Great short piece by Michael Huemer, my favorite philosopher. Reprinted with his permission.

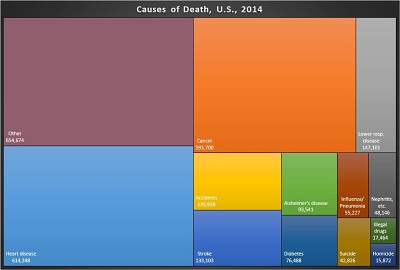

What’s

killing us? I made the following graph. I include the top ten causes of

death in the U.S., plus homicide and illegal drug overdoses, because

the latter two are actually discussed in political discourse.

Observations:

1. The top causes of death almost never appear in political discourse

or discussions of social problems. They’re almost all diseases, and

there is almost no debate about what should be done about them. This is

despite that they are killing vastly more people than even the most

destructive of the social problems that we do talk about. (Illegal drugs

account for 0.7% of the death rate; murder, about 0.6%.)

2. This

is not because there is nothing to be done about the leading causes of

death. Changes in diet, exercise, and other lifestyle changes can make

very large differences to your risk of heart disease, cancer, and other

major diseases, and this is well-known.

3. It’s also not because

it’s uncontroversial what we should do about them, or because everybody

already knows. The government could, for example, try to discourage

tobacco smoking, alcohol use, and overeating, and encourage exercise.

There are many ways this could be attempted. Perhaps the government

could spend more money on trying to cure the leading diseases. There

obviously are policies that could attempt to address these problems, and

it would certainly not be uncontroversial which ones, if any, should be

adopted. Those who support social engineering by the government might

be expected to be campaigning for the government to address the things

that are killing most of us.

4. Most of these leading killers are

themselves mainly caused by old age. If “Old Age” were a category, it

would be causing by far the majority of deaths. Again, it’s not the case

that nothing could be done about this. We could be doing much more

medical research on aging.

5. It’s also not that we just don’t

care about diseases. *Some* diseases are treated as political issues,

such that there are activists campaigning for more attention and more

money to cure them. There are AIDS activists, but there aren’t any

nephritis activists. There are breast cancer walks, but there aren’t any

colon cancer walks.

6. Hypothesis: We don’t much care about the

good of society. Refinement: Love of the social good is not the main

motivation for (i) political action, and (ii) political discourse. We

don’t talk about what’s good for society because we want to help our

fellow humans. We talk about society because we want to align ourselves

with a chosen group, to signal that alignment to others, and to tell a

story about who we are. There are AIDS activists because there are

people who want to express sympathy for gays, to align themselves

against conservatives, and thereby to express “who they are”. There are

no nephritis activists, because there’s no salient group you align

yourself with (kidney disease sufferers?) by advocating for nephritis

research, there’s no group you thereby align yourself *against*, and you

don’t tell any story about what kind of person you are.

In

conclusion, this sucks. Because we actually have real problems that

require attention. If we won’t pay attention to a problem just because

it kills a million people, but we need it also to invoke some

ideological feeling of righteousness, then the biggest problems will

continue to kill us. And by the way, the smaller problems that we

actually pay attention to probably won’t be solved either, because all

our ‘solutions’ will be designed to flatter us and express our

ideologies, rather than to actually solve the problems.

READER COMMENTS

Paul Miller

Oct 5 2017 at 2:45pm

Should we be looking at expected years lost? Unless we solve ageing in general (maybe good but less concrete) then it matters less if curing some of these diseases gets you months of low quality life than if a homicide is prevented that gits dozens of years of high quality life.

SBF

Oct 5 2017 at 3:14pm

I agree with Paul – we can do better than just counting bodies. Breast cancer gets a lot of attention in no small part because it leads to a lot of middle-aged deaths. Childhood cancers probably get even more attention on a per-fatality basis. Drunk driving got lots of political attention in the 1980s with the consequence of a massive reduction in deaths.

Our attention is also drawn to more preventable deaths, which is quite rational if attention is a limited resource.

Thus, we’re better utilitarians than Huemer makes us out to be.

There are, of course, other errors in our rationality besides the one Huemer implies. Complications from diabetes gets relatively little attention in part because the victims are mostly poor.

But more importantly, we aren’t pure materialist utilitarians. We care about justice, cosmic and personal, and we thus care more about homicides than suicides and are saddened/angered more by a 28-year-old mom dying of cancer than a 78-year-old mom dying of cancer.

Jeremy Bancroft Brown

Oct 5 2017 at 3:15pm

“Changes in diet, exercise, and other lifestyle changes can make very large differences to your risk of heart disease, cancer, and other major diseases, and this is well-known.”

