even higher than the “double global GDP” estimate Michael Clemens popularized in “Trillion-Dollar Bills on the Sidewalk.”

7. P&W seems to imply a NIMBY result for immigration. Sure, migration enriches mankind, but doesn’t it reduce per capita GDP in receiving countries? Taken literally, their full results imply the opposite, but P&W are skeptical:

The coefficients also have the unpalatable property that a country’s predicted income can sometimes be raised by replacing high statehist people with low statehist people, because the decline in the average level of statehist will be more than balanced by the increase in the standard deviation. For example, the coefficients just discussed imply that combining populations with statehist of 1 and 0, the optimal mix is 86% statehist = 1 and 14% statehist = 0. A country with such a mix would be 41% richer than a country with 100% of the population having a statehist of 1…

Although our regression result reflects the fact that population heterogeneity has not detracted from economic development in the first group of countries, it seems best not to infer from it that “catch up” by homogeneous Old World countries would be speeded up by infusions of low statehist populations into existing high statehist countries.

Econometrics aside, per-capita GDP is a dreadful measure of national welfare when migration is high. As I often point out, immigration can enrich everyone in a country while reducing per-capita GDP. In any case, the NIMBY inference depends on the size of the receiving country. If Belgium doubles its production via migration, most of the extra production will spill over onto the rest of the world. But if the EU doubles its production via migration, most of the extra production will probably be enjoyed by people in the EU.

8. Overall, this is an amazingly edifying paper. If your main reaction is name-calling, you don’t belong in the world of ideas. If the paper showed that my crusade for open borders was misguided, I would just have to live with that unwelcome conclusion. But it shows nothing of the kind. Immigration critics looking for intellectual foundations will have to keep looking – or ignore half the paper’s results.

READER COMMENTS

E. Harding

Jan 27 2016 at 1:04am

“Most obviously, civilized migration is an effective way to sincerely culturally “convert” people – and their children. Enslaving them, not so much.”

-? The richest Black-majority countries are in the Caribbean, where all their ancestors were brought there as slaves.

“We find that, holding constant the average level of early development, heterogeneity in early development raises current income, a finding that might indicate spillovers of growth-promoting traits among national origin groups.”

-This is a correlation. There might be causation, but I doubt it. As in the case of the European countries with the most Muslims having the most scientific discoveries, some of this might be a product of a third factor behind both.

Postlibertarian

Jan 27 2016 at 9:45am

Also worth noting the paper dealt with the obvious issue of accidentally picking up migration simply as a proxy for European descendants:

Which also implies it isn’t just a European-ness issue, but actual migration itself has benefits.

Brad

Jan 27 2016 at 10:22am

So would the US be a little past the sweet spot WRT the optimal mix? At least as far as maximizing per capita GDP which admittedly is not the best target.

JayMan

Jan 27 2016 at 11:05am

Or the best economies are better at attracting immigrants from different places. In other words, you have the causation backwards.

Maybe that shows the limitations of going strictly by plain length of agricultural history.

They have? Even to the extent that geography has an effect, maybe there are a few links in between:

Genes, Climate, and Even More Maps of the American Nations

And this is why understanding the precise causation is important. It prevents you from saying silly things like that.

Only if you naively assume correlation = causation. But that’s par for the course for social science.

Tim Nutt

Jan 27 2016 at 11:38am

Quote from Caplan:

Now, for my comments. Bryan, this line of argument is so obtuse that I almost can’t believe you are making it in good faith. You observe the data, and acknowledge the historical fact that “civilized migration … is an extreme historical rarity.” Then, you skip ahead to the conclusion that “civilized migration (whatever that means) is an effective way…” At minimum, there are two crippling problems with your reasoning:

1. There are few if any historical examples, so there is no way to know

2. You flippantly assume that any current or future migration under Open Borders would somehow be “civilized.”

So, if I understand, All We Have To Do is figure out how to migrate people without causing “conquest, colonialism, slavery, and epidemic disease” for the first time in the history of the world, and *then* we can pick up that $1 trillion laying on the sidewalk?

Jeff

Jan 27 2016 at 3:22pm

I fully admit I had trouble following this post, due to some of the jargon as well as, you know, not having time or patience to read the whole paper, but what exactly is the mechanism for this, whereby just moving away from the equator increases GDP?