I would score this as partly true in general but mostly untrue for cancer, other than cancers with obvious mutational signatures linked to, for example, smoking, drinking, grilled meats and sun exposure. There is an ongoing debate about this in the cancer field as described here: http://science.sciencemag.org/content/355/6331/1266.full

“There are AIDS activists because there are people who want to express sympathy for gays, to align themselves against conservatives, and thereby to express ‘who they are’.”

Does Huemer know anything about the history of the AIDS epidemic and AIDS activism?

“There aren’t any colon cancer walks.”

Well, no that isn’t true.

“The government could, for example, try to discourage tobacco smoking, alcohol use, and overeating, and encourage exercise. There are many ways this could be attempted. Perhaps the government could spend more money on trying to cure the leading diseases.”

Haha, the government does a fair bit of this already! But since we are on the subject, I would favor decreasing subsidies for meat production and increasing NIH funding.

Tom DeMeo

Oct 5 2017 at 3:23pm

One of the strangest posts I’ve ever read. Is this some form of satire?

Peter Gerdes

Oct 5 2017 at 3:48pm

While it is true that many people think that government intervention into behaviors that result in self-harm (smoking, eating fatty foods etc..) is net justified because of people’s limited rationality or externalities this doesn’t mean they don’t recognize the trade off at all.

Everyone recognizes that eating fatty food or smoking gives the individual doing it some amount of pleasure that offsets the harms of an early death. One might believe that human irrationality means that the pleasure isn’t fully worth the harm but no one doubts that the net harm here is less than the harm from being killed in a violent altercation.

More generally, if your chart was in terms of QALYs lost rather than causes of death I suspect it would provide a huge multiplier to violent deaths.

Still, I agree that overall most people aren’t good utilitarians. But whether the particular phenomena in this case is a result of the cause you described or the fact that we implicitly weigh deaths at the hands of another more seriously than self-inflicted risks isn’t clear.

I happen to agree with your claim about why we assert most claims but I just don’t think this provides a very compelling argument for it.

Philo

Oct 5 2017 at 3:49pm

“We talk about society because we want to align ourselves with a chosen group, to signal that alignment to others, and to tell a story about who we are.” Huemer throws out this hypothesis, but makes no attempt to support it.

Brian Buerke

Oct 5 2017 at 4:14pm

Based on Huemer’s chart (which is very hard to read, by the way–can’t we get a bigger version or get larger print?), it would appear that all the causes of death to humans are fairly small compared with legal abortion. Just saying….

Anthony

Oct 5 2017 at 8:34pm

I worry that there is a prima facie tension between the conclusion and point (2) used to justify it.

If in fact it is not uncontroversial what the solutions are to these problems, then that suggests that there are avenues to leverage the differences in potential solutions as tribal markers. Hence, there is reason to suppose that if politics is just tribalism, then we should still see people fighting over even these genuinely serious problems.

Response: The differences in solutions don’t lend themselves to effectively demarcating tribes. What are the potential solutions to nephritis? Drug A? Surgery B? Lifestyle change C? These don’t animate the tribal soul like the proposed solutions to terrorism do (war, immigration restrictions etc)

I believe there are likely good counter-responses. The tribal mind is surprisingly good at politicising even the most intrinsically non-political of fields. Nevertheless, I’m convinced of Huemer’s thesis.

gwern

Oct 5 2017 at 9:19pm

It wouldn’t. Violent deaths are far too rare and exotic to matter compared to things like heart disease, even if everyone who was murdered was murdered at birth. (Think about it: if 1% of people are murdered at an average age of, say, 25, and life expectancy is 75, then QALY-adjusting can’t more than triple the loss to the equivalent of 3%.)

If you don’t like Huemer’s post, the Global Burden of Disease project does in fact try to quantify all this and they provide a similar graph of DALYs lost in the USA: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/ (screenshot: https://i.imgur.com/kOYJUR4.png )

You see that all forms of violence combined in the US account for ~1% of DALYs lost, half that lost to suicide and a quarter to drugs.

In general, Huemer’s assertions are correct: heart disease, smoking, diabetes, anxiety, depression, and back+neck problems are the leading causes of DALY loss and are hardly discussed or considered problems. Smoking and Alzheimers and road injuries get somewhat closer to proportional attention but still not great. Stuff like kidney disease or bipolar disorder or congenital birth defects or falls aren’t even on the agenda. (Although he underestimates drug abuse which actually is one of the larger individual categories of problems.)

Incidentally, as far as childhood cancer goes: you have to look pretty hard to even spot the ‘leukemia’ hiding in the corner of the <20yo DALY-loss chart rather than note car accidents, birth defects, skin problems, depression, suicide, or misbehavior https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

[broken html less-than sign fixed; shortened urls replaced with full url–Econlib Ed.]

bill

Oct 5 2017 at 9:21pm

Colon cancer walk in Philly was on Sept 9.