The closer you are to the equator, the longer your growing season is, and thus the more productive any agriculture you engage in should be, at least if you exclude desert areas like the Sahara and Western Australia. All other factors, equal, then, you’d expect equatorial peoples to be richer, given they probably have to devote less land and labor to agriculture. So how is it we observe the opposite? I’m worried the answer is simply that you’re overlooking the fact that geography impacts ancestry. For example, the long winters with little sunlight in northern Europe and Asia selected for lighter skin among the inhabitants there to counter Vitamin D deficiencies. Is it possible that when you look at geography impacting GDP, what you’re really looking at is the effect of climate on human evolution (ie, ancestry)? Or do I misread things?

Miguel Madeira

Jan 27 2016 at 5:16pm

It is more difficult to do regular labour under 40º C

[broken url removed–Econlib Ed.]

PD Shaw

Jan 27 2016 at 8:00pm

@Jeff, farming requires adequate sunlight, moisture and soil conditions. A lot of tropical soils are poor.

What I think the study is getting at is that there are certain types of institutions that develop depending upon agricultural practices. Locations where fruits and nuts are gathered from trees throughout the year develop different institutions from those where seasonal crops are sown. Locations where extensive irrigation is required develop differently from those where pastoralism predominates.

john hare

Jan 27 2016 at 8:32pm

This constant call for unlimited migration to solve income inequality has the same problem as calling for higher minimum wages to solve a similar problem. It assumes all people are the same. They’re not. Some people are more capable than others and always will be as noted in this post. Moving the ignorant and unmotivated to a better country doesn’t work any better than mandating a higher wage for them.

Immigrants are a blessing to themselves and their adopted nation only if they are the type that are willing and able to be such.

I think some of these authors should spend some time attempting to help people on the very bottom. People that borrow gas money when they spend more on lottery than fuel every week. People that quit jobs for little reason when they have no other income available. Entitlement, drugs, refusal to learn skills, alcohol, and on and on.

About 1 in 5 that I have worked with has gotten out. They were usually the easiest to work with and needed the least help.

Cliff

Jan 27 2016 at 9:39pm

So you are saying the paper indicates that open borders would be good because it does not refute earlier research that moving from certain geographic places to other geographic places improves productivity? If that is the baseline- and this research is NOT about geographic influences on productivity- then this paper moves you AWAY from that baseline and in a direction away from thinking that open borders is a good idea. Because what this paper says is that people are not fungible and who is migrating matters, a lot.

Mike

Jan 28 2016 at 4:50am

In looking at the open borders case, it might be useful to look at the impact on a high trust, liberal, welfare state such as Sweden. In 2010 Sweden was in 15th place in the UN Human Development Index HDI rankings. According to UN forecasts, Sweden will be #25 in 2015, and in 2030 on the 45th place. If you look at the employment outcomes for some groups entering, highlighted perhaps in the city of Malmo, it seems like a case study in open borders being a bad idea?

December

Jan 28 2016 at 7:28am

Did Bryan ever consider that the people inhabiting the countries closer to the equator have different average genetic composition which is driving the different agricultural or GDP stats? Maybe simply moving everyone north won’t help if the cause of the difference is more intrinsic to the person? Has Bryan ever seriously considered how potential difference in the distribution of genetic traits among human populations may effect his Open Borders philosophy?

Jeff

Jan 28 2016 at 9:01am

Yes, this is pretty much what I was trying to get at. Specifically when Bryan says the following:

Isn’t it likely that the effect is the same because these variables are essentially measuring the same thing? That is, folks whose ancestors originated from latitudes ~37 degrees from the equator have a certain mix of treats that led to A)earlier state histories and thus B)historically higher levels of GDP? Or am I missing something?

Emerson

Jan 28 2016 at 9:45am

This is all very interesting. But I observe an assumption in the discussion that seems to undermine the concept.

The assumption is that migration is compose of random individuals.

For example, the paper seems to imply that countries that became populated by Eurasians became more prosperous, and therefore Eurasian migration was a benefit.

But those Eurasions that migrated were not random Eurasians. They were a select group. Weak, apathetic, uninspired individuals do not migrate they stay put. This is true if the person was a conquesting soldier or voluntary individual

This is likely also true for migration by slavery. Slaves were culled from their population because of certain beneficial qualities.

To me the take home message from this is that selective migration-migration of individuals with beneficial qualities- no matter what the region of origin- is beneficial to the receiving region.

Perseus

Jan 28 2016 at 2:04pm

[Comment removed. Please consult our comment policies and check your email for explanation.–Econlib Ed.]

Phil

Jan 28 2016 at 3:16pm

what’s the point of a book club if you never answer any of the points brought up in the comments?

I get your bubble schtick, but honestly in spirit of the free exchange of ideas, you should break it and engage with you’re readers

—————

the paper?

honestly, the fact that papers like that exist make me really mad, not for any particular finding of the paper, but because of how hard it was to tease any significance out of it

what I could tell as the thesis of the meaning of the paper was something along the lines of “places that are rich now, are made of people who descended from people who were rich in 1500”

maybe that’s a dramatically oversimplified reading of the paper (I suspect it probably is), if that is, they should have made their point in far clearer English,

who are they writing for? why are they employed at one of the most prestigious universities in the country? Maybe I’m just too dumb to be involved in this discussion, but multiple standardized test scores tell me that if I’m too dumb to be part of this conversation, something on the order of 95-98% of the rest of population that wants to go to college is too

why as a society are we subsidizing discussions that no one can follow?

on the off chance that that’s not an overly

oversimplified reading of the paper, really, so what? what’s the significance? I could have/ would have guessed result w/o ever reading the paper

————————

why isn’t the matrix presented in a table at the end that inquiring minds could query?

why is this the work we let people in the most prestigious institutes for expanding human knowledge get away with?

—————–

I don’t follow how you went from the conclusions in the paper to your conclusion in this blog post at all, but tbf, I’m pretty sure I didn’t follow the conclusions of the paper

————–

“This is an awesome paper”, I’m going to disagree

side note – one thing I think you deserve a lot of credit for is that you writing is straight forward to parse, I do appreciate that

Mary

Jan 28 2016 at 11:54pm

I have always thought that the Pacific Islands would be a good test case of this theory. There were a range of migrations essentially coming into a similar polynesian world. For some islands (say New Zealand) the in-migration dominated the population. In others, say Samoa, it was a minority. In some cases it was British – others French – and others USA. There is even one German for a while. Finally there is also a significant migration from a non-European source – the Indians in Fiji.

If the result above holds true for this sub-group, it would strengthen the theory.

Bret Sikkink

Feb 1 2016 at 11:34am

@Phil and December: the literature you would want to see is largely from Galor, working with Moav (briefly cited in P&W 2010) as well as with Ashraf. Interesting work showing how genetic diversity forms a hump-shaped distribution when plotted against “walking distance from Ethiopia” due to settler effects (less diversity) and likelihood of encountering other groups (more diversity). When diversity is plotted against income, a similar if broad hump-shaped distribution is found.

Bret Sikkink

Feb 1 2016 at 11:47am

@Phil

why isn’t the matrix presented in a table at the end that inquiring minds could query?

Because it’s enormous. There’s a link in the PDF to Putterman’s website at Brown with the full 165×172 cell matrix.

what’s the significance? I could have/ would have guessed result w/o ever reading the paper

As Thomas Sargent says “economics is organized common sense”. You may have an intuition – even a correct one – about a given topic, but the research agenda is to verify which intuitions are correct and to what extent we can explore causation (why the intuition was correct).

why as a society are we subsidizing discussions that no one can follow?

I suppose you raise a valid point about the role in modern society of the researcher versus the popularizer. However, what is the popularizer to popularize if there’s no research going over most of our heads?

why is this the work we let people in the most prestigious institutes for expanding human knowledge get away with?

“Get away with”? This was a clearly written paper that referenced previous work, acknowledged the foundational ideas of the research agenda, posted their data, regression results, and matrix AND only had two equations. As Marshall said – “burn the maths”. P&W pushed the research forward through data collection (the matrix is available to others for their own theses) as well as tying the ideas of others together (Easterly, Acemoglu et al, Olsson and Hibbs, Galor and Moav, Hall and Jones, Diamond). This is a pretty awesome paper.