John Salvatier

Oct 5 2017 at 10:21pm

The graph is too small to read

Rebes

Oct 5 2017 at 10:55pm

Isn’t this analysis misleading?

Ultimately, everybody dies of something. If we perceive an issue that needs to be addressed, it should be causes of premature death, not simply causes of death. What would the incomprehensible chart look like if it presented data on premature death, say, death at an age earlier than ___.

Kevin Erdmann

Oct 5 2017 at 11:10pm

Just lifting the ban on being compensated for giving up a kidney would save more lives than all the homicides take.

ChrisA

Oct 6 2017 at 1:41am

News flash – philosopher notices that people’s moral reactions are not consistent with his theory on what they should be.

Once again, there is no consistent moral theory that will satisfy all (or perhaps any) moral instincts. You are inevitably going to get a “repugnant reaction” should you try to actually apply your moral theory in real life. For instance in this case arguing for governments to restrict access to fatty foods for overall health reasons may increase overall life span, but it is surely going to annoy those who prefer the freedom to eat what they want.

There is no answer to this problem, no tweaking of a particular theory (lets say utilitarianism somehow combined with libertarianism) that will solve it. Its like this difference between having a theory of love, and actually falling in love. The two are only going to accidentally the same.

The best thing that moral philosophers can do is acknowledge this fact and argue that all you do in morality is follow your instincts, because that is what you are going to do anyway. (Example – you have to smother baby Hitler to avoid the Holocaust – I couldn’t smother a baby no matter what the positive utilitarian consequences would be). Oh and don’t try to argue that others should follow your moral instincts, it won’t work.

Finally politics should be about solving coordination problems that appeal to majorities of the population (like cleaning up litter), not imposing moral structures or righting perceived wrongs.

Henry

Oct 6 2017 at 4:33am

Snarky theory – Huemer doesn’t really care about those issues either (as a radical libertarian, I don’t see him advocating for say, health paternalism). He mainly cares about getting a dig in at what he perceives to be hypocritical liberals and their supposed virtue signalling.

I do actually agree that there are some irrationalities around what we prioritise. I’m just adverse to the self-congratulatory “this is because my political opponents are biased” explanations.

Roger Sweeny

Oct 6 2017 at 7:25am

3. Various governments already “try to discourage tobacco smoking, alcohol use, and overeating, and encourage exercise.” The problem is that it’s damn hard. There are powerful reasons people smoke, drink, overeat, and don’t move much.

I just finished Philip Guyenet’s The Hungry Brain, which argues pretty convincingly that there’s an “evolutionary mismatch” between our neurobiological systems that regulate eating and the availability and “palatability” of food today.

But the logic of the book is that if we really wanted to “combat obesity”, we would have to prohibit all advertising of food, even all pictures of food, put warning labels on food packaging (say, pictures of 400 pounders on ice cream containers and in big letters, “DO YOU WANT TO LOOK LIKE THIS?), and maybe simply prohibit the production, sale, and use of “hyperpalatable” food (potato chips, ice cream, etc.). That’s just not going to work.

P.S. As everyone in Pharma knows, no drug in the USA can be sold unless the FDA finds it “safe and effective” in combating a disease. According to the FDA, “aging” is not a disease so it will not even look at applications for a drug that slowed aging. That may have something to do with the lack of research.

Ricardo

Oct 6 2017 at 10:13am

@Kevin — as I’m sure you know, legalizing organ sale would be just the way to prompt the sort of mood affiliation response that Huemer decries… opponents would be “for the poor” and “against the heartless profiteering capitalists.” (But I am in favor of legalization of organ sales… and not just because I have kidney disease…)

Jacob Egner

Oct 6 2017 at 4:34pm

I agree with John Salvatier, the graph is unfortunately too small to comfortably read.

gwern: Thanks for your very illuminating figures and points.

Snippet from the post:

This sentence scores a 9.8 on the Hanson Scale. Certainly the most Hansonian sentence I’ve read in the last 72 hours, which is to say I enjoyed it and thought well of the author for recognizing such patterns in human society.

Aaron

Oct 6 2017 at 9:36pm

News Headline: Local Philosopher says people eat too much junk food.

Brad D

Oct 7 2017 at 10:08am

[Comment removed. Please consult our comment policies and check your email for explanation.–Econlib Ed.]

Jack PQ

Oct 7 2017 at 1:42pm

Would it be possible to embed the figure so it can be zoomed in please? Currently resolution is too low to read. thanks.

Seth Green

Oct 9 2017 at 3:43pm

Bryan and/or Michael, would you mind posting a link to the data for your graph, the code you used to produce it, or a link to a lossless version? I can’t read this one. Thanks!

Sam

Oct 11 2017 at 10:48pm

You make an unstated assumption: death is bad. But we have too many humans on Earth, and within the U.S. Therefore I do not want a government that makes the same assumption you do.

Comments are closed.