Bret Sikkink

Feb 1 2016 at 12:01pm

Almost forgot my own questions:

Putterman and Weil note AJR’s work on institutions and rightly for their line of questioning, disregard some of the analysis of that paper. For a finer-grained analysis in the future, however, it seems to me important to distinguish between different parts of “Eurasia” as the source region for migration, as well as how the migration occurred. That is, whether a country was founded by religious fanatics leaving England or conquered by professional soldiers from Castile seems relevant. Modelling the institutional quality of migrating populations seems like a next step in this research.

Additionally, can the African data be parsed more cleanly, given that there were eight major regions from which slaves were traded? Can we observe cultural or institutional differences in countries which experienced different types of African migration, or was the Middle Passage too disruptive an event to clearly distinguish between, say, Senegambian effects versus those from the Bight of Biafra?

David Weil

Feb 6 2016 at 10:04am

Dear Bryan,

Thanks for all the kind words about our paper. There is a lot going on in your critique as well as the comments. I won’t be able to address it all, but here are some thoughts:

1) The big issue that you want to address is what we learn about the economic effects of free immigration (a policy of open borders applied to the US today) from the PW analysis of historical migration. The PW finding is that the higher the fraction of the population of a country that is made of of people descended from early developing countries, the richer the country is, on average. From this, it seems like one could conclude that adding a lot of Syrian refugees to the US would make the US richer, since Syria was one of the earliest developers (using either of our measures).

I think drawing such a conclusion from our data is unwarranted, for several reasons.

First, the data just show correlations, not a structural relationship. For example, places with lots of descendants of Europeans (high state history) tend to be rich. That might be because the Europeans made them rich, but it might also be because Europeans went to places that had good characteristics. One could imagine an experiment of sending migrants randomly to different places in different proportions, then waiting 500 years to see how things came out, but that is not what happened.

Second, the environment in which migration would be taking place now is just completely different from migration historically. Most of the Africans who came to the New World did so as slaves on sailing ships; how could we learn from that experience what the economic effects of Africans coming as voluntary migrants on airplanes, into modern welfare states, would be?

Third, beyond the nature of migration, the whole world is very different. For example, when Europeans migrated to the Americas, they brought with them productive knowledge and ideas about the structure of society that could not have been transferred by any means other than migration. That is no longer the case.

All of this is not to say that open borders are a good or bad policy — simply that the historical experience examined by PW is not a good place to learn the answer.

2) I think that the issue of how geography matters is more complex than you let on. The correlations between latitude, being on the coast, and being landlocked with GDP per capita are all quite strong. But what do they mean? And in particular, do they mean that moving a lot of people away from the equator would make them richer? The Jeff Sachs view is that the answer is yes: the tropics are just a bad productive environment, bad disease environment, etc. By contrast the view of Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson is that characteristics of the topics led to the development of bad institutions there historically, and that it is these bad institutions that lead to bad outcomes today. Under this latter view, if we moved people from the tropics to temperate regions in such a manner that their institutions remained unchanged, then it would not make them richer at all.

3) One issue that you raise and is also followed up by some of the other commentators is what fraction of migration historically, or as measured in the PW data, was “civilized,” that is, people voluntarily moving countries to improve their lives. Non-civilized migration includes slavery and being a refugee. I think that this is a great question, and one that might be worth trying to collect data on. Before trying to guess an answer, we have to wrestle with a problem in the original paper, which is that the PW matrix doesn’t really measure migration, but rather ancestry. For example, the number of migrants who gave rise to the modern French Canadian population was very small, but a large number of Canadians have French ancestry. PW really know nothing at all about migrant flows, since we just look at the population of the world today.

So if we change the question to be what fraction of non-native ancestry is due to “civilized” migration, things are a little easier. We know that Africans in the New World are descended from non-voluntary migrants. Most of the European descended population is descended from civilized migrants. I don’t know the history well, but one should be able say something about the large populations with Indian and Chinese ancestry found outside those countries, and so on. Given the large number of “whites” in the Americas, I think that means that the majority of ancestry of non-natives is indeed due to civilized migration.

Comments are closed